Picture the scene: you’ve just arrived in heaven, after probably passing through purgatory.

Tradition tells us that you are then invited to the beatific vision. The Book of Revelation adds some details to this, listing some of the things you will receive in heaven. They include the ‘hidden manna,’ a victory crown, and fruit of the tree of life. But one item seems out of place in the list: a white stone with a name on it.

Here is how it is described in Revelation 2:17,

‘“Whoever has ears ought to hear what the Spirit says to the churches. To the victor I shall give some of the hidden manna; I shall also give a white amulet upon which is inscribed a new name, which no one knows except the one who receives it.”’

What is the meaning of this white stone or amulet? Our curiosity is heightened by the fact that it has a new name which is known only to those who receive it. The other prizes are familiar to us. The hidden manna refers to our Eucharistic communion with Christ. The victory crown refers to our conquest over sin, Satan, and death through Christ. And the tree of life makes sense if we remember that heaven is Eden restored.

But a white stone?

There are a number of theories explaining what this means—and they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. In the first place, it should be pointed out that the white stone, contrary to what we might expect, really does come hand in hand with the hidden manna. The Old Testament actually describes the manna as having a white appearance and one account likens it to a precious stone (see Exodus 16:31 and Numbers 11:7).

Moreover, according to ancient Jewish tradition, precious stones and pearls rained down from heaven along with the manna. Precious stones also adorned the vestments for priests in ancient Israel. The connection the precious stones suggest between manna and priestly vestments makes sense if we remember that the manna is a type of the Eucharist, the body of Christ, the perfect priest who sacrificed Himself for us.

As for the white stones, one explanation is that they symbolized someone’s innocence at the conclusion of a trial—the white color, suggesting purity, reinforces this association. White stones were also awarded to victorious gladiators, which fits in with the context, which is about Christians who are victorious over idolatry. In addition, white stones served as a sort of ancient form of a ticket to a banquet, which ties in with the theme of the hidden manna.

The secret name on the stone could be a reference to the ancient practice of making magical amulets by inscribing the secret name of some deity on it, empowering the person who possessed the stone and recognized the name. Again, translated in Christian terms, we can see the white stone as a sacramental that empowers the one who holds it through knowledge of Christ’s name. (I’m particularly indebted for these insights to the commentaries by Robert Mounce, Brian Blount, Charles John Ellicott, and G.K. Beale, this author’s father.)

In the ancient world, the name of God signified His being. The classic example is God’s self-revelation of His name as I am to Moses: God is one who is self-existent in His being. In receiving Christ’s name His followers thus encounter his very being. As Beale explains,

In the ancient world and the OT, to know someone’s name, especially that of God, often meant to enter into an intimate relationship with that person and to share in that person’s character or power. … When someone gave a name to another person or thing it meant that they possessed that person or thing (Beale, 254).

So Christians will possess Christ in his very being because He possesses them. This leads to an alternative interpretation of the new secret name—that it is the new name of the individual Christian. The saints take on the name of Christ. This is consistent with Revelation 3:12, where Christ announces that He will inscribe His name on that of the believers, as Blount points out.

There is a long tradition of this in the Bible, stretching from Abram-Abraham in the Old Testament to Saul-Paul in the New, as Ellicott notes. Here, the new name signifies the final ‘transformation’ of the Christian, according to Mounce:

The new name is more likely to be the name of the one who overcomes. No one else can know the transforming experience of fidelity in trial and the joy of entrance to the great marriage supper of the Lamb. The overcomer’s name is new … in quality; it is appropriate to the New Age (Mounce, 83).

In heaven, then, Christians are promised to arrive at a fuller knowledge of Christ that ‘transforms’ their own identity. As the catechism says, “To live in heaven is ‘to be with Christ.’ The elect live ‘in Christ,’ but they retain, or rather find, their true identity, their own name.”

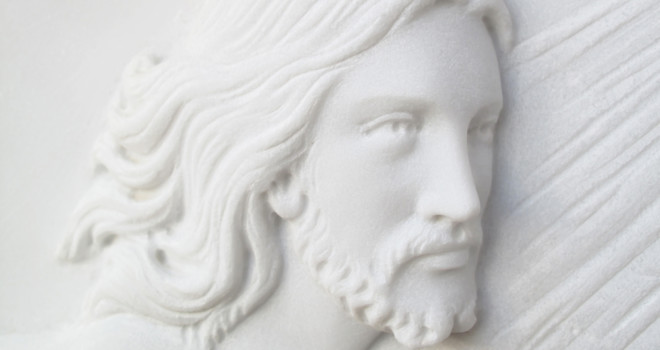

The symbolism of the white stone is consistent with the Incarnational character of Catholic Christianity, which has always been concerned with the ‘thickness of the sensible,’ as one Catholic philosopher puts it. We believe in a God who became a flesh-and-blood man and who is ‘in heaven’ in physical form. We ‘taste and see’ the goodness of God in the Eucharist. We believe in the resurrection of the body.

The white stone is something that can be seen and grasped—a visible token of the invisible reality of the saints’ friendship with Christ and their invitation to the victory banquet in heaven. May we all pray that there is a white stone with our name on it waiting for us in heaven.

✠