Fatima’s Shepherd Girl and the Artist Monk – Part III

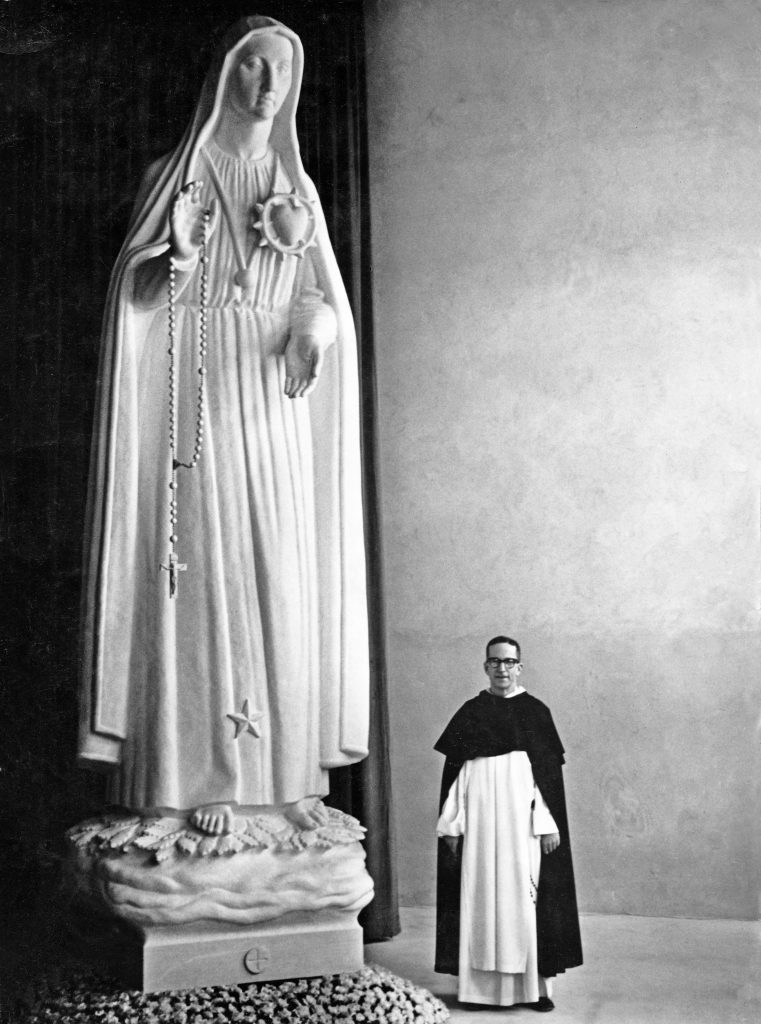

This series illustrates the making of the American statue of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Fatima, which has decorated the bell tower of the Basilica of the Rosary since 1958. In Fr. McGlynn’s statue, we see how the shepherd girl Lúcia herself saw Our Lady at Fatima. The third article follows the Dominican artist on his search for traces of the events in Fatima and lets the relatives of the visionary shepherd children speak. His report provides valuable additions and illustrations to what is already widely known.

Search for Traces in Fatima

In 1947, Sr. Lúcia lived in Vila Nova de Gaia in the north of the country. A detour to Fatima in the Serra d’Aire was the obvious choice. Like many pilgrims, the two monks visited the Dominican Monastery of Our Lady of Victory in Batalha on their way, one of the most important buildings of the high Gothic period in all Europe. For centuries, Dominican monks have gone out from there to preach the Rosary. During the persecution by Freemasons from 1910 on, the Rosary had survived in the homes of the faithful. Now the monastery, where once more than three hundred friars lived, was abandoned. Only a military post kept watch at the tomb of the ‘Unknown Soldier’ from WWI. The Eternal Light indicated that the new government had begun to restore the church to its rightful purpose. Sculptors were at work everywhere, repairing the ornaments.

The bell tower of the still unfinished Santuario de Fatima welcomes the Fathers over the hills, white and friendly against the dark sky. The large, empty niche in the tower above the main portal catches McGlynn’s eye: “What will it will contain one day?” Compared to today, Fatima must have seemed much poorer and more austere in this February of the year 1947 — a shrine of penance. When the monks arrived at the Apparition Chapel, the destination of every pilgrimage to Fatima, the great bells of the Basilica of the Rosary solemnly began to ring the Angelus.

Later, the artist expertly observed Senhor Thedim’s statue from 1920—made without Lúcia’s advice—and admired the perfect execution of the carving, its appealing loveliness and subtle pathos. The statue had escaped the Freemasons’ bomb attack on the Chapel of the Apparitions on May 6, 1922. Miracles had happened in front of this statue after acts of devotion. It had also been distinguished by the Miracle of the Dove in 1946, a common, nation-wide experience of startling magnitude and general delight, when white doves remained calmly at the foot of the statue during its journey from Bombarral to Lisbon. Over five days, they nestled in the flowers on the platform, or simply sat quite still on, or in front of, the base of the image, not to speak of their most symbolic behavior when the statue arrived at the Cathedral of Lisbon witnessed by so many thousand faithful. But the artist monk thought that one should not simply copy Senhor Thedim’s sculpture. His own image of Our Lady should be in accordance with Lúcia’s wishes.

Lúcia’s sister Teresa

Unexpectedly, an encounter with Lúcia’s sister Teresa occurs as she drives down the street on a donkey cart. Later, she visits the monks, dressed all in black with a heavy veil in the Pousada de Nossa Senhora do Rosário da Fátima, the inn. Sitting upright at the table, with dark eyes in her deep tanned, wrinkled, stern face, she gives her interview, pleasant, but also a little businesslike. McGlynn asks about miraculous signs during the apparitions. In July, she had not noticed anything like that. But on August 13, when the children were abducted, she saw petals falling from the sky like snow in the colors of the rainbow. They disappeared when people tried to catch them. In September, nothing extraordinary happened. She only heard the voices of the children.

Of course, McGlynn also asks about the miracle of the sun: Rain fell all morning on October 13. When it suddenly stopped, the sky slowly cleared up and the sun appeared without being blinding. Then it “snowed” petals again. A light as in rainbow colors played on the ground, and when people looked up, they saw the sun, which they could look into as if it were a full moon, spinning around. Even after the last apparition, she said, she still saw flowers and lights: on November 13 and in the following months. In November, she even consciously watched the ground because she thought the light created the illusion of flowers, but she still saw the flowers fall.

What did she hear? Teresa returned to August 13. Just when Jacinta and Francesco’s father had said there was no point in staying, she heard an explosion, as if a bomb had exploded under our feet. The people, she thought two or three hundred, ran to the street in panic, but then stopped, wondering what had happened, and turned back. Then, the phenomena of flowers and light appeared. Did she talk to Lúcia about the apparitions? The family never asked questions. Why not? “We saw that she did not like it, she would have run away.”

Sometimes they teased Lúcia, Teresa said: “Aren’t you the girl who saw Our Lady, and then you do things like that…” when she was singing or dancing. “What would she answer?” inquired the monk. “There is no harm in it.” The mother did not believe Lúcia until October 13th. Did she tell her about her own experience on August 13? “Ridiculous!” was the answer. “You’re all crazy!” Also on October 13, the mother did not come to the Cova because she expected to see something, but rather because she was worried that her child would be kidnapped and killed. But she saw the miracle and believed.

Rather dutifully and without any recognizable emotion, Teresa asked the monks to greet Lúcia from her. Then she went out, climbed up beside her husband on the cart, and the two drove off to their home in Ajustrel.

In the Home Village

In Lúcia’s modest birthplace, the fathers meet her sister Maria. They are welcomed with kindness. Standing at a table, Maria answers questions of the American Dominican, which Father Gardiner translates. No one from Ajustrel had come to the June apparitions, only a few from other places. As far as she knew, apart from the behavior of the children, nothing extraordinary was observed. She estimated the number of witnesses in July at one hundred. They perceived Lúcia speaking and listening, like someone having a conversation. She herself and others also heard a sound as if a bee was buzzing in a closed vessel. She had asked her sister Teresa about it, but she did not hear it. “Did you see the branches of the holm oak bending down at any time?” “No.”

In August, she did not hear an explosion like Teresa, but she ran up the slope of the Cova with the others, where the Basilica of the Rosary stands today. She heard an old man speak: “You of little faith, can’t you see that it is a miracle?” Mary also saw the rain of flowers and the phenomena that Teresa described, but also clouds around the sun that reflected different colors on the people. Some thought they had seen Our Lady in the clouds, but Maria and Teresa did not.

On August 19, the children returned from prison and led their sheep to the pasture of Valinhos. “The mother was here when Jacinta came and cried, ‘O aunt, Our Lady has reappeared’. And she showed her a branch: ‘This is the place where she put her feet’.” The mother said to Jacinta: “I thought the administrator had cleared up with all this, and now you come and tell lies.” “Was it true that the children were threatened with death?” “Yes,” Maria replied simply, adding that her mother had still said to Jacinta: “Now give me this thing and go back to Francesco and Lucia and look after the sheep!”

Skepticism and Faith

As Maria’s mother took the branch, she noticed a scent and remarked to her: “A very pleasant odor, but it’s not like roses or incense or perfume; I do not know what it is.” She put it on the table intending to ask someone else if they could recognize the scent and left the room. Later, she wanted to show the branch to others, but it was no longer there. She asked everyone, but no one had seen it, and yet she was in the house all the time. Her belief in the apparitions began on October 13, when at the Cova she sensed that same fragrance at the moment when Lúcia said: “Close your umbrellas; here comes Our Lady”. The scent remained all the while Lúcia was talking to Our Lady. Maria commented that she herself did not smell this fragrance.

Maria told the Dominicans about Lúcia’s godmother , who was also skeptical about the apparitions and worked in the fields near Valinhos on August 19. Already on the way home, she told someone that the same lights that were described on the 13th could be seen today in Valinhos. Back in Ajustrel, the mother told her what Jacinta had said. The doubting godmother was deeply moved and described what she herself had seen there.

Before coming to the matter of the October apparitions and the miracle of the sun as Maria witnessed it, McGlynn asks: “What was the practice of the family Rosary in her parental home like?” “The Rosary was customary in May and November only. When Lúcia said that Our Lady wanted the Rosary to be prayed every day, we began the daily family Rosary in October.” She then quoted the report of what Our Lady said as it was given to the crowd by Lucy after the October apparition: “Our Lord is greatly offended and we must say the Rosary every day, and we must beg his pardon”.

As a farewell gift, Maria gave the American Dominican a small piece of wood as a souvenir. It was part of a branch of the azinheira tree on which Our Lady had stood.

To Vila Nova de Gaia

There was much more to be done by way of research, Father McGlynn concluded. He wanted to interview other witnesses of the 1917 events and to take many more photos to round out a pictorial report of the places important to the story of Fatima. But he would be back from Vila Nova de Gaia after his visit to Lúcia and have plenty of time for these activities. Or so he thought… wrongly, as it turned out.

An old-fashioned cab, so old it had probably driven pilgrims to witness the Miracle of the Sun, McGlynn thought, brought the monks to the remote train station. It laboured along the level stretches and upgrades with all the speed of a bicycle. And on downgrades, even the slightest, the driver turned off the ignition to save gas. Their route took them through Vila Nova d’Ourem, the place where the children were imprisoned in August 1917 and threatened with death, then down to the valley where the train station was. Before the arrival of the Rápido, the train, the American monk saw an azinheira tree across the tracks. He had seen none at the Cova or during his walks.

Week before, he had spent many hours in the highly respected Botany Department of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, founded in 1764, the seventh-oldest institution of research and higher education in the United States, trying to track down a specimen of the tree. He wanted to have the proper type of leaf beneath the feet of the statue; but he had failed to arrive at certainty. So he plucked a branch of the tree at the train station to show it to Lucia for verification.

True to its name, the Rápido sped along comfortably over the distance of about two hundred miles to Oporto through the rolling country that was dotted with vineyards. Finally the train moved across the Douro River with the caution of a tightrope walker, on a single-track span that seemed 200 feet from the water. Before the two Dominicans, on the left, the city of Oporto, crowded with tier upon tier of tightly packed buildings, covered the cliff-like bank. On the right, terraced gardens and vineyards with tall, narrow homes in many colors cut up the steep bank in a picturesque pattern of steps. Full-beamed sailboats with high prows and square sails plied the river.

Arriving at the Dorothean Sisters

Vila Nova de Gaia is across the river from Oporto, a smaller city, mostly residential. Here, Lúcia spent several years after fleeing from the Spanish communists. The rain beat heavily on the two monks as they stood, ringing over and over a bell at the side of the impenetrable iron plates of the Colégio do Coraçao Sagrado de Jesus do Sardão, an ocher building with a red roof, rather long and plain looking. A little nun, flurried with apologies, finally led then in. “Today, on this February 6, is the Feast of Santa Dorothea,” she explained. All the Dorothean Sisters were at choir in a remote part of the building.

Finally at his destination and relieved from his wet hat and topcoat, Father McGlynn pondered in the visitors’ room how to display his statue. He took the model of the statue from the box and tried here and there, it in various locations. It did not show to advantage anywhere, he thought. The window frames were low and gave unflattering light from beneath; and in every conceivable spot in the room, it had to compete with many more conspicuous objects. Finally, he gave up trying and rested it besides a lamp. When a nun appeared in the doorway, he thought for a moment it was Lúcia, before he realized that her face was older than Lúcia’s could be. It was the mother provincial of the Dorothean sisters in Portugal and Spain, a “lovely little lady”, as McGlynn notes, who entered. The bishop had telephoned the day before to say that two Dominican fathers from the United States were coming. Father Gardiner pretended to be indignant at this slight of his nationality – he was Irish; then he explained the connection.

✠

Editor’s note: Editorial assistance was kindly provided by Jane Stannus, a journalist and translator. She is a regular contributor to The Spectator USA. Her work has also appeared in Crisis Magazine, the Catholic Herald, Critic Magazine and the National Catholic Reporter.

This article is the first part in a weekly series on the art of Fr. McGlynn and the work of Our Lady of Fatima. Check back each Friday for more info about how Our Lady of Fatima inspired an artist at her shrine. You can read the first article here or see the ongoing series page here.

Sources and quotations for this include the book by Sr. Lucía dos Santos, Fatima in Lucia’s own Words. As well, quotations and the story of Fr. McGlynn can be found in the book, Vision of Fatima, which is available through Sophia Institute Press.

Photo by Portuguese Gravity on Unsplash