For Christians it’s hard to imagine there not being

a Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, but why are there three persons?

Why the Question Matters

The answer is not an easy one, so our first order of business is explaining why it is worth looking for it. First, our faith seeks understanding. As Aristotle said, “all men long to know” (The Metaphysics). It’s not just our faith that seeks understanding, however. It is our love too. When you love someone, you want to know everything about them. Most importantly, you want to know what makes them who they are. Our love for God calls us to know Him ever more deeply.

A second reason is that such understanding has the potential to help us in explaining our faith to others. Third, peering deeper into the mystery of God cannot help but stir our wonder and awe at the divine majesty. Theology can become an aid to, or even an exercise in, contemplation. Fourth, and finally, a greater appreciation for the beauty of this truth will deepen our love for God.

What Is the Doctrine of the Trinity?

What we are seeking to understand, quite simply is

this doctrine: God is three persons, one in being.

As the Nicene Creed states, “We believe in one God” Beneath that affirmation we state our belief in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This is fully backed up by Scripture. For example:

I and the Father are one. – John 10:30

In Christ all the fullness of the Deity dwells in bodily form. – Colossians 2:9

Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. – Matthew 28:19

Let’s unpack this a bit. We proclaim there is one God, not three Gods. What is ‘three’

about God is not His being but the persons. Since there is one being, each

person is fully God. The Father is fully God, as is the Son, as is the Holy

Spirit.

This might sound like a riddle or paradox to some.

How can this be?

Explanations That Don’t Work

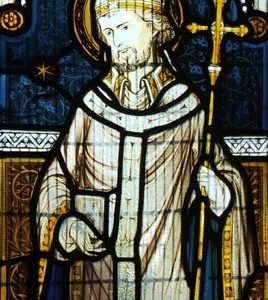

Before turning to one of the best explanations ever

offered in the history of the Church, it might help to point out what does not

work. St. Patrick’s famous metaphor of the three-leaved shamrock falls short

because each of the leaves is separate from the other. The Father does not

exist apart from the Son or the Holy Spirit.

Another common metaphor is that of water. We can talk about there being one substance of water that exists in three states — ice, liquid, and gas. Yet this metaphor fails because water is never fully ice, liquid, and gas at the same time. Yet God is always the Father Son and Holy Spirit. He is not the Father at one time, the Son at another, and the Holy Spirit at another. As this site points out, this is the heresy of modalism, that the persons are not real, but merely ‘modes’ through which God appears to us.

One metaphor I life is that of a nice shiny metal sphere. It has one substance — the metal itself. But there are three things about it that fully share in this substance. First, there is its roundness. The roundness is something that encompasses the whole sphere. Second, there is its color. Let’s imagine that it’s that dark muddy bronze color you get when you rub oil on your fingers. The whole sphere is this color. Third, the sphere is very smooth. Like the shape and the color, the smoothness is something that applies to the whole substance of the sphere. We could say there is one metallic sphere, round, muddy bronze, and smooth.

But this metaphor readily breaks down. What we are

talking about are characteristics of the sphere, not things intrinsic to it. We

could paint it another color. We could hammer in one side so it is less smooth.

We could take a sledgehammer to it so it is no longer perfectly round. It is

material, changeable, and divisible—quite unlike God.

Explaining How God Can Be One and Three

The Church Father St. Augustine found a solution to

the problem of metaphors for the Trinity. Rather than looking outward to the

material world, he looking inward at the immaterial mind. Within ourselves, he

asked, do we find something that is one and three at the same time?

Augustine found an answer in the mind and its

memory, knowledge, and love of itself.

The mind’s memory is the source of its knowledge. In

remembering itself, the mind brings forth knowledge of itself. And when it sees

what it is, the mind should, at least in a healthy person, love itself.

The whole of the mind is in each of these three. Everything that it is, thinks, and has done is contained in its memory. Likewise, in knowing itself, it knows its whole self. In a sense we could say the whole of the mind is contained in its knowledge of itself. And again, it is its whole self that it loves and contained in that love.

To paraphrase Augustine, then, there are these three—memory, knowledge, and love. But there are not three minds, just one. So there is a sense in which the mind is both one and three. It is both one thing—mind—but also three—memory, knowledge, and love.

(A note to readers: I am simplifying and combining what are actually two analogies Augustine draws from the mind. This simplified version is also the one employed by St. Thomas Aquinas. For more, read Augustine’s On the Trinity, available here and here, and Aquinas’ Summa Contra Gentiles here.)

We can see a clear parallel between the mind and the

Trinity. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are analogous to the mind’s

memory, knowledge, and love of itself.

The Catholic Catechism calls the Father “the source and origin of the whole divinity”—analogous to the way our memories are the source of the mind’s knowledge and love of itself. The Son is associated in our faith with God’s self-knowledge, which is why He is also called the Word and Wisdom of God (see John 1:1 and 1 Corinthians 1:24). And, finally, the Holy Spirit is associated with the love of God (see Romans 5:5).

So, the analogy of the mind not only explains the

seeming paradox of how something (or someone) can be one and three, it also

explains the particular three that we see—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Explaining Why The Three Are Persons

There are two questions that have yet to be

answered. Because we are out of space, short answers will have to suffice.

First, why is what is three in God called persons?

Remember, Aquinas says, that a person is “an individual substance of a

rational nature.” On first blush that seems to work quite well. But hold on.

Something shouldn’t sit well with us in thinking about individuals within God.

Surely Father Son and Holy Spirit are not three individual persons having the

divine nature in the same way that John, Joe, and James are three persons

having a human nature.

Aquinas readily recognizes this objection. He notes

that ‘individuation’ only happens when we’re talking about matter—which we

have, but God doesn’t. So when it comes to God, we have to recognize that we

use the word ‘person’ with a meaning somewhat different than when we talk about

man. In the case of God, Aquinas says we have to use Richard of St. Victor’s definition

of a divine person as “the incommunicable existence of the divine nature.”

In other words, the Father Son and Holy Spirit

really exist and they are distinguishable from each other. The Father is God.

The Son is God. The Holy Spirit is God. The Father is not the Son. And the Son

is not the Holy Spirit.

In a way, the above example of John, Joe, and James

can help us understand this. If a skeptic ever asks how there can be three

persons of a rational nature just point out that you and your friend, and third

person are living proof that it is possible. The giant difference that vastly

separates God from mankind is that there are ‘no individuals.’ The more you can

understand that truth the more you can begin to understand the statement that

God is one in being and three persons.

But perhaps there was some wisdom in Augustine’s

concession that we can’t really know what a person means when applied to God: “Yet

when you ask ‘Three what?’ human speech labors under a great dearth of words.

So we say three persons, not in order to say that precisely, but in order not

to be reduced to silence.”

Why There Are Three Persons

The second question is why there are three persons. Why not four? Or five? In

his work the Summa Contra Gentiles,

Aquinas points to Augustine’s analogy of the mind for the answer. And here it

is quite simple. The reason there are not more than three is that God perfectly

remembers, knows, and loves Himself. There is no need for anyone else.

So the doctrine of the Trinity is something we can understand. But ultimately our understanding is quite limited and we cannot avoid finding ourselves eventually reduced to silence in wonder before the mystery.

✠