For roughly one thousand years, it was the Bible of Western Christendom. It was the version to which European Christians turned to compose their prayers and liturgies, that great saints consulted in their meditations, and that the greatest scholars quoted in their treatises.

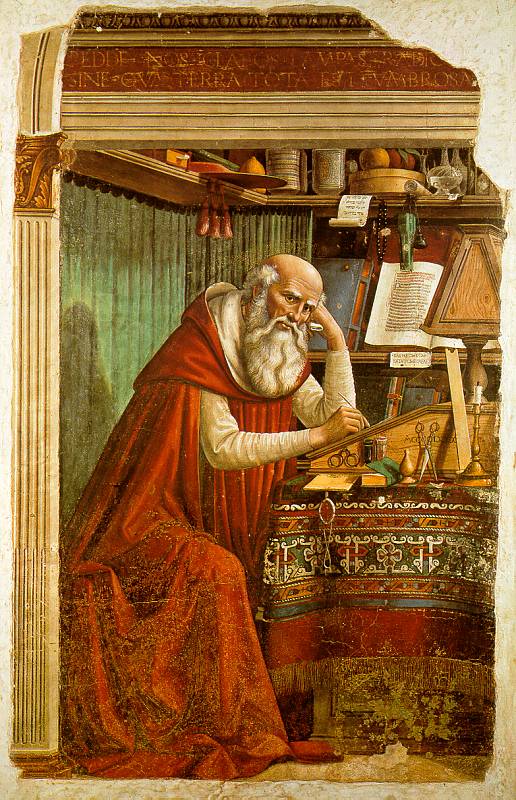

It’s harder to think of a translation of the Bible that has had more staying power than St. Jerome’s Latin version, known as the Vulgate, which was completed late in the fourth century and held sway over the Church through the Council of Trent, in the mid-1500s. Of course, the Vulgate is not the work of Jerome alone: he adopted many old Latin translations that preceded him and his own translation would be subject to later revisions. But it’s undoubtedly thanks to his theological and linguistic genius that the Vulgate endured for so long.

Few of us read the Vulgate nowadays. Yet its influence on the faith is lasting. Here are seven ways St. Jerome’s translation left an indelible mark on Christianity.

1. Full of Grace

This is what Mary was in Luke 1:28. The original Greek is quite a dense verb: kecharitōmenē, which might be most literally translated as having been filled completely with grace. St. Jerome (or the previous Latin translation he adopted) cuts right to the chase with gratia plena—full of grace—which is how Catholics have addressed Mary for centuries.

2. Born Again

Many translations of John 3:3 have Jesus telling Nicodemus one cannot enter the kingdom of God unless that person is ‘born again.’ This phrase, which has been popularized as a term for conversion by evangelicals, actually comes from the Vulgate. (In Latin the phrase is: natus fuerit denuo.) A more literal rendering of the original Greek would be ‘born from above’—as in heaven, referring obviously to a spiritual rebirth. Of course, it is also fair to say that such a person has, in a sense, been ‘born again.’

3. Baptism

One of the challenges of the Latin translator is the many Greek words for which there is no analogue in Latin. Sometimes Jerome, or his forbearers, Latinized it. Sometimes an adequate substitute was found.

Baptism is one of the Greek words apparently deemed so important that it was Latinized rather than translated. In Greek, the word is βαπτίζω, pronounced baptizó. This passed over into Latin with virtually no phonetic change: baptizo.

4. Marriage is a Sacrament

Most translations of Ephesians 5:32, which refers to the joining of a man and woman in marriage, read something like this: “This is a great mystery, but I speak in reference to Christ and the church.” (This example is from New American Bible, Rev. Ed.) It’s an accurate translation, the Vulgate opts for an alternative: “Sacramentum hoc magnum est ego autem dico in Christo et in ecclesia.” This reflects Jerome’s belief that marriage was a sacrament. Some Protestants say Jerome mistranslated the Greek word, which is mystērion, when, in fact, Jerome elsewhere did translate it as mystery. Far from being the uninformed translator anti-Catholics want to make him out to be, Jerome was making a deliberate point about the meaning of marriage.

5. Penance

Repentance is central to the Christian experience and is a recurrent theme in the gospels. For example, in Matthew 3:2, where the call to repentance is issued by John the Baptist, the underlying Greek word is a loaded term, metanoia, which implies a change in thinking. In Latin this became poenitentiam agite—do penance, reflecting the Christian conviction that true repentance is expressed in words as well as deeds. This verse had become so closely associated with the sacrament of penance that Erasmus’ attempt to change the Latin translation caused such an uproar he had to change it back. While Erasmus perhaps should be credited with seeking to recover the original sense of the Greek, which emphasized sorrow and a shift in thinking, this meaning was preserved in the original meaning of the word Jerome used, poenitentiam, which did in fact refer to regret, repentance, contrition, and a change in mind.

6. Scripture

Speaking of the proper interpretation of Scripture, this word itself is one that comes to us from the Latin. One such example is Mark 12:10, which refers to “Scripture.” But the Greek word is the deflated-sounding graphēn. Here we can be grateful that St. Jerome did not import the Greek word into his Latin translation—as he did with the verb baptize—but instead went with the perfectly suitable and more august-sounding Latin scripturam.

7. Love

It’s the greatest of theological virtues and what’s more it is what God is Himself (see 1 John 4:8). In the Greek, there any many words for love. Eros is usually associated with erotic, rapacious love. Agape, the word used in the New Testament, is self–giving love. In translating from the Greek to the Latin, Jerome had his choice of several Latin words for love. He went with caritas, preserving the non-erotic, self-giving sense of agape and helping solidify the rich concept of love that would shape Christian theology and spirituality.