Woman, what have I to do with thee?

This question—posed by Jesus to Mary after she asks for His intervention at the wedding at Cana in John 2:4—is often cited by Protestants attempted to refute Catholic devotion to Mary. The translation above—which dates back at least to the King James Bible—has even seeped into some Catholic translations.

Of course, as Catholics we know that in addressing her as ‘woman’ Jesus was universalizing Mary’s role in salvation history, identifying her both as the New Eve and looking forward to her role at the crucifixion and later in the Book of Revelation. We know that, even though He hesitates, Jesus relents and performs the desired miracle, thereby marking the start of His ministry and confirming His mother’s intercessory role.

But there’s an even simpler reason why the Protestant interpretation is so wrong: Jesus did not actually say that to His mother.

The original Greek yields a different reading. The most literal translation goes like what the Douay-Rheims Bible has: ‘Woman, what is that to me and to thee?’ This reflects the Greek where the pronouns for ‘me’ and ‘you’ are used with an ‘and’ connecting them.

This seemingly minor error in translations has immense ramifications. Suddenly, rather than seeming like a rift between Jesus and Mary, Jesus’ words make it seem like they are in this together. A fair paraphrase of their words might go something like: How should we intervene? What should we do about this?

His response thus intensifies Mary’s intercessory role. Rather than balking at it and only later giving in to her request, Jesus affirms Mary’s participation in His redemptive mission.

This dynamic recasts our interpretation of His address to her as ‘woman.’ Not only is He affirming the universality of Mary as the New Eve, He is also using a form of royal address. As one commentator notes, the Greek tragic writers employed ‘woman’ in “addressing queens and persons of distinction” and the Roman historian Cassius Dio quotes Augustus as doing the same with Cleopatra.

The reality of Mary’s queenship is relevant because in the Old Testament one of the functions of the queen mother was to intercede on behalf of others for her son. This is illustrated in 1 Kings 2:

Adonijah, son of Haggith, came to Bathsheba, the mother of Solomon. “Do you come in peace?” she asked. “In peace,” he answered, and he added, “I have something to say to you.” She replied, “Speak” (verses 13-14).

Adonijah proceeds to ask her to pass on a request to Solomon that he be allowed to marry Abishag the Shunamite. She then refers to the matter to Solomon. Notice how he responds to her:

Then Bathsheba went to King Solomon to speak to him for Adonijah, and the king stood up to meet her and paid her homage. Then he sat down upon his throne, and a throne was provided for the king’s mother, who sat at his right. She said, “There is one small favor I would ask of you. Do not refuse me.” The king said to her, “Ask it, my mother, for I will not refuse you.” So she said, “Let Abishag the Shunamite be given to your brother Adonijah to be his wife” (verses 19-21).

Intriguingly, this Old Testament precedent is also wedding-related. It also occurs at the very beginning of the reign. In fact, it is the first story of Solomon’s reign recorded in 1 Kings. The verse immediately preceding this one reports that Solomon had just been seated and that his thrown had been ‘established.’

In John 2, then, we can see Mary’s intercession as also contributing to the establishment of Christ’s kingdom, which was to be a quite different one than visible, material kingdoms. In fact, in some ways it would become the complete opposite of any human standard of what it means to establish a kingdom—ending in the scattering of His already-small band of followers, His condemnation as a criminal, and, finally, the crucifixion of the king.

This event is foreshadowed at Cana where, as many Catholics well know, the changing of the water into wine anticipates the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. Moreover, Jesus declaration that His ‘hour’ had not come also points to the cross: in John ‘hour’ typically refers to Jesus suffering and death.

What doesn’t get sufficient emphasis is the significance of Mary’s role in all this. In his book, Life of Christ, Bishop Fulton Sheen suggests that Mary’s order to the servants to do whatever Christ tells them came after she grasped the full implications of what she was asking Jesus to do. We could probably be more pointed than this: there really is a direct line we can draw from her intercession here and what happens on Golgotha. In other words, it would not be an exaggeration to say that her intercession helps to bring about the crucifixion.

Much as her consent was essential to the Incarnation—her ‘Yes’ and fiat to God—so also was her active participation critical to the redemption.

Her queenship intensifies this sense of sorrow. For this involves much more than a mother giving up her son. Just as Jesus contradicts worldly standards of what a king should be and do, so also does Mary depart from the mold of queen mothers in the ancient world. She helps her son establish His kingdom, but she does so in the most strange way—by asking Him to offer Himself up in self-sacrifice.

John reports that in response to Jesus’ message Mary—already anticipating His action—issues this order to the servants at the wedding: “Do whatever he tells you.” Those are her last recorded words in the gospels. Having set in motion the events leading to the Passion of the Son, Mary has no need to say anything else. At that point, her intercession had already achieved more than that of any other mere human being in history, past and future.

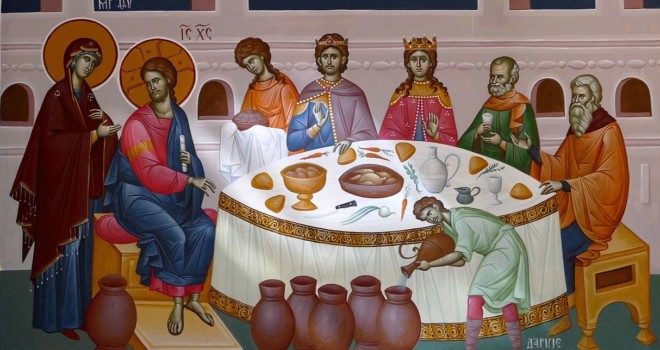

image: By © Ralph Hammann – Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0 ], from Wikimedia Commons