The following is an excerpt from The Quran with Christian Commentary: A Guide to to Understanding the Scripture of Islam. Copyright © 2020 by Gordon Nickel. Published by Zondervan. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

The following is an excerpt from The Quran with Christian Commentary: A Guide to to Understanding the Scripture of Islam. Copyright © 2020 by Gordon Nickel. Published by Zondervan. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

[Browse the Understanding Islam section in the Bible Gateway Store]

[Read the Bible Gateway Blog post, Loving Our Muslim Neighbors During Ramadan]

From the Introduction

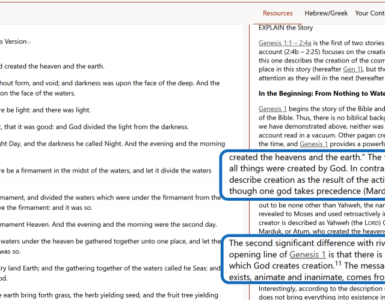

The Quran is the scripture of the Muslim community, revered by Muslims around the world and given authority by them to instruct both faith and life. Its 114 chapters, called sūras, are arranged approximately in order of length from longest to shortest. The entire collection is introduced by a short prayer known as al-Fātiḥa, or “the Opening.”

The contents of the Quran come from the Middle East in the seventh century AD, though scholars do not agree on precisely how or where it came together. The Quran that most Muslims use today reflects a decision of Muslim leaders in Egypt in 1924 to adopt one particular “reading” of the text from among many possible and officially accepted readings.

This commentary is an attempt to explain the contents of the Quran to non-Muslim readers alongside the full translated text of the Quran. The Muslim community believes the Quran to be the word of Allah. The Quran addresses the Muslim community as “you who believe” (e.g., 2.104) and assumes that its assertions and commands will be accepted by them….

It conceives its contents to be not only for those who accept its claims but also for those who reject them. In this sense the Quran makes an open appeal to all of humankind. Since the Quran addresses itself to non-Muslims, a careful study of its contents and a response to its claims from non-Muslims is clearly appropriate.

[Read the Bible Gateway Blog post, No God but One: Allah or Jesus?—An Interview with Nabeel Qureshi]

Salvation in the Quran

by Peter Riddell

Salvation is far less clearly defined as a doctrine in the Quran than in the Bible. Nevertheless, the Quran contains elements that help Muslims prepare for a positive outcome on the Day of Judgment.

Quranic Arabic makes use of the verb najā to express the notion of “deliver” or “save.” The use of this verb is less associated with an expression of hope and more commonly coupled with delivery from punishment for those who follow the divine commands, as well as delivery denied to those who disbelieve.

[Read the Bible Gateway Blog post, Interview: Nabeel Qureshi, author of Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus]

The verb rarely appears in sūras usually associated with the earliest part of Muhammad’s ministry in Mecca. At this early stage the architecture of quranic doctrine was somewhat in flux; the messenger is believed to have been engaging with and responding to challenges in the marketplace as he preached. The single reference from this period at 70.14 is concerned with a divine rebuke to disbelievers who will be ready to “ransom” (v. 11) family members on the Day of Judgment in order to save themselves, but to no avail. The medieval commentator Ibn Kathīr expands on the quranic idea of salvation in this verse in the following terms: “Even the child that he had who was dearer to him than the last beat of his heart in the life of this world, he would wish to use the child as a ransom for himself against the torment of Allah on the Day of Judgment when he sees the horrors. However, even this child would not be accepted from him as a ransom.”

In chapters seen by Muslims as reflecting the messenger in a later period in Mecca, the Arabic form anjā occurs with increasing frequency. The dichotomy between believers and unbelievers takes shape more clearly in these chapters. At this stage the Quran was issuing both promises of reward and increasingly stern warnings of divine punishment. The concept of deliverance or salvation hinges on several key elements. First, God remains in control of the distribution or denial of salvation. He saves the obedient and leaves others to stray (19.72) or destroys them (21.9). In some cases God predestines some to miss out on salvation (27.57). God’s sovereignty is spelled out clearly, rewarding the obedient and punishing the sinners (7.72, 165; cf. 12.110: “Those whom We pleased were rescued. But Our violence was not turned back from the people who were sinners”).

A second key element is the method of God’s identification of who is to be delivered or saved. At 27.53 we encounter a clear statement that God saves “those who believed and guarded (themselves)” (cf. 21.88). Elsewhere the Quran makes it clear that God delivers certain people or groups as “a blessing” or a reward to “the one who is thankful” (54.34–35; cf. 39.61; 41.18). The prophets are often identified in the Quran as the beneficiaries of God’s salvation, because they have believed and provided a righteous model for others (10.103). For example, Abraham was saved from the fire (29.24), while Moses was saved from being apprehended after he slew the Egyptian slave master (20.40; 26.66). Lot was saved “from the town which was doing bad things” (21.71, 74; 29.32), Noah was delivered when he cried out and was heard by God (21.76; 10.73; 29.15), and Hud was saved, along with his fellow believers (11.58), as were Salih (11.66) and Shu‘ayb (11.94).

The deliverance or salvation represented by the verb anjā not only relates to end-time salvation. Indeed, the Quran uses the verb on occasion to refer to saving a physical person who then turns away through ingratitude (6.64; 10.23; 17.67). The famous Jalalayn commentary is specific on identifying the sin after salvation in 6.64: “Say, to them: ‘God delivers you from that and from every distress, [from every] other anxiety. Yet you associate others with Him.’”

In the sūras attributed by Muslims to Muhammad’s Medinan period, the verb anjā occurs infrequently. By this stage, in terms of Muslim understanding, Muhammad’s authority as the messenger of God has been firmly established, and the message of deliverance/salvation and reward has been clearly articulated. What predominates in these chapters is a resounding warning of the dire punishments awaiting disbelievers and the disobedient. Even when the verb anjā does occur, it is collocated with references to punishment: “You who believe! Shall I direct you to a transaction that will rescue you from a painful punishment?” (61.10).

Apart from the specific use of the verb anjā, how does the Quran advise Muslims to avoid eternal punishment in the hereafter? The core notion is through obedience to God’s commands by following the guidance of the prophets and the divine Law. This is well summarized in 103.2–3, which Muslims consider to originate from the early part of Muhammad’s ministry, where the message of following the Law and the Prophets is clearly articulated: “Surely the human is indeed in (a state of) loss –except

for those who believe and do righteous deeds, and exhort (each other) in truth, and exhort (each other) in patience.”

[Read the Bible Gateway Blog post, Evangelism: The Romans Road to Salvation]

The Quran with Christian Commentary is published by HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc., the parent company of Bible Gateway.

See what you’re missing by not being a member of Bible Gateway Plus. Try it right now!

The post The Quran with Christian Commentary appeared first on Bible Gateway Blog.