I like the idea of being a descendant of the Northumberland Percys because they were recusants and a couple of them lost their heads as martyrs.

~ Walker Percy

“If it does not please you to serve the LORD,” Joshua tells the Israelites in Sunday’s first reading, “decide today whom you will serve…. As for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.” Note that Joshua’s affirmation of loyalty to the God of Israel is not a declaration of personal preference, but a summation of his clan’s corporate identity. He’s announcing that he and his family (and, ultimately, his people) consider fidelity to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to be essential to who they are, and that nothing – not even the prospect of annihilation at the hands of the Canaanites – can make them budge.

A similar stubborn fealty is on display at the end of today’s Gospel. Jesus had just finished his bread of life discourse with a startling twofold proposal: First, that he himself was the new manna, and that, second, everyone should partake of his lifegiving flesh. “Do you also want to leave?” the Lord asks his disciples after most of the rest of the crowd, alarmed by Jesus’ words, had split. “Master, to whom shall we go?” St. Peter flatly states on behalf of the Twelve. “We have come to believe and are convinced that you are the Holy One of God” (Jn 6.67-69).

As we now know well, Peter and the apostolic band will come to pay dearly for that conviction. They were hunted down, tortured, and martyred in a variety of grisly ways, but their belief in Jesus stood firm because they’d known him, they’d been with him for years, they saw what happened on Calvary, and yet they’d encountered him — alive!

“That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands,” St. John relates on behalf of his confreres, “we proclaim also to you” (I Jn 1.1, 3). That unshakable faith, combined with extraordinary outpourings of grace, gave the Apostles courage – as a group, as a band, as an ecclesial brotherhood — to remain ambassadors of the Gospel and steadfast witnesses to Christ until their last breaths were taken from them.

It’s the same kind of tenacious communal commitment to the Lord that we glimpse in the heroic legacy of the Percys during the English Reformation. The elder Sir Thomas Percy participated the Pilgrimage of Grace uprising against Henry VIII following the King’s repudiation of Papal authority, his suppression of the monasteries, and other royal anti-Catholic actions. After Percy’s conviction for treason, he was drawn and quartered at Tyburn in 1537, and is “considered a martyr by many” according to the Catholic Encyclopedia.

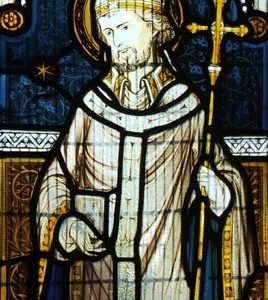

Bl. Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland

Because of Percy’s crimes, his young sons, Thomas and Henry, were estranged from their noble privileges, but they were rehabilitated in 1549. The Catholic Queen Mary restored the Earldom of Northumberland to the younger Thomas in 1557, citing his “noble descent, constancy, and virtue, and value in arms.” Six years later, despite misgivings regarding Thomas’s likely Catholic sympathies, the Protestant Elizabeth I bestowed on him the Order of the Garter.

In time, however, Queen Elizabeth’s persecution of those loyal to the Pope and the old Faith grew too much for Thomas, and he took a leadership role in the 1569 Rising of the North, an effort to seat Mary, Queen of Scots, on the English throne. The effort failed, and Thomas, like his father, was captured, tried, and convicted of treason. Although offered a commutation of his death sentence in exchange for a renunciation of his religion, Thomas refused and was beheaded in 1572. Pope Leo XIII declared Thomas Percy a martyr and beatified him in 1895, and his feast is ordinarily observed on August 26.

Before his death, Bl. Thomas’s final words summed up his organic, integrated vision of family and faith: “I am a Percy in life and in death” – that is, just as his bloodline couldn’t make him anything other than a Percy, his convictions couldn’t make him anything other than Catholic, and if that meant the chopping block, then so be it.

Percy’s ultimate witness to the Faith, like so many of the lay English martyrs, is especially instructive today. With the sole exception of St. John Fisher, all the English bishops had previously given in to Henry VIII’s schismatic demands, as did many of the clergy. Faithful lay Catholics like Thomas Percy and his kin were spiritually on the lam with little or no support from the hierarchy or institutional Church. Intrepid Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries managed to administer them the sacraments from time to time, but even that was hit and miss – more often, miss. And so, you have to wonder: What kept folks like Percy going? Why’d they stay Catholic? Why didn’t they just give in, take the path of least resistance, and conform?

Frank Sheed provides a ready answer. “Institutional Israel, the Chosen People, as the Prophets show it, was even worse than the harshest critics think the Catholic Church: yet it never occurred to the holiest of the Jews to leave it,” Sheed writes in Christ in Eclipse (1978). “They knew that however evilly the administration behaved, Israel was still the people of God. So with the Church: an administration is necessary if the Church is to function, but Christ is the whole point of the functioning.” Sheed continues, and it’s noteworthy that he refers back to the English Reformation for an object lesson:

We are not baptized into the hierarchy, do not receive the cardinals sacramentally, will not spend eternity in the beatific vision of the pope. St. John Fisher could say in a public sermon, “If the pope will not reform the Curia, God will”: a couple years later he laid his head on Henry VIII’s block for papal supremacy, followed to the same block by Thomas More, who had spent his youth under the Borgia pope, Alexander VI, lived his early manhood under the Medici pope, Leo X, and died for papal supremacy under Clement VII, as time-serving a pope as Rome had had.

St. Thomas More, in other words, was in the same boat as Bl. Thomas Percy: both had been lay heads of household who were compelled to defend the Faith with their lives in the face of a full-out episcopal abandonment. No doubt many thought the two men foolish, irresponsible, and utterly selfish. Many would’ve argued that, given the apparent perfidy of the bishops, More and Percy could’ve felt justified in cutting corners of conscience in order to survive.

But they could not, for their Catholic identity was not subject to deliberation, dilution, or dissembling. Here, again, I think Sheed captures the nub of what might’ve been in the minds and hearts of lay martyrs like Percy and More, and he is worth quoting at length:

Christ is the point. I myself admire the present pope, Paul VI; but even if I criticized him as harshly as some do, even if his successor proved to be as bad as some of those who have gone before, even if I sometimes find the Church as I have to live in it a pain in the neck, I should still say that nothing a pope could do or say would make me wish to leave the Church, though I might well wish the he would. Israel, through its best periods as through its worst, preserved the truth of God’s Oneness in a world swarming with gods and the sense of God’s majesty in a world sick with its own pride. So with the Church. Under the worst administration – say as bad as John XII’s a thousand years ago – we could still learn Christ’s truth, receive his life in the sacraments, and be in union with him to the limit of our willingness. In awareness of Christ, I can know the Church as his Mystical Body. And we must not make our judgment by the neck’s sensitivity to pain!

A distant relation of the Tudor Percys distills Sheed’s insights into a single line: “When it is asked just so, straight out, just so: ‘Why are you a Catholic?’” writes Catholic writer Walker Percy, “I usually reply, ‘What else is there?’” It’s as if, in the midst of tumult, disillusionment, and shame, that latter-day Percy is reminding us of the extemporaneous insight of the Fisherman and first pope: “To whom [else] shall we go?” And we pray, like Bl. Thomas Percy and St. Thomas More, that we all might meet with fortitude the consequences of adopting that insight as our own.