Editor’s note: EWTN will premier the heroic life of Venerable Aloysius Schwartz in its documentary series, They Might Be Saints tonight at 5:30 pm ET. Lear more by clicking here.

CHALCO, Mexico – The happy roar breathed to life in a gentle southern Korean peninsula town, then moved south across the East China Sea into the archipelago of the Philippines. From there, the happy noise traveled west to the dry plains of Tanzania. And as you read this sentence, the party is in full force in Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Venerable Fr. Aloysius Schwartz is dead. And more than 20,000 children—in 17 Catholic Boystowns and Girlstowns spread across the world—couldn’t be happier.

These children rejoice because they are the Lazarus’s pulled from the tomb by the Sisters of Mary, a religious order founded by Fr. Al in 1964. Each of the students—and more than 170,000 graduates in total—take time each March 16 to recall what all good shepherds must do; they lead the way. Fr. Al, a holy American priest on the path to canonization, is in heaven; he has led the way yet again.

“It’s a strange thought, but it is so true—these children who were one the poorest in the world are now the richest,” said Fr. Dan Leary, the chaplain for the Sisters of Mary and the children. “And they are grateful that Fr. Al suffered, died, and went to heaven because just as he came to them in their poverty and brought them into the villas, he goes before them again to heaven to show them the way to everlasting life with God.

“He is as much their spiritual father now as he was when he was alive. Every single child—so many of whom have lost their own earthly fathers—are aware they have a spiritual father in Fr. Al. They know he will never leave them. He is as close to them now as their next breath.”

On March 16, 1992, Fr. Al breathed his last, after three years of suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Lou Gehrig’s Disease. This suffering was no accident. “Our role is to mingle our blood with the blood of Christ”, he once said, “and to shed our blood with that of Christ to the poor. … The way we serve is to have a constant crown of thorns.”

But today is a day of celebration for the man on the path to sainthood in the Catholic Church. Teenagers are spending their time in the annual “Father Al Olympics,” where thousands throughout the globe compete against one another in basketball, handball, soccer, swimming, and even chess. These are not gentle affairs; high school athletic teams from Fr. Al’s Boystowns and Girlstowns regularly win national championships.

These Boystowns and Girlstowns have produced professional athletes, orchestral musicians, Toyota executives, restaurant owners, teachers, attorneys, engineers, architects, priests, nuns, and countless other professions. Each of these students and graduates shares one thing in common; they once grew up in stark poverty. Many would be dead if Fr. Al hadn’t reached for them.

Schwartz—or Fr. Al, as everyone called him—had a mission to nourish the souls of the humiliated, neglected, and most poverty-stricken people in the world. He tended to orphans, to lepers, to outcasts, to unwed mothers, to the developmentally disabled, and all others on the margins. He built hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, homeless centers, houses for the disabled and for unwed mothers. The work eventually expanded to the Philippines in the 1980s. When he opened the doors to the Mexican poor in 1991, his body was fading away in the grip of ALS.

As I was writing my book The Priests We Need to Save the Church in 2019, I found no one—priest or layperson—like Washington D.C.-born Fr. Al. In my research, I read the lives of several priestly paragons, including Damien the Leper, Vincent de Paul, John Bosco, Maximilian Kolbe, and John Vianney. Learning about Fr. Al’s life, though, was like finding traces of a white whale on the open sea, broad and mighty and flabbergasting. Perhaps no priest in the history of the world did as much as he did for the orphaned and tormented child. “People say that Saint Vincent de Paul was the great apostle of charity and that Fr. Al Schwartz based his entire missionary life on his”, noted Monsignor James Golasinski, who worked alongside Fr. Al for ten years in the Far East. “But I’ve told people that Monsignor Aloysius Schwartz accomplished more than Saint Vincent de Paul. What Fr. Al managed to do is beyond the pale. I was there, and I saw what happened.”

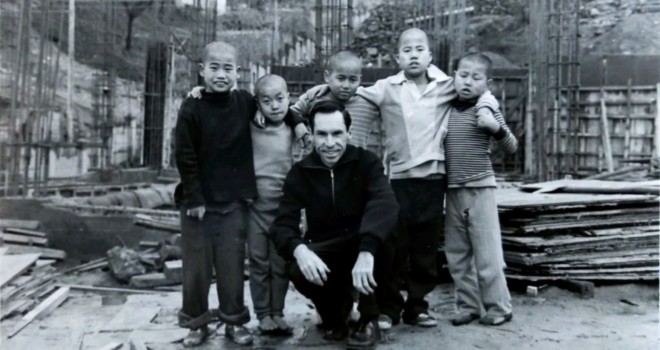

After ordination in 1957, Schwartz raised his hand to be sent to the saddest place in the world: South Korea after the Korean War. On the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, he stepped off the train in Seoul as a fresh-faced priest and found himself in a dystopian novel. Squatters with blank stares picked through hills of garbage. Paper-fleshed orphans lay on the streets like leftover war landmines. The scene haunted him. So he reached down to lift up one child, then another. And within a few years, he had changed the course of Korean history, and many in the southern peninsula saw him as Atlas. Yet he prayed to be unknown. The reason you don’t know about him is that he didn’t want you to know.

Had Saint Teresa of Calcutta never come under the gaze of biographer Malcolm Muggeridge, she likely would have remained in obscurity, as Schwartz has. Mother Teresa and Father Al esteemed each other’s work from afar, though their styles were different, and occasionally they crossed paths. At one of their encounters, Fr. Al told Mother Teresa he wanted to buy her some washing machines. The saint squinted her eyes. He explained: “Your sisters shouldn’t be wasting their time hand-washing their saris. The world already knows their humility; they should stay in the streets, working.” Brash as it was, he meant it, and she understood. This was his manner, and he got away with it because he seasoned his bluntness with a wink. “He was the boldest man I ever knew”, claimed Monsignor Golasinski. “He feared nothing.” By turns, Schwartz was hunted by American bishops, Korean bishops, a murderous kingpin, a gang of lepers, and his own seminary rector. And each time, he passed right through their midst. “I think he was not even afraid of God,” Filipino Bishop Socrates Villegas said, “because perfect love casts out all fear …. He was only afraid of one thing. My dear children, he was only afraid of sin.”

But the bishop wasn’t entirely right. Fr. Al also feared disappointing his Queen. One evening in 1957, Al Schwartz, still a young seminarian, knelt down in a countryside chapel in Banneux in weather-miserable northern Belgium. Twenty-four years earlier, the Blessed Mother had—it was said—appeared there, calling herself the Virgin of the Poor. That night in her chapel, Al consecrated his life to Mary, vowing to spend the remainder of his days surrendering his will and comforts to serve her and her poor. Thereafter, miracles came, one after the other. He would found an order in her name—the Sisters of Mary of Banneux—and in 1992 he would fade away while calling out her name. “I would be happy with a hole in the ground”, he quipped, “and a little plaque saying something like this, ‘Here lies Al Schwartz. He tried his best for Jesus.’ That’s it… My apostolate is hers and I would like to be buried at her feet and say, that all praise, honor, and glory for anything good accomplished in my life goes to her and to her alone.

✠