Well, this Religion News Service piece sure has an interesting premise. I am talking about a lengthy feature — seen here in the Washington Post — that implies American Christianity is racist because of one popular painting of Jesus Christ.

Never mind that many of us have grown up disliking the painting for its sickly sweet religiosity. Never mind that this is not the iconic image seen in Christian traditions with ancient roots and liturgical art that reveals those roots in the Middle East. There’s a crucial word missing in this piece — “Jewish.”

Even as a child, this particular image repelled me, as it didn’t reflect the lively, infuriating and suffering Jesus I saw in the Bible. There’s an assumption that Americans adore this image.

Now, our modern-day iconoclasts want to get rid of it.

CHICAGO — The first time the Rev. Lettie Moses Carr saw Jesus depicted as black, she was in her 20s.

It felt “weird,” Carr said.

Until that moment, she had always thought Jesus was white.

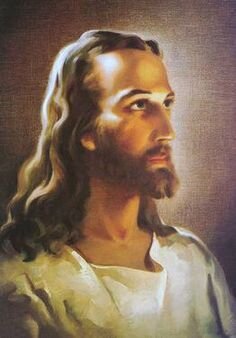

At least that’s how he appeared when she was growing up. A copy of Warner E. Sallman’s “Head of Christ” painting hung in her home, depicting a gentle Jesus with blue eyes turned heavenward and dark blond hair cascading over his shoulders in waves.

The painting, which has been reproduced a billion times, came to define what the central figure of Christianity looked like for generations of Christians in the United States — and beyond.

“Some in the church,” the reporter says, are calling for the eradication of that painting because it makes Jesus look white with blue eyes.

Folks, haven’t we been here before?

Remember the dust-up in 2013 when Megyn Kelly told us all that Jesus was white?

Here is a lengthy passage from the RNS piece, containing lots of history of this particular image:

The “Head of Christ” has been called the “best-known American artwork of the 20th century.” The New York Times once labeled Sallman the “best-known artist” of the 20th century, although that few recognized his name.

“Sallman, who died in 1968, was a religious painter and illustrator whose most popular picture, ‘Head of Christ,’ achieved a mass popularity that makes Warhol’s soup can seem positively obscure,” William Grimes of the Times wrote in 1994.

The famed image began as a charcoal sketch for the first issue of the Covenant Companion, a youth magazine for a denomination known as the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant.

Sallman, who grew up in the denomination, which is now known as the Evangelical Covenant Church, was a Chicago-based commercial artist. Wanting to appeal to young adults, he gave his Jesus a “very similar feeling to an image of a school or professional photo of the time making it more accessible and familiar to the audience,” said Tai Lipan, gallery director at Indiana’s Anderson University, which has housed the Warner Sallman Collection since the 1980s.

His approach worked.

The image was so popular that the 1940 graduating class of North Park Theological Seminary in Chicago commissioned Sallman to create a painting based on his drawing as their class gift to the school, according to the Evangelical Covenant Church’s official magazine.

OK, so this painting was done 80 years ago in an era when a lot of American Protestant religious art was quite sentimental.

The article explains that the painting became wildly popular, accompanying soldiers into battle during World War II and ending up on prayer cards and was seen in a wide range of churches — Catholic and Protestant, evangelical and mainline, white and black.

Sallman wasn’t the first to depict Jesus as white, Morgan said. The Chicagoan had been inspired by a long tradition of European artists, most notable among them the Frenchman Leon-Augustin Lhermitte.

But against the backdrop of U.S. history, of European Christians colonizing indigenous lands with the blessing of the Doctrine of Discovery and enslaving African people, Morgan said, a universal image of a white Jesus became problematic.

“You simply can’t ignore very Nordic Jesus,” he said.

Jesus was a first-century Jewish man and probably looked like the 21st-century denizens of the Middle East; namely, olive-skinned, dark-haired and with black or brown eyes.

Back in the 1940s, not a whole lot of folks were traveling to Palestine, as the British had been running the place since 1917 and the country was a mix of Jews, Arab Muslims and Armenian Christians. People didn’t travel widely overseas like they do today and certainly not to a backwater like Jerusalem and its environs.

So I think that it’s understandable why Sallman wouldn’t have had a clue as to what the area’s inhabitants looked like. So he drew what he knew, for an American audience.

Eighty years later the result is being seen as a form of white supremacy, as the article goes on to explain.

This week, the activist Shaun King called for statues depicting Jesus as European to come down alongside Confederate monuments, calling the depiction a “form of white supremacy.”

The science fiction author Nnedi Okorafor echoed that sentiment on Twitter.

“Yes, ‘blond blue-eyed jesus’ IS a form of white supremacy,” she tweeted.

Anthea Butler, an associate professor of religious studies and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania, has also warned of the damaging impact of depictions of white Jesus.

“Every time you see white Jesus, you see white supremacy,” she said recently on the Religion News Service video series “Becoming Less Racist: Lighting the Path to Anti-Racism.”

Sallman’s Jesus was “the Jesus you saw in all the black Baptist churches,” Butler told RNS in a follow-up interview.

I am glad one academic was quoted. Still, are we are hanging the rest of this story on the whim of a Twitter activist who wants to basically tear down every statue on U.S. soil that he doesn’t like and a science fiction author? Like, why do we care what those two people think?

Fortunately the article does cite artists who have portrayed Jesus as Korean or Maōri or black or any number of other races and ethnicities because of the universality of his message and claim to be God in human flesh.

But nowhere does it say what he really was: a Jewish man from the Middle East. A simple Google search took me to this 2018 piece in TheConversation.com about the brownness of Jesus’ skin.

In a piece earlier this year on the iconography of Jesus through the ages in The Dartmouth, a publication of Dartmouth University, the author notes that not all European artists portrayed Jesus as a white guy. Rembrandt used a Jewish model in Amsterdam for his 1648 “Head of Christ” painting, and French artist Marc Chagall emphasized Jesus’ Jewish appearance during the 1930s in his personal battle against rising anti-Semitism.

The article refers to the “earliest images of Jesus,” but never follows through with any content about centuries of Eastern Orthodox iconography and other older traditions concerning the appearance of Jesus.

The realization that Jesus wasn’t white hasn’t been news for awhile. Check out these essays about what Jesus clearly looked like in Baptist News and in BBC, which explains that Jesus probably had short hair (unlike most film depictions of him) and wore ordinary-colored clothing, not the white robes that filmmakers like to put him in.

Speaking of which, why aren’t these Twitter critics going after our movie industry? Remember Jeffrey Hunter, the American actor who played Jesus in the 1961 film “King of Kings?” (OK, he had brown hair but he also had blue eyes).

This is a complex topic to write about. If you do, ask the right questions, like why black churches posted this painting of Jesus. No one was forcing them too. There’s been other representations of Jesus out there since at least the 6th century. And point out what Jesus really looked like: A Jewish man who was so poor, he only had one robe to his name.

MAIN IMAGE: This painting is from “The birth of Jesus with shepherds,” drawn from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, Tenn.