It was hard to listen to Cicely Tyson talk about her life without recognizing the strong undercurrent of Christian faith in her words, deeds and also in her art. While remaining a proud, private, dignified woman, her faith was not something that she tried to hide.

The question here at GetReligion, of course, was whether any of that imagery and information would make it into the news coverage surrounding her death at the age of 96.

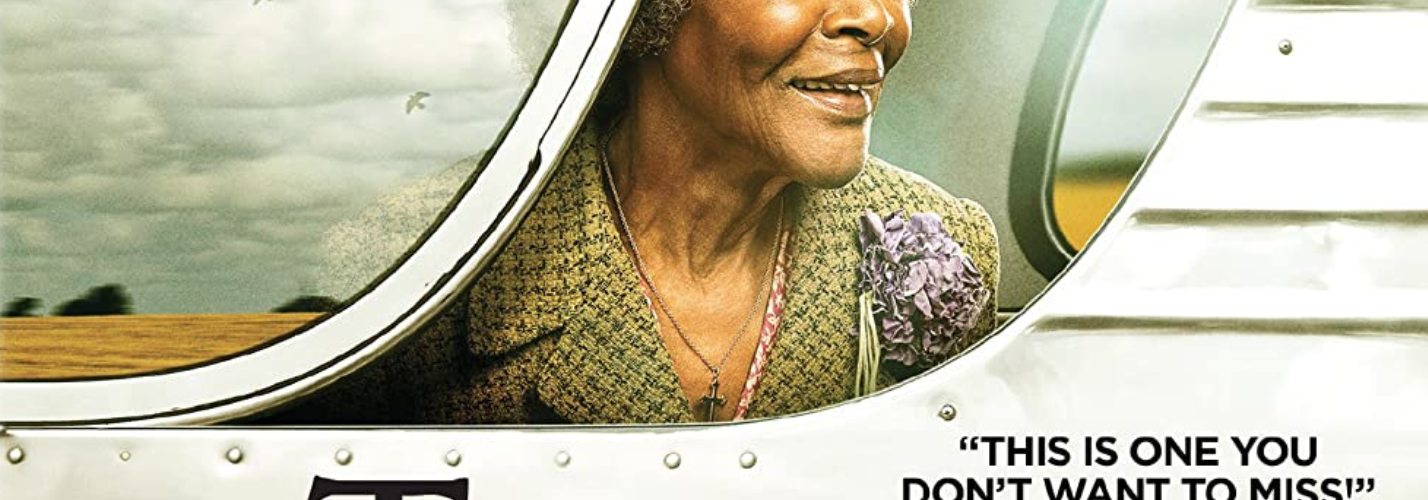

The answer was, of course, “yes” and “no.” Many of the obituaries mentioned her Tony-winning return to Broadway in 2013, at the age of 88, to play the unstoppable matriarch in Horton Foote’s classic, faith-driven play, “The Trip to Bountiful.” The show-stopping moment, night after night, was when Tyson would sing — joined by many in the audience — the classic hymn “Blessed Assurance.” It’s hard to avoid the content of lyrics such as these:

Blessed assurance, Jesus is mine; Oh, what a foretaste of glory divine!

Heir of salvation, purchase of God; Born of His Spirit, washed in His blood.This is my story, this is my song, Praising my Savior all the day long.

If you were looking for the faith-free version of Tyson’s life, the natural place to turn was The New York Times.

This story did a great job of capturing her impact on American culture, especially in terms of the sacrifices she made to portray African-American life with style, power and dignity. Here are two crucial summary paragraphs on that essential theme:

In a remarkable career of seven decades, Ms. Tyson broke ground for serious Black actors by refusing to take parts that demeaned Black people. She urged Black colleagues to do the same, and often went without work. She was critical of films and television programs that cast Black characters as criminal, servile or immoral, and insisted that African-Americans, even if poor or downtrodden, should be portrayed with dignity.

Her chiseled face and willowy frame, striking even in her 90s, became familiar to millions in more than 100 film, television and stage roles, including some that had traditionally been given only to white actors. She won three Emmys and many awards from civil rights and women’s groups, and at 88 became the oldest person to win a Tony, for her 2013 Broadway role in a revival of Horton Foote’s “The Trip to Bountiful.”

But the only reference to her Christian faith — negative, of course — came in this bite of biography:

Cicely Tyson was born in East Harlem on Dec. 19, 1924, the youngest of three children of William and Theodosia (also known as Frederica) Tyson, immigrants from the Caribbean island of Nevis. Her father was a carpenter and painter, and her mother was a domestic worker. Her parents separated when she was 10, and the children were raised by a strict Christian mother who did not permit movies or dates.

The Times also offered an “appraisal” of Tyson’s career with this striking headline: “Cicely Tyson Kept It Together So We Didn’t Fall Apart.”

Is it just me, or is something rather obvious missing from this passage at the end of the piece?

Tyson knew her place. It was in our movie palaces and living rooms, but also at Black families’ kitchen and dining room tables, an emblem of her race, a vessel through whom an entire grotesque entertainment history ceased to pass because she dammed it off; so that — in her loveliness, grace, rectitude and resolve — she could dare to forge an alternative. She walked with her head high, her chest out, her shoulders back as if she were carrying quite a load that never seemed to trouble her because she knew she was carrying us.

Yes, Black families have been known to gather in pews, as well as kitchen and dining room tables. That was certainly part of Tyson’s story.

The New York Times is important, of course, but it is even more important that the Associated Press served up three stories about Tyson’s life, career and cultural impact without a single reference to her Christian faith (other than a fleeting reference to God in a Michelle Obama tribute quotation). These are the stories that would appear in the vast majority of American newspapers.

Don’t believe me? Click here (care of PBS) for the main obituary, here for a collection of tribute quotes and here for a background feature, with more details about her history. The latter contained this amazingly tone-deaf passage:

A new generation of moviegoers saw her in the 2011 hit “The Help.” More recently, she was seen on TV in a recurring role on “How to Get Away with Murder,” which starred Davis. And in roles in Tyler Perry films — ”Diary of a Mad Black Woman″ and “Madea’s Family Reunion” —- her character gave sage advice on forgiveness and living with integrity.

Uh, “sage advice”? Cue up those speeches in the Perry films and you’ll see that they are drenched in God-talk and references to faith.

Here’s another reason that it was hard to avoid the faith-element in the Tyson story. Just before her death, she released a memoir entitled “Just As I Am” — yet another example of her using a Gospel hymn as a frame for her life and work.

What did she have to say about dying?

“ … I don’t know when my day is coming. None of us does. Which is why, as soon as my lids slide open each morning, I say thank you. Thank you, Father, for the gift of another day. Thank you for just one more breath. Thank you for the sacred opportunity to live this life. …

“The way I see it, God isn’t finished with me. And when I’ve completed my job, he’ll take me. Until then, I’ve got plenty to do. …”

Now, I am happy to note that the Los Angeles Times package about Tyson did a much better job of weaving her own words into its multi-story package about her death.

This started with the overture of the main obituary:

Cicely Tyson, actress who captured the power and grace of Black women in America, dies

When Cicely Tyson accepted an Emmy in 1974 for her starring role in “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,” she smiled into the camera and spoke straight to her mother: “You see, Mom,” she said, “it wasn’t really a den of iniquity after all.”

Some two decades earlier, the sternly religious Theodosia Tyson had thrown her daughter out of her New York City home for getting into the “sinful” entertainment business. For two years, they didn’t see each other.

Only much later did Theodosia acknowledge that her daughter, who by then was famous for the disciplined and elegant quality of her acting, had chosen superbly. Tyson worked less often than she could have because of her insistence that roles for Black women reflect a sense of power and grace.

The biography section included this bit of Tyson-speak:

When she wasn’t in school, she was in church “from Sunday morning till Saturday night,” she once said. “I recited. I played the piano. I sang in the choir. I taught Sunday school…. We went to prayer meeting Monday nights, children’s meeting, grown-ups’ meeting Wednesday, old folks’ meeting Thursday, and Saturday we cleaned the church.”

Sure enough, the hymn “Blessed Assurance” made its way into this fine story, but with an added biographical reference that gave that Broadway moment even more power:

Tyson’s performance was moving in many ways. At one point in the second act, her character rises off a bus station bench and sings the hymn “Blessed Assurance.” Audience members — many of whom were Black and said they sang as children in church — would invariably join in. It was a phenomenon that, according to the New York Times, may have been unprecedented on Broadway.

Tyson had been taken with the hymn for years. In Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, a pew bore a plaque she donated: “To Mother,” it said. “Blessed Assurance.”

Top that.

In terms of basic journalism, the question here is quite simple: Why avoid the role of Christian faith in the life and work of a woman who made it perfectly clear that this was a crucial part of her story? How does the omission of this material strengthen the coverage?

Just asking.