“With nothing to consider they forget my name.”

~ The Ting Tings

In Saturday’s Gospel, St. Luke narrates his version of a familiar story:

“Jesus saw a tax collector named Levi sitting at the customs post. He said to him, ‘Follow me.’ And leaving everything behind, he got up and followed him” (Lk 5.27-28).

Mark’s version is essentially the same as Luke’s, and yet when we hear or read either one, we automatically substitute the name “Matthew” for “Levi” — which is what St. Matthew did in his telling of this watershed moment.

Some Bible scholars speculate that the Levi version is original, and that the author of the first Gospel substituted Matthew’s name to bestow an apostolic lineage on this sinner so singled out by the Lord. But tradition holds otherwise, and I like John Delaney’s summation on the discrepancy. “Called Levi (though this may have been merely a tribal designation – that is, Matthew the Levite),” Delaney writes in his Dictionary of Saints, “he was…a publican tax collector at Carpharnaum when Christ called him to follow him, and he became one of the twelve apostles.”

In other words, Matthew was the official’s name, but Levi marked out his heritage and family — what we might call first name and surname today.

There’s a parallel in how we identify ourselves as followers of Jesus. When asked our religion, we’ll typically refer to ourselves as “Roman Catholics” or just “Catholics,” but, if pressed, especially in conversations with evangelicals or fundamentalists, we might go on to specify that we’re Catholic Christians – that is, while we’re named “Catholic,” our religious family is already (for the information of those intent on proselytizing us) “Christian.”

St. Pacian of Barcelona would demur.

St. Pacian of Barcelona

St. Pacian was a fourth century bishop and church father whose virtues were noted by none other than St. Jerome. Pacian was a strong advocate for Christian unity and papal authority. In particular, as his few extant writings demonstrate, he was an ardent opponent of the Novatian heresy which stipulated that lapsed believers could never be reconciled with the Church. Pacian sided with Pope Cornelius who maintained that contrite apostates could be readmitted to full communion after a period of penance.

Pacian is most famous for a single Latin epigram that appears in one of his letters to a Novatian schismatic:

And yet, my brother, be not troubled; Christian is my name, but Catholic my surname [Christianus mihi nomen est, catholicus vero cognomen]. The former gives me a name, the latter distinguishes me. By the one I am approved; by the other I am but marked.

Here, the good bishop draws a line in the sand: Anybody can call himself a Christian – it is, after all, just a nickname, a label, a tag – but only Catholics can lay claim to a direct association with the Church established by Christ. “In her subsists the fullness of Christ’s body united with its head,” the Catechism states. “The Church was, in this fundamental sense, catholic on the day of Pentecost and will always be so until the day of the Parousia” (CCC 830).

This was true in the early church as well. At first, those who accepted the Gospel were simply referred to as “disciples” of Jesus or followers of The Way. Yet we know from St. Paul that there were divisions even among these original believers. Here’s what he wrote to the Corinthians:

It has been reported to me by Chlo′e’s people that there is quarreling among you, my brethren. What I mean is that each one of you says, “I belong to Paul,” or “I belong to Apol′los,” or “I belong to Cephas,” or “I belong to Christ.” Is Christ divided? Was Paul crucified for you? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul?

Paul’s insistence that there can’t be parties within the church echoes Jesus’ prayer, on the eve of his crucifixion, that all his disciples remain united. “I do not pray for these only, but also for those who believe in me through their word,” he prayed, “that they may all be one…so that the world may believe that thou hast sent me” (Jn 17.20-21).

Of course, the label “Christian” does have an ancient provenance and a legitimate biblical pedigree. Luke testifies in Acts that the term was applied to the disciples in the city of Antioch around the same time that Paul himself was ministering there. Even so, the tendency of the church to fragment was apparently tough to contain, and each of those fragments, no matter how heterodox or schismatic, stuck to the Christian appellation like glue.

So it was that the church of authentic apostolic origins adopted the name “catholic” to differentiate herself from imposters and interlopers. “Where the bishop is present, there let the congregation gather,” writes St. Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans around the year 107, “just as where Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church.” It’s the earliest recorded application of the word to the corporate body of Christ-followers, and the fact that Ignatius (himself from Antioch) assumes his readers know it indicates that it had already been long in use.

But why “catholic?” The word means “universal” in Greek, and so it squared with the early explosive spread of the true Gospel of Jesus throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond, despite the deviations of false gospel campaigners. But there’s more. “The term was already understood even then to be an especially fitting name because the Catholic Church was for everyone,” writes Kenneth Whitehead, “not just for adepts, enthusiasts or the specially initiated who might have been attracted to her.”

Nor just for saints, either. That’s the beauty of St. Pacian’s battle against Novatianism: the good bishop was committed to preserving the Catholic Church’s catholicity by welcoming back repentant infidels, schismatics, and sell-outs, no question. That’s in line with the latter part of today’s Gospel – the part where Jesus dresses down the Pharisees and scribes who’d been murmuring about the rabbi’s hobnobbing with miscreants. “Jesus said to them in reply, ‘Those who are healthy do not need a physician, but the sick do. I have not come to call the righteous to repentance but sinners’” (Lk 5.31-32).

March 9th is St. Placian’s feast. Take the opportunity to reflect on your faith names and their implications, give thanks to God that you’re part of the Catholic clan — sinners and saints alike — and resolve to spend your Lent responding to the Physician’s invitation to healing and wholeness.

St. Placian, pray for us!

✠

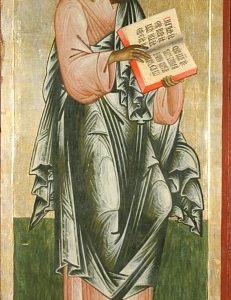

image: Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Saint Eulalia by Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]