Has none but this foreigner returned to give thanks to God? (Lk 17:18)

Around the world, St. Frances Xavier Cabrini is fondly remembered as a devoted servant to her countrymen. She founded her congregation to serve Italian immigrants seeking a better life for themselves and their families. This was not simply window dressing: around the turn of the previous century, the challenges faced by Italian Americans (and other immigrant groups) were immense. While work was plentiful, it was often grueling and hazardous. Immigrants were despised by many for their ignorance of English and of American customs in general. Their neighborhoods lacked proper sanitation and health services, the cause of much suffering for the unfortunate residents. Tenement buildings, while a vast improvement on earlier urban housing, were often poorly maintained.

Even as they adapted to their new homeland, they were still viewed as less than fully American. Whenever they were deprived of their wages, or suffered from other wrongs, the local police did not always feel compelled to enforce justice—as several accounts of my own family’s history can attest.

St. Frances did not see herself as an apostle to her own people, but she was well prepared by her own sufferings to bear the sorrows of those in need. Weak as a child, and prone to illness, the congregation she sought to join thought her physically incapable of living the vocation. Undaunted, she became a public school teacher, eventually being called upon to head the reform of a lapsed religious community in her native Italy. While she thrived in this role, she had a wider purpose: like St. Dominic, who wished to evangelize the Cumins and the Tartars, she too hoped to work in the East, amongst the Chinese. And, like St. Dominic, she felt a strong desire to submit her designs to the Holy Father and to receive his decision. Pope Leo XIII knew much of the suffering that Italian immigrants faced throughout the world, and prevailed upon Mother Cabrini to serve those closer to home with the same reasoning that compelled Holy Father Dominic to seek out the lost in southern France.

And so, well prepared by her own sufferings, she accepted the Pope’s charge, and accepted still more sufferings for the sake of the mission. Deathly afraid of sea travel, she nevertheless crossed the Atlantic—over the course of her life, she managed over thirty transatlantic voyages. When she first arrived in New York, Archbishop Corrigan advised her that the school she had been sent to manage in the United States had been dissolved—the pressing work that Leo XIII had entrusted to her was no longer necessary. Instead, he recommended that she should just head back to Italy, as there was no need for her anymore in America. Mother Cabrini knew better than to settle for this: the Holy Father had sent her to this country, and so she would stay. Perhaps unsurprisingly in retrospect, her ministry quickly began to flourish.

For all the challenges she faced in serving immigrants, she did not have to confront one difficulty that we associate with assisting migrants today: bureaucratic and legal obstacles to entering the country. While Ellis Island is famous for screening all seeking admission into the United States, its sole purpose was to prevent the admission of communicable diseases from immigrants. Beyond this, families and individuals were free to come and go as they pleased with no injury to their “immigration status.” Families (including my own) thought nothing of moving to America, returning home, then moving back to America again a few years later. The modern immigration system as we have it today—with quotas, waiting periods, and countless other restrictions—only dates from the mid-1920s. St. Frances Xavier Cabrini was taxed with many burdens for her ministry to immigrants, but an onerous amount of paperwork was not one of them.

This fact struck me with particular force this past summer, as I was assigned to work in the immigration office of the Diocese of Providence. Having witnessed what it takes to become an American citizen, it seems fair to say that much of the process, with all its paperwork, stems from the prudent determination to preserve the quality of life for Americans. However, it must also be said that the documentation is often processed in an arbitrary manner. The government proposes to treat all those applying for citizenship fairly, but often treats would-be citizens with a presumption of guilt over any problem that appears in their documentation, or that arises in the interview process.

Catholic social teaching certainly emphasizes the right and duty for nations to safeguard their citizens and their borders. The Church is just as insistent, however, that immigrants be welcomed and treated fairly, and without unnecessarily onerous requirements—in recognition of the fact that we all have been intended to share a common citizenship.

St. Frances Xavier Cabrini is justly remembered as the first citizen of the United States to be canonized a saint. However, both sanctity and citizenship came to Mother Cabrini not by blood, nor through force of will, nor a single gesture on her part, but through her submission to ongoing change. Naturalized by passing a written exam, she became a citizen of heaven through a starker test: whether the spark of Divine grace she received in her heart could be fanned into transforming flame. Some can claim to be native-born citizens of an earthly city, but given this test no one on earth can claim to be a “native-born” saint. Rather, only this spark, won by Christ’s victory, can lead us to glory in the Eternal Jerusalem.

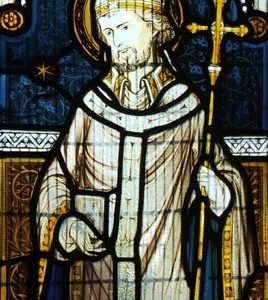

image: St. Frances Cabrini by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. / Flickr

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on Dominicana and is reprinted here with kind permission.