On a regular basis we hear in the news that certain priests and prelates are involved in mortal sins that bring opprobrium to the Catholic Church. We cannot read the minds and hearts of such men but their behavior makes many thoughtful Catholics ask whether they even believe the teachings they have been charged to promulgate.

Do such men even believe that they will be held accountable

at the Particular and General Judgments and that the road to perdition is paved

with such things as homosexual predation, cover-ups, embezzlement, and other

kinds of ecclesial malfeasance? Perhaps they’re so convinced that hell will be

empty that they’re not worried about receiving everlasting punishment for their

deeds (Mt. 25:46) or, in only looking at the present moment, they’re simply

sacrificing their integrity on the altar of ecclesial survival.

On the other end of the spectrum are Catholics who are so

convinced of the truth of the faith once delivered (Jude 3) that they are

willing to risk imprisonment and even martyrdom in practicing such a faith.

Such was the family that Athanasius Schneider, the auxiliary bishop of Astana,

Kazakhstan, was born into.

Schneider’s parents were Black Sea Germans from the Ukraine

whom Stalin sent to the gulag in Krasnokamsk in the Ural Mountains after the

Second World War. They were active in the underground church, and Schneider’s

mother, Maria, was one of many people who helped shelter Blessed Oleska

Zarycki, a Ukrainian priest, who was later martyred in 1963.

“Faith is a gift of God, a supernatural virtue infused by

him” (CCC 153; emphasis theirs). This family had supernatural faith and it

was reflected in their holy reverence and adoration in the celebration of the

Eucharist, that, because of Soviet persecution, was prohibited and rarely

available to them in their clandestine meetings.

In one such meeting, when a Father Alexij Saritski was

beginning to celebrate Holy Mass, a voice was suddenly heard: “The police are

coming!” Later that evening, Maria Schneider left her two small children with

her mother, and with the help of another woman (the aunt of her husband), took

Father Saritski to safety, after trekking 12 kilometers through the forest with

temperatures reaching 22 degrees below zero.

In recent years, whether Schneider is weighing in on clergy sex abuse, interreligious relations, or immigration, his holy pedigree and orthodox sensibility come through in his statements. Thus, it was with great interest that I recently read his 2008 book on Holy Communion, Dominus Est-It is the Lord!

If you subtract the Publisher’s Foreword, Preface, and

Glossary of Names, which were not written by the bishop, his work actually only

amounts to about 39 pages and serves more as an extended essay than an

exhaustive book. Whether you agree with his convictions or not, you have to

respect his deep reverence and adoration of the Eucharist.

This sense of the sacred has been lost by many parishioners in the Catholic Church in America and is reflected in how we behave and dress. Chewing gum is more common; people wear sweat pants, tank tops, tube tops, spaghetti straps, flip flops, beach sandals, and sometimes dress immodestly.

The Eucharist is sometimes received like a guy grabbing a

beer from a vendor at a minor league baseball game. No wonder many earnest,

young Catholics are running like frightened antelope to the Latin Mass.

In 1997 Schneider received his doctorate in patrology from

the Augustinianum in Rome, and in 1999, he was appointed professor in the Major

Seminary of Karaganda in Kasakhstan, Central Asia. From his immersion in patristics,

he has concluded that:

“The organic development of Eucharistic piety as a fruit of the piety of the Fathers of the Church led all the Churches, both in the East and the West, already in the first millennium, to administer Holy Communion directly into the mouths of the faithful. In the West, at the beginning of the second millennium, there was added the profoundly biblical gesture of kneeling. In the various liturgical traditions of the East, the moment of receiving the Body of the Lord was surrounded by various awe-inspiring ceremonies, often involving a prior prostration of the faithful to the ground.”

Schneider doesn’t deny that communion-on-the-hand took place

in some communities in the Early Church, but buttresses his case for an

“organic development” with two citations from Pope Gregory the Great. Those who

continued the practice of distributing Communion in the hand received the

Church’s censure.

Sacred ministers were threatened with suspension at the

Synod of Rouen in 650 if they distributed Communion in the hand A schismatic

sect known as the Casiani was condemned at the Synod of Cordoba in 839 for

refusing to receive Communion on the tongue.

Since it is not an exhaustive treatment of the subject,

other important citations were not mentioned such as the Sixth Ecumenical

Council of Constantinople in 680/681 which forbade believers from taking

Communion in the hand and threatened those who did with excommunication. One

could also reference Thomas Aquinas and the Council of Trent.

Schneider quotes the noted liturgist, Joseph Jungmann, who explains that with the Eucharist being administered directly into the mouth, many problems were solved: “…the need for the faithful to have clean hands; the even graver concern that no fragment of the consecrated Bread be lost; the necessity of purifying the palm of the hand after reception of the Sacrament.”

The good bishop is definitely his mother’s son in

prescribing an attitude of deep reverence and adoration in receiving Holy

Communion. He quotes an ancient Coptic liturgical tradition, the Ordo

Communionis (Order of Communion): “Let all prostrate on the ground, small

and great, and then they will begin to distribute Communion.”

Such sentiments, Schneider avers, were also echoed in St.

Augustine and St. John Chrysostum. Before he was the pontiff, Cardinal

Ratzinger said, “kneeling is the right, indeed the intrinsically necessary

gesture” before the living God. In the Publisher’s

Foreword to the book, Reverend Peter M. J. Stravinskas wonders aloud “if Bishop

Schneider’s …book did not play a part in the decision of Pope Benedict XVI to

return to the traditional mode of Communion, namely, on the tongue to kneeling

communicants.”

Our Mass here below participates with the Divine Liturgy

that is now going on in heaven. In that sacred realm the twenty-four elders are

bowing down to the Lamb day and night.

Schneider also asserts that receiving the Body on the tongue

while kneeling is consonant with an attitude of reverent humility that children

have in receiving the kingdom of God (Lk. 18:17). He quotes St. John

Chrysostom: “…see with what food he satisfies us. He himself is our food and

nourishment; and just as a woman nourishes her child with her own blood and

milk, Christ also constantly nourishes with His own Blood to those whom he has

given birth [by Baptism].”

The good bishop concludes his extended essay by saying that

such child-like humility and adoration could be a powerful witness to (post)

modern man and the non-Catholic. He could have an encounter with the Wholly

Other God and “falling on his face, will worship God and declare

that God is really among you” (I Cor. 14:25).

This encounter with Transcendence highlights the infinite qualitative difference between creature and Creator, a distance that is traversed by the Mercy of God incarnate in the Eucharist. This will cause them to bow in his Presence with thanksgiving because the chasm has been bridged, and, like Jacob, come away declaring, “Surely God is in this place!” (Gen. 28:16).

✠

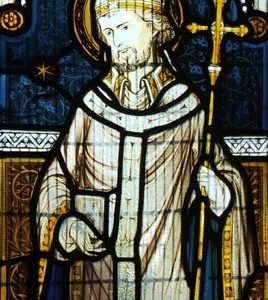

image: Bishop Athanasius Schneider O.R.C. celebrating Traditional Latin Mass in Tallinn, Estonia / Marko Tervaportti [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons