This Present Paradise: A Series of Reflections on St. Elizabeth of the Trinity (Read part 3 here)

(Read part 3 here)

When you created these poor eyes of mine,

drawing them from the deep into your open hand,

You were thinking of that eternal gaze

enraptured by the endless deep,

and You said:

I will lower myself, brother, and never

leave your eyes in solitude.

-Pope St. John Paul II, Song of the Inexhaustible Sun

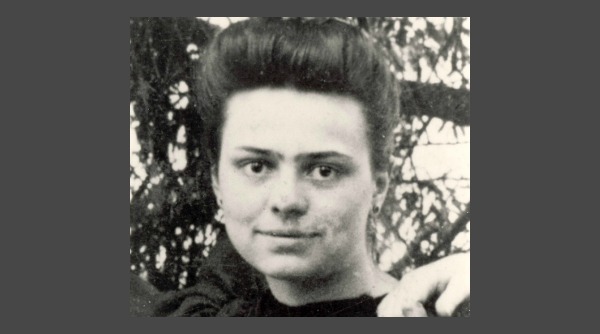

No one could ever, I think, see a photograph of our saint and not be struck immediately by the depth behind her large, dark eyes. She always loved the idea of an “abyss”—an immense depth, whether it be the chasm of her own nothingness or the profundity of God’s love. And somehow, that endlessness seemed to reach from far behind her gaze. Maybe it was because interiorly, she was constantly gazing at something—Someone—only she could see, who never left her “eyes in solitude.”

Elizabeth Catez had always had striking eyes. Flashing and fiery, from the first they revealed a strong will and an unchecked temper. “A real devil,” her own mother called her, prone to frequent tantrums and stubborn outbursts. Her parish priest observed that she would become “either a saint or a demon.” Perhaps we can relate to her and struggle with this unyielding intensity in ourselves. Maybe we have someone in our lives whose assertiveness can be both a blessing and a curse, and understand better her mother, who was reduced to packing a bag with Elizabeth’s things and threatening to send her to the house of corrections down the street!

For someone with a choleric temperament (which she must have had), it is absolutely true that their best assets are their iron will, determination, decisiveness, and confidence, all of which make the greatest of reformers, founders of orders, leaders, and—saints. Think St. Paul or St. Ignatius of Loyola. But without conversion of heart and conformity to Christ, a choleric can be angry and domineering. Luckily, little Elizabeth would begin to surrender herself to grace before the negative traits took hold in her soul. Her ‘conversion’, she said herself, began with her first confession.

That encounter with Christ in the sacrament of His Mercy began to open her conscience, and, no longer closed in by her own selfishness, she began to realize what her fierce and unrelenting temper was doing to those closest to her—and to her own soul. She began to cooperate with grace, giving it greater space within. The interior abyss was beginning to grow. Maybe it was then her eyes began to soften, a little. It was a long road to sanctity, still—her mother had to threaten that she might not receive her First Holy Communion if she didn’t improve, but it was a start.

She wrote a letter to her mother on the occasion of the New Year in 1889, when she was nine years old. “I’m going to be a very gentle little girl,” she wrote, “patient, obedient, conscientious, and not falling into tempers. And since I’m the elder I must set my sister a good example; I won’t quarrel with her anymore, but I’ll be such a little model that you’ll be able to say you are the happiest of mothers, and since I hope to have the happiness of making my First Communion soon, I will be even more well-behaved, and I’ll pray to God to make me even better.”

She would remain the same girl, with the same strong temperament, but she began to work so hard to control her anger that she would sometimes cry silently from the effort. Surrender is so painful. But she already loved the One to whom she was surrendering herself and her faults, and He was preparing her for Himself.

Then a miracle will be,

a transformation:

You will become me,

and I—eucharistic—You.

– Song of the Inexhaustible Sun

Image credit: Willuconquer [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

This article originally appeared on SpiritualDirection.com and appears here with kind permission.