Augustus John Tolton, the second of three children, was born into slavery on April 1, 1854, in Brush Creek, Missouri. His baptismal record reads, in part, “A colored child. . . . Property of Stephen Eliot.” His mother, Martha Jane Chisley, was given as a wedding gift to the Eliot family, on whose plantation she met and married Augustus’s father, Peter Paul Tolton. When Augustus was seven years old, his father died in the Civil War, fighting for the belief that all men, including blacks, are equal and should have the same rights and privileges as whites.

That same year, the remaining members of the Tolton family escaped from slavery via the Underground Railroad to Quincy, Illinois. Shortly after their arrival, Augustus and his siblings were enrolled at St. Boniface Catholic School, where they were taunted with harsh, racialized insults by classmates. Many parents threatened to remove their children and withhold financial support from the parish. The pressure from the white parents and parishioners soon became too great for the family to bear. Mrs. Tolton withdrew the children from school.

Augustus found work in a tobacco factory and helped support his family. After work, a small group of dedicated nuns and priests taught him to read and write in both English and German, which fostered his love for learning. One of these priests was Fr. Peter McGirr, pastor of the nearby St. Peter’s parish and school. He admired Augustus and recognized his abilities and was convinced that Augustus should receive a Catholic education, and so he invited him to attend St. Peter’s school. Aware of Augustus’s experience at his previous school, Fr. McGirr “prepared himself for any unpleasantness or trouble that might arise” and “redoubled his resolution not to be intimidated or dissuaded by the parishioners.”

With the help of the School Sisters of Notre Dame, who promised to teach Augustus when others refused, Fr. McGirr defied the parishioners and admitted Augustus, who attended school during the winter months, when the tobacco factory was closed.

Augustus became an altar server and quickly memorized the Latin prayers for Mass. At the age of sixteen, he received his first Holy Communion, and, during Fr. McGirr’s homily, in which he explained the meaning of the Holy Eucharist and the Sacrifice of the Mass, Augustus’s heart, in his own words, “leapt with a strange exhilaration.” It was on that day that young Augustus envisioned himself becoming a priest.

Realizing the depth of Augustus’s “genuine faith and integrity,” Fr. McGirr became convinced that the boy was meant for the priesthood, and he encouraged and nurtured his fledgling vocation. Augustus received the sacrament of Confirmation at age eighteen and graduated “with distinction” from St. Peter’s. It was the summer of 1872.

The Struggle for Acceptance

Soon after commencement, Fr. McGirr, with the aid of another priest, helped Augustus to apply to the Franciscan Order — where he was met with the first of many rejections. Undaunted, Fr. McGirr secured the promise of the diocesan bishop to fund Augustus’s seminary training if a seminary could be found that would take him. Fr. McGirr wrote to every seminary in the United States, and all of them rejected a Negro candidate.

This article is adapted from the intro to Father Augustus Tolton.

There was some hope, however, that at least one religious community would be open to a black seminarian. The St. Joseph Society for Foreign Missions (today known as the Josephites) established a mission at the Church of St. Francis Xavier in Baltimore expressly to evangelize freed blacks. In 1875, another priest who supported Augustus’s cause, Fr. Theodore Wegmann, contacted the Josephites about him. They informed Fr. Wegmann that they had no seminary in the United States and suggested that Augustus become a catechist; then, if accepted by their order in London, he could become a missionary priest in Borneo.

While enthused by the prospect of becoming a missionary priest, Augustus was beset by a series of setbacks, most notably the reassignment of several priests who were overseeing his academic and spiritual formation. This forced the Tolton family to relocate to Missouri, where the brilliant yet troubled Fr. Patrick Dolan took over Augustus’s studies. An alcoholic, Fr. Dolan neglected Augustus’s studies and informed him that, in his parish, only white boys were allowed to be acolytes at Mass.

Augustus took a job in a saloon, where he experienced firsthand the degradation of humanity among the men and women who “sacrificed their dignity to wallow [in] the stench of reeking bodies, alcoholic fumes and stale tobacco [that] pervaded the entire atmosphere.” Not making any progress toward the priesthood in Missouri, the Toltons moved back to Quincy.

Augustus was more determined than ever to be a priest. He found a job making horse collars, and Fr. Francis Reinhart, chaplain at St. Mary’s Hospital and assistant pastor at St. Boniface Church, took over his studies. Augustus next took a job in a soda factory for twelve dollars a week, which allowed him more time for study. Fr. Reinhart was reassigned in 1878, and, with the help of yet another sympathetic, supportive priest, Augustus registered at St. Francis Solanus College (now Quincy University), where he studied mathematics, science, and literature.

Encouraged and assisted by Franciscan Fr. Michael Richardt and Sister Herlinde Sick, Augustus began teaching Sunday school to Negro children. Sister Hemesath relates the results:

The silent, unobtrusive activity of Augustine Tolton was largely responsible for the apostolate to the blacks of Quincy. Both he and his mother were tireless in their efforts to reinstate members of their race in the Church and to encourage others to study the Catholic religion. . . . Augustine understood the problems and temptations of his race; he knew the underlying causes of weakness and degradation in which many were steeped. With all his heart he deplored the lack of spiritual guidance and opportunities for rehabilitation open to untutored and downtrodden blacks. Yet, he could understand why some white people were hostile, why many Catholics were indifferent, and why those in positions of authority in the Church sometimes vacillated.

Priesthood at Last!

In 1879, at the age of twenty-five, Augustus learned that the local bishop’s attempt to have him admitted to the seminary in Rome had been unsuccessful. At the time, the Vatican accepted candidates for the priesthood from countries without seminaries in order to prepare them for a life of missionary work. But Rome was naively optimistic about the Catholic Church in the United States, believing that Augustus could and should be trained in America, where the freed slaves needed priests.

The Vatican did not fully appreciate that, although America had many seminaries for a nation still considered mission territory, the Church in America had consistently failed to live up to the tenets of Her own creed and gospel. The bishop recommended that Augustus wait a few more years until the Josephites could open a seminary in Baltimore.

The news devastated the aspiring priest. “Augustine referred to this period in his life as a season of annealing. It was a year during which his faith was repeatedly subjected to the severest test, a year during which days and weeks of disillusionment and frustration at times drove him to the brink” of total despair — where his whole being seemed to be engulfed in impenetrable darkness. But it was also an opportunity for gaining moral strength and courage that would prepare him well for life as the nation’s first black priest.

In a last-ditch effort, Fr. Richardt wrote to the superior general of the Franciscan Order in Rome to make an appeal on Augustus’s behalf. He “referred to Augustine as a reverent acolyte, a devoted son, a faithful worker, a diligent student, and a zealous lay apostle.” The report included a detailed description of Augustus’s theological and spiritual formation to date, as well as an accurate account of the reasons Augustus was rejected by the seminaries in the United States.

Fr. Richardt’s plan worked, and Augustus was accepted to the Urbanum Collegium de Propaganda Fide in Rome. He departed on February 15, 1880, and arrived March 12, the feast of Pope Gregory the Great, “one of the most determined enemies of slavery who ever sat in the Chair of Peter.”

Augustus was welcomed unconditionally and sincerely by the Vatican, not only as a seminarian, but also as a full member of the Church.

Augustus thrived in the Eternal City, where his priestly vocation was nurtured and his gifts and talents were recognized, prompting the prefect of the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide to note what the American Church failed to appreciate: “Fr. Tolton is a good priest, reliable, worthy, and capable. . . . He is deeply spiritual and dedicated.”

After being ordained to the priesthood on April 24, 1886, Fr. Augustus Tolton toured England and Europe. He celebrated his first Mass in the United States for the School Sisters of Notre Dame. To this day, a plaque in the chapel of St. Mary’s Hospital in Hoboken, New Jersey, reads: “The first Mass in the United States by the first Afro-American priest and ex-slave was celebrated on Wednesday, July 7, 1886.”

Fr. Tolton then celebrated his first solemn High Mass at St. Benedict the Moor Church, a black parish in New York City, on July 11, 1886, before a massive congregation. One week later, Fr. Tolton returned to Quincy, where he was soon installed as pastor of St. Joseph’s parish, which served the black Catholics of Quincy.

Back in Quincy

He taught Bible history and catechism and instructed those seeking to enter the Church; he conducted counseling sessions, made home visits to the aged and sick, and recruited new parishioners. Fr. Tolton welcomed all, black and white, into his parish. The white members of his congregation were generous with their financial and moral support for his work. Those who heard Fr. Tolton sensed the presence of the living Christ in him, and he developed a reputation as an outstanding preacher. Every Sunday, Mass at St. Joseph’s was filled to capacity.

Despite these advances, the parish suffered instability caused by dire poverty and moral corruption, which had devastating effects on the black community. In addition, there were deliberate, systematic, and sustained attempts by Protestant denominations and “secret societies” to lure blacks away from the Catholic Church.

In one of the most painful episodes of Fr. Tolton’s priesthood, he discovered that a white priest, Fr. Michael Weiss, had openly referred to him as the “nigger priest.” Furthermore, Fr. Weiss insisted that white worshipers’ contributions to St. Joseph’s belonged to their own (white) parishes and that attendance at the black church was not valid for white Catholics. Despite their affection for Fr. Tolton, many white parishioners left St. Joseph’s.

When Fr. Tolton’s charitable attempts to reach an understanding with Fr. Weiss failed, Bishop James Ryan — who was a friend of Fr. Weiss — told him to minister to blacks only. The situation became so intolerable that Fr. Tolton appealed to Rome, requesting a transfer to another diocese. After a lengthy investigation, the Vatican approved his request. On December 7, 1889, Fr. Tolton received permission to transfer to the Archdiocese of Chicago after making an inquiry to Archbishop Patrick Feehan, who was thrilled to have Fr. Tolton among his priests. He left Quincy on December 19, believing he had been an utter disappointment to black Catholics there, and with the words “total failure,” which had been suggested by some members of the white clergy, still ringing in his ears.

Chicago & The Last Years

In Chicago, Fr. Tolton was appointed pastor of St. Augustine’s Church, which was located in the basement of St. Mary’s and comprised blacks who were either barred from white parishes, were newcomers from the South, or were considering the Catholic Faith. Archbishop Feehan had complete confidence in Fr. Tolton, giving him full jurisdiction of all Negroes in Chicago.

However, as in Quincy, Fr. Tolton faced pressures both external and internal to the black community that were caused by segregation. The external factors included the racist attitudes of white priests and parishioners, and the aggressive proselytization of black Catholics by Protestant ministers. The internal factors included rampant poverty, substance abuse, economic instability, and moral squalor.

As a result, Fr. Tolton received permission from Archbishop Feehan to open a temporary storefront mission (St. Monica Chapel) in the heart of Chicago’s black district. Archbishop Feehan purchased the land and instructed Fr. Tolton to begin plans to build a real church. This required significant capital; the still-young priest knew this would be a daunting task given the neighborhood’s prevailing economic circumstances. Most of the black population in the neighborhood was unemployed, transient, indolent, or isolated.

With the help of parishioners, Fr. Tolton embarked on an aggressive fund-raising campaign, to which he contributed from revenues received from speaking engagements throughout the United States. He even appealed to Katharine Drexel, the famed educator who would later be canonized, for funds to build St. Monica’s. He raised enough for construction to begin in 1891.

In 1893, due to lack of funding, construction was halted and a temporary roof was installed, allowing the lower level of the church to be used for Mass and religious education. Fr. Augustus lived with his mother in the rectory behind the church, where she served as housekeeper and sacristan. Sadly, St. Monica’s was never completed, and the parish was closed permanently in 1945.

Since moving to Chicago, Fr. Tolton had battled illness, and he grew weaker as he ignored his health and ministered unselfishly to the black community, helping to meet both their corporal and spiritual needs. The awesome responsibility for and obligation to the black Catholic community that Fr. Augustus carried on his shoulders and in his heart took its weighty toll, and on July 9, 1897, Fr. Augustus John Tolton died in Chicago of complications from heat stroke and uremia. He was forty-three years old. Fr. Tolton returned to Quincy, Illinois, one last time: to be buried in the priest’s cemetery at St. Peter’s.

✠

This article is adapted from the introduction to Father Augustus Tolton: The Slave Who Became the First African-American Priest. It is available as a paperback or ebook from Sophia Institute Press.

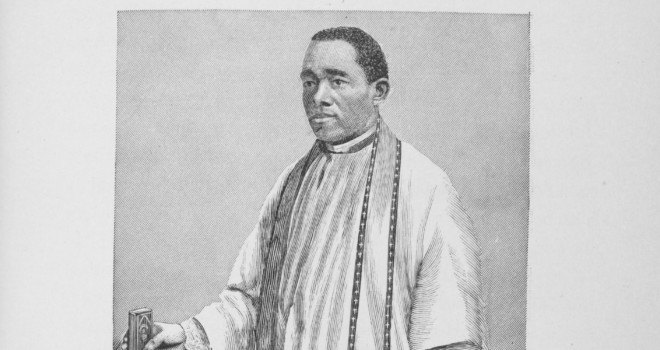

image: “Augustus Tolton” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1887.