In times of insanity, only the relatively insane have the courage to be sane. In this paradox lies the paradox of salvation itself: that the seemingly mad are the ones to save the world from madness. St. Ignatius of Loyola was a knight errant for Our Lady who charged the giant windmills of his lifetime with the unconquerable valor of Don Quixote, proving himself, though often battered and bruised, a mighty champion who led an army on for the greater glory of God.

In a tumultuous century for the Catholic Church, where Pope Leo X fussed as Luther became popular, and Hadrian VI fussed against the Turks, and Clement VII fussed with the Habsburgs, and Paul III fussed over commissions from Michelangelo, a knight was born to the Church in the Castle of Loyola in Guipuscoa, Spain, 1491. Ignatius was reared from his boyhood in the arts of chivalry in the court of Ferdinand V of Aragon.

Known for his eyes that pierced like swords, Ignatius was driven by youthful daydreams of military prowess. After his riotous and amorous service at court, he was stationed at the barracks of Pamplona in 1517. Having established himself there as a wild and winsome soldier, he heroically led his comrades in the defense of the city against France’s siege, falling only after a cannonball shattered his right leg. With the loss of Ignatius, the city soon surrendered, and his French conquerors demonstrated their admiration for their gallant foe by bearing him with courtesy and care back to the Castle of Loyola to recover.

Ignatius’ convalescence was a prolonged and painful one—his broken leg required re-breaking and resetting on two occasions. The boisterous knight lay abed, restless and racked; and though his reading had up to that time been entirely devoted to the romantic escapades of Amadis of Gaul, El Cid, and those tomes of chivalry which broke the brain of the Knight of La Mancha, all he had at that time were two unfamiliar histories: the life of Jesus Christ and the lives of His saints. Reluctance and tedium flung obstacles in his mind, but his high-stepping imagination soon found its pace in the escapades of the heroes of the Church. Ignatius saw unfolding before him a marvelous myriad of chivalric battles and enraptured ends that put all his beloved legends to shame—or rather, gave them a purpose within a drama he had never dreamed. The Crusades were rekindled in the wounded Knight of Loyola as he vowed to rival the saints in sanctity. He swore to take Jerusalem from the hands of the heathen. His piercing eyes narrowed. He laid his naked sword over his knees and waited his day of healing.

But the fires of Ignatius’ spirit were, even then, to be redirected. As he lay upon his couch, a Lady appeared to him more resplendent than any lady of any knight errant before. Ignatius took up her favor with awe, and all concupiscence fled his body leaving him with a new vision of martial conquest. The knight would win over the world in the name of the Lady he served—the Virgin Mother of God—not through sheer militarism, but militant mysticism. As soon as he could walk, Ignatius went to the Benedictine monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat, laid his armor before an image of Mary, and then went on foot to a remote cave in the solitudes of Manresa where he spent ten months in rigid self-mortification. There in that cave, Ignatius prepared his heart for a new type of battle, training in the arms of the spirit, and strengthening his resolve to serve heaven through prayer and fasting. There in that cave, Ignatius learned the secret arts of asceticism and discovered the foundation of what would become his famous meditations, Spiritual Exercises. He emerged from the darkness of that cave and out of the dark night of his soul lean and battered, but happy—ready to march for the Holy Land.

The next two years, however, were plagued with setbacks, sickness, and severities. The Franciscans thought Ignatius a madman and refused to support his mission to take back Jerusalem. Ignatius eventually found himself in Barcelona in 1524, where he decided that, given his struggles, study was his best option. He undertook the rigors of forming his mind as rigorously as he had formed his body to be a soldier, and he who had fought and felled in fiery battles and duels, sat alongside youngsters bent over Latin books despite the mockery of men. He soon took up studies at the University of Paris, but was ever beset with difficulties arising from his street-corner, missionary zeal, such as ruffians beating him for trying to protect prostitutes and even imprisonment twice by the Inquisition on suspicion of his being a member of a heretical group.

For all of these trials, however, it was in Paris that a small group of followers gathered around the strange and striking ascetic, and he led them in doing works for the poor, in studies, and community prayer like a military officer. It was with these companions that Ignatius renewed his determination to preach in the Holy Land. Together, these seven men vowed lifelong labor as missionaries. The Society of Jesus was born. These Crusaders, the first Jesuits, then marched over the Alps toward Jerusalem, but, to their dismay, found Venice ravaged by war with the Turks. Their passage was blocked and Ignatius’ mission was foiled yet again.

They received permission to be ordained to the priesthood while in Venice, after which, they turned their footsteps toward Rome to place themselves at the disposal of the Pope. Presenting themselves to Paul III, some were charged with teaching positions, others with hospital duties, yet others with founding schools, while Ignatius drafted and expanded the official rule for his newly founded community, a task he continued for the duration of his life. The rule consisted of the usual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, but, in keeping with the military flare of Ignatius, obedience to the superior and to the pope was emphasized over the other two. Also, members were given training parallel to military training, complete with orders, drills, and a hierarchy or ranks, for Ignatius thought of his brethren as soldiers who would need the strength of discipline and the subtleties of wisdom to wage and win wars on spiritual battlefields. The Pope approved the order in 1540 and Ignatius was elected the first General Superior.

The Jesuits rapidly rose to become a power to reckon with in the Catholic Church. Their spirituality was one of unwavering faith, indomitability, and intellectual acumen. They clashed with Protestants, rescued beleaguered Catholics in England, defended the borders of France from heresy, and won over the loyalty of thousands to God and His Church. No challenge was too daunting, difficult, or dangerous, for each member of the Society wished to prove himself in daunting, difficult, and dangerous work. They marched to India, China, and Japan. They sailed to the New World. They conquered countless souls for Christ.

St. Ignatius of Loyola trained bodies and minds to better serve in the army of the Lord. His military-grade mysticism prepared, protected, and preserved the Jesuits against any foe, no matter how terrible, making St. Ignatius one of those quixotic and chivalric lunatics who refuse with an idiot determination to surrender to the ravings of a world gone mad, and thereby serve in the knighthood of heaven.

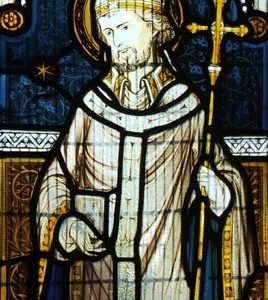

image: Zvonimir Atletic / Shutterstock.com