If you’re into sports, you know that the National Football League player draft took place a few days ago. And if you’re into football — college or professional — you know that the name called as the first pick in this draft was a foregone conclusion.

The Jacksonville Jaguars won the race to the bottom of the 2020 standings, which allowed them to select one of the most highly rated quarterback prospects ever — Trevor Lawrence of Clemson, a 6-foot-6, 220-pound superstar who lost a total of two games in college.

The assumption was that Lawrence had everything that any NFL executive or coach would want.

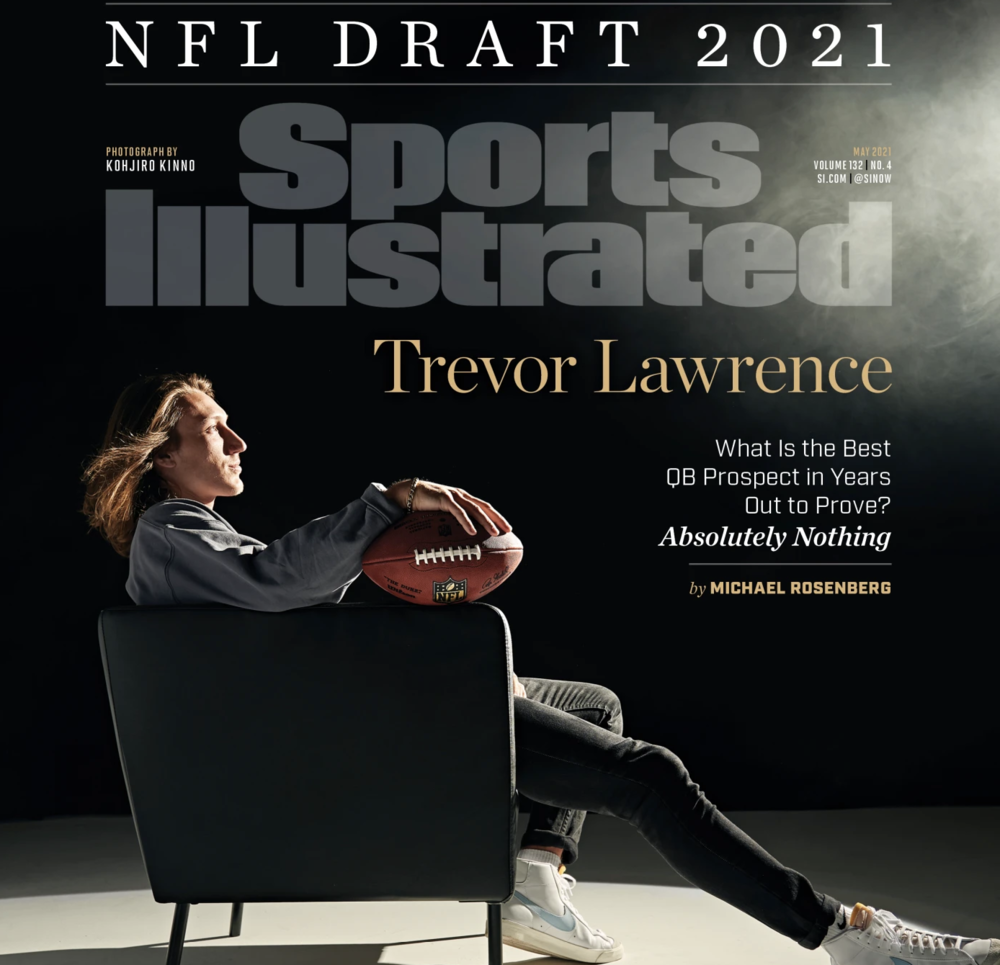

Then again, maybe not. Shortly before the crowning ceremony, Sports Illustrated published an eyebrow-raising feature on the quarterback with this double-decker headline:

The Unrivaled Arrival of Trevor Lawrence

The best quarterback to come into the draft in nearly a decade, Lawrence will enter the NFL with the billing of a generational signal-caller, a keen sense of self and a burning desire to prove absolutely nothing.

Now, what did that final phrase mean, the statement that Lawrence had a “burning desire to prove absolutely nothing”?

Maybe it had something to do with his father saying that he told his gifted son: “God has given you a great gift. But you know, at some point when the game’s taken more from you than it’s giving to you, you need to step away.” Or maybe it was this statement by his high-school coach in Georgia: “[Trevor] will play as long as God wants him to.”

Clearly religious faith was a problematic part of this young man’s mental and emotional make-up. As Christian scribes John Stonestreet and Roberto Rivera asked, in a BreakPoint radio commentary: “Does Trevor Lawrence Have Too Much Character to be the NFL’s #1 Pick?” Here is a key chunk of that:

As a committed Christian, who is very public about his faith and the way it shapes his life, one of the things Lawrence considers more important than football is Jesus. He also apparently has a thing for family. Recently, Lawrence skipped an NFL pre-draft event to marry his high-school sweetheart. This crazy behavior fed a narrative that Lawrence, like other Christian athletes, is probably too “soft” and lacks the kind of monomaniacal focus required to succeed in football.

Given that there’s never been a shortage of Christian players who possessed deep faith and achieved great on-field success, this narrative is baseless. No one who was the receiving end of a hit by Steelers’ great Troy Polamalu thought his faith made him somehow “soft.”

Clearly, there was something different about Lawrence and his family, including Marissa Mowry, the young woman (his sweetheart since junior high) who is now his wife.

But the key to this strange equation is the perception that an NFL quarterback is supposed to be wired in a certain way.

Here’s the SI thesis statement:

The NFL is a league for the obsessive and the petty, so much so that fans can identify most star quarterbacks by their slights: 199th pick in the draft; passed over by his hometown 49ers; told he should switch to receiver even after he won the Heisman as a quarterback; drafted behind Mitchell Trubisky. This is the league of Bill Parcells’s saying, “This is not a game for the most well-adjusted people”; of Baker Mayfield’s taking offense when his old Browns coach, Hue Jackson, took another job after Jackson was fired; of defensive backs Richard Sherman and Darrelle Revis’s feuding long after Revis retired. And now it is the league of Trevor Lawrence’s saying, “It’s not like I need this for my life to be O.K.”

The bottom line: Is Lawrence making a statement about his view of football or is he making a statement about the high priority of faith and family in his life?

To see how some critics are interpreting all of this, see the following at ESPN: “Quarterback Trevor Lawrence addresses criticism over his quotes about his motivation.”

The SI cover story, late in the text, does discuss the quarterback’s Christian faith — but only after the entire piece is framed in terms of questions about his attitude and drive. Here is a key passage early on, in which Lawrence stresses that he does want to be “the best I can be” and to “maximize my potential.” Read this next part carefully:

Lawrence is only 21. He finished Cartersville (Ga.) High three years ago and still peppers his sentences with like. But he lacks that youthful desire to conquer the world.

“It’s hard to explain that because I want people to know that I’m passionate about what I do and it’s really important to me, but . . . I don’t have this huge chip on my shoulder, that everyone’s out to get me and I’m trying to prove everybody wrong,” he says. “I just don’t have that. I can’t manufacture that. I don’t want to.” Marissa adds, “There’s also more in life than playing football.”

“Yeah,” Trevor says. “And I think people mistake that for being a competitor. . . . I think that’s unhealthy to a certain extent, just always thinking that you’ve got to prove somebody wrong, you’ve got to do more, you’ve got to be better.”

Marissa: “That usually only leads to sadness as well — always, like, striving for something new or better.”

I have a lot of confidence in my work ethic, I love to grind and to chase my goals. You can ask anyone who has been in my life. That being said, I am secure in who I am, and what I believe. I don’t need football to make me feel worthy as a person. I purely love the game and (2/3)

— Trevor Lawrence (@Trevorlawrencee) April 17, 2021

The short section of the story that discusses the quarterback’s faith seeks to contrast Lawrence with his older brother, Chase — an artist who is open about the years in his life when he doubted and strayed.

That leads to this passage:

[Chase] has since sobered up and devoted himself to Christianity, but he remains a questioner. He and Trevor discuss religion frequently, and both understand that part of being devout means asking why.

“I got to a point to where it really just wasn’t enough for me to like, blindly follow something,” Trevor says. “I have to understand it a little bit. And that’s where we’re at now. We’re just always having good conversations. … I’m in my 20s, I’m getting older, kind of transitioning into adulthood, and now it’s like, O.K., ‘What’s really important to me? What do I believe?’ ”

Football is not religion, of course, but there are similarities in Trevor’s approach to both. He is a passionate believer, but on his terms.

OK, I’ll ask: What do they discuss?

Do they discuss topics that are actually linked to the article’s core discussions of the definition of success and the parts of life that are more important than football? Maybe there is content in these discussions about the parts of life that Lawrence “needs” more than success in athletics?

There’s no way to know, since the SI team doesn’t get into that. This next passage is the closest the article comes to responding to the earlier thesis statement:

The sports world is teeming with people who use religion out of convenience. Lawrence vows never to sign an eight-figure contract and call it “God’s plan.” That is narcissism cloaked in religion. He will also enjoy the sport because he has always enjoyed the sport, not to prove his worth to some TV pundit. Lawrence will be the Christian he wants to be and the football player he wants to be. He will decide what he is getting out of his Sundays.

I found myself asking a few basic journalism questions, such as: Does the Lawrence family attend a specific church, maybe one that has a pastor who knows them pretty well? Was there a pastor who played a key role in the life of Trevor Lawrence who could, you know, be interviewed?

As you would expect, these questions are “religious” or even “conservative.” Thus, news consumers need to seek answers in the Baptist Press piece that ran with this headline: “The community that helped build Trevor Lawrence.”

The lede on that post noted: “Trevor Lawrence isn’t your typical 21-year-old, but he was a fairly normal church kid.”

The key here, as anyone knows who has heard a sideline interview with Trevor Lawrence, is that Christian faith is a crucial element of his story and his worldview. It’s part of his “sense of self” and he isn’t reluctant to discuss that.

That being the case, why was SI so reluctant to put this man’s faith higher in the story? Why not ask the obvious religious questions and, thus, include some essential facts about his life? Does he have the wrong kind of beliefs?

Just asking.

FIRST IMAGE: Posted on the Instagram account of Marrisa Lawrence.

MAIN IMAGE: Also from the Instagram account of Marrisa Lawrence.