THE QUESTION:

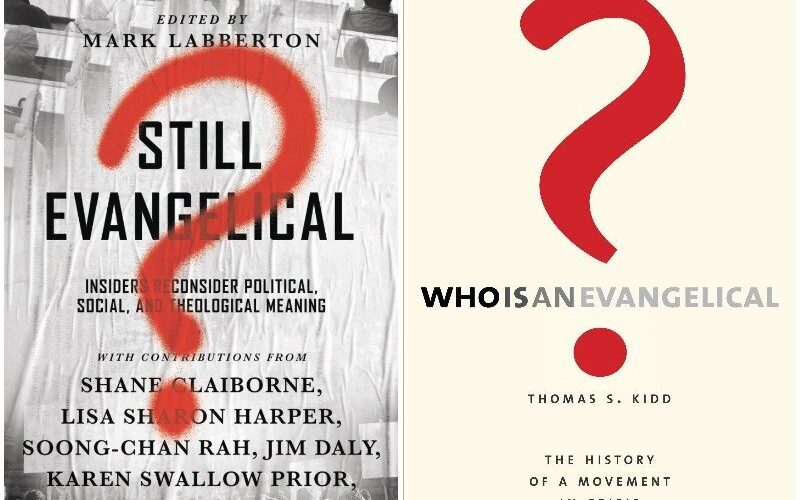

One more time: What is an “evangelical”?

THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

Last month the Public Religion Research Institute reported that its latest polling shows white U.S. Protestants who identify as “evangelical” are now outnumbered by whites who do not do so. That upended the usual thinking on numbers, and analysts raised doubts. The discussion led Terry Shoemaker of Arizona State University, writing for theconversaation.com, to again mull the perennial question of what “evangelical” means.

In the American context, this term essentially covers the conservative wing of Protestantism, a variegated constellation of denominations, independent congregations, “parachurch” ministries, media outlets, and individual personalities that is organizationally scattered but religiously coherent.

There are three ways of defining and counting U.S. evangelicals — by belief, by church affiliation and by self-identification. Shoemaker’s analysis (which is open to some nitpicking) started from the belief aspect and a four-point definition by historian David Bebbington in his 1989 work “Evangelicalism in Modern Britain.” In summary, these points are:

(1) a high view of the Bible as Christians’ ultimate authority,

(2) emphasis on Jesus Christ’s work of salvation on the cross,

(3) the necessity of conscious personal faith commitments and changed lives (often called the “born again” experience) and

(4) activism in person-to-person evangelism, missions and moral reform.

Problem is, those four points overlap with the definition of “Protestant” or even “Christian.”

A 2015 definition from America’s National Association of Evangelicals sharpens the line against liberalism by asserting that “only those who trust in Jesus Christ alone as their Savior receive God’s free gift of eternal salvation.” On point one, many evangelicals would specify belief in the Bible as “verbally” inspired by God, or “inerrant” on history, or interpreted “literally” when that’s what the text signifies.

The Religion Guy would add another criterion: firmly planted doctrinal and moral traditionalism. Today, for example, evangelicals are distinguished from “mainline” or “liberal” Protestantism by opposition to same-sex relationships. On doctrine, “Oneness” or “Jesus Only” Pentecostals appear evangelical but do not qualify because they reject Christianity’s historic doctrine of the Trinity, that the one God exists eternally in three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Polls by the Southern Baptist Convention’s Lifeway Research show that “evangelicals by belief” were 19% of the U.S. adult population in 2016, 20% in 2018, and 18% last year. However, a prior study found that only 59% of those who identified as evangelicals agreed “strongly” with central tenets.

In addition to belief, evangelicals can be defined through polls that carefully ask respondents what specific congregation they belong to and then checking what national body it is part of. This approach is used by the General Social Survey, Association of Religion Data Archives, and the Pew Research Center in its important Religious Landscape Study of 2014. On the basis of affiliation, Pew calculated that 25% of Americans belong to evangelical churches, making this the nation’s largest religious bloc.

Pew follows an elaborate table of hundreds of church groups from InfoGroup that classified the Protestant groups as either “evangelical,” “mainline,” or “historically black.”

Take the “Presbyterian/Reformed” listing. Polls about “Presbyterians” that don’t specify which group are virtually meaningless. There’s one black denomination, and four considered “mainline,” while “evangelicals” are scattered across — we’ll skip the full names — the ARP, BPC, CRCNA, CCCC, CPC, EPC, FRCNA, OPC, PCA, PRC, RCUSA, RPCNA, and URC. The Guy would add COEP, NRC and, soon, ARC.

In addition, the evangelicals form a distinctive minority subgroup within pluralistic “mainline” church bodies. The large United Methodist Church is 34% evangelical, according to Cooperative Election Study data analyzed by political scientist Ryan Burge. Not only that, CES indicates 18 percent of Catholics self-identify as evangelical. And “evangelical” often means simply “Protestant” in Europe so that, for example, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America with its European roots carries an “evangelical” name but today is correctly categorized as “mainline.”

Further complexities. “Historically black” Protestant denominations contain many evangelicals in belief but are usually considered a totally separate category and generally do not use that label for themselves.

CONTINUE READING: “What is an ‘evangelical’?”, by Richard Ostling.