Every sort of work leads to realization, to completion. Completion means rest. So all work leads to some rest.

In connection with this truth we notice two tendencies at present. On the one hand, we observe the myth of work, the fever, the deification of work, the attempt to raise it to the highest dignity, to a virtue, to sanctity almost. This tendency and its accompanying propaganda have brought about a state of affairs where man is so schooled in continual effort that he is almost afraid of rest. Workers, grown unaccustomed to a day of rest because their employers so often exploited them, do not know what to do with a day off, and actually feel ill at ease. The long-standing compulsion to work has increased to such a degree that it has taken from man his longing for rest and created in him a fever of external activity.

This is one trend: the drive to get the greatest possible output, “the record” — that new motto for workers.

The second tendency, which runs parallel to the first, is the arrangement of life so that man may work as short a time as possible — two, three, five hours only — so as to free him from work and replace him by a machine.

God’s thought long ago reconciled and solved both these tendencies by the divine law: “Six days shalt thou labor, and shalt do all thy works. But the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord” (Exod. 20:9-10).

A rest! That is to say, a break in work, a holy rest directed toward the Lord. And therefore this rest should have certain religious features.

The workday must achieve two goals

It is possible to limit the duration of work according to the goal of our daily toil. What is this goal?

Daily work should be of such a kind as to ensure the greatest material and economic efficiency and to justify man’s right to a fair wage. In short, there must be a result, the concrete value of this work. And this is the first task of the day. This is the fruit of work, justice in the purely temporal order, in the name of which we can say, “Give us this day our daily bread.”

And the second task of the day? Today’s work ought to be such as to contribute to the normal development of man’s abilities and personal powers. Why? Because man must strive continually to perfect his powers of reason and will, from which he cannot take a vacation. It is necessary that there be continuity in the work of our spiritual powers.

Time for more important tasks

Prudence and justice command man to refrain from the sort of work that would exhaust his strength completely, for work is not the most important task; it is not the only duty in the day, or in life, either.

The day’s work should be of such a kind that one is able, with the strength left over, to fulfill the other daily tasks of life. A man coming from work should still have the wish and the energy to work at other things. He should still have some time, as well as physical and spiritual strength.

Rerum Novarum defines this in the following manner: “Daily labor, therefore, must be so regulated that it may not be protracted during longer hours than strength admits.” Work must make way for the other tasks of the day.

Man must have time for prayer, for rest, for conversation with his family, for his hobbies, and for helping his neighbor. When work is over man must remain a man, that is to say, a social being.

Excessive work crowds out other obligations

How should work appear in relation to the tasks of human life as a whole?

Even when human strength is husbanded, it wears out irreparably. The night’s rest does, indeed, renew our strength. Sunday invigorates us for the coming week.

But there comes a time when a night, a weekend, a holiday, or a stay in a health resort cannot help any more. “For all our days are spent; and in Thy wrath we have fainted away. . . . The years of our life are threescore and ten years, or even by reason of strength fourscore; yet their span is but toil and trouble” (Ps. 89:9-10). Age, sickness, unfortunate events in our life and in work itself: all these things take their toll.

God gave man strength for the performance of life’s tasks in their entirety. To arrive at perfection, a long span of life is usually necessary. This is why, with certain exceptions, human life lasts a long time.

Work should not burn up human life too early, for man would then not be able to fulfill all the tasks of his life. People are inclined to neglect their duties to God and their souls; it is the interior life that is most threatened by excess of work.

Moreover, the skill that man acquires in work only comes with the years. A young man just beginning work usually spoils his material at first. It is only when he is older that he attains a certain amount of experience, which raises both the value of the man and of his work. The experienced worker is usually elderly. It is necessary, therefore, to wait for ripeness of years.

Work that is too exhausting physically makes it impossible for us to acquire moral virtues and perfections. This catchphrase, “the greatest possible output of work,” has shown that man, working in accordance with this motto, will be a good worker for a certain while but will then become incapable of any of the other tasks of life. Social workers have arrived at the conclusion that overworked people are not fit for social activity. Nor are they capable of developing within themselves many of the human virtues.

It sometimes happens that the more that physical strength is used, the more feebly life develops in other ways and the less progress is made in spiritual work. From this originates the one-sidedness of a certain human type, which may be noticed especially in proletarian or peasant environments.

Such a man can ask, “For what profit shall a man have of all his labor and vexation of spirit, with which he hath been tormented under the sun?” (Eccles. 2:22).

It is very easy for overworked people to become materialists. Poets can write so beautifully of times of work in nature’s bosom, while the actual workers do not even see the nature that surrounds them. They do not have time to wonder at its beauty. They do not see the charm of the mountains, the sunset, or the miracles of vegetation. Sometimes mountain dwellers are shocked when they hear townsfolk admiring these “rocks.” Theirs is usually a utilitarian and material attitude to nature, and this is the result of too one-sided, too heavy work. It is necessary therefore to conserve man’s strength for life’s tasks as a whole.

Once upon a time there were longer rests in work. The Angelus set a limit to evening work. No one dared work longer in the field. In the same way in the Old Testament they only worked until sunset. On the vigils of feasts, devotions ended the working day — this was the old “English Sabbath.”

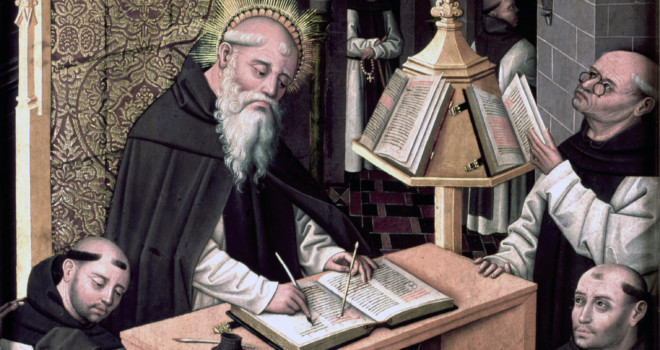

Artisans, apprentices, and masters all used to come to these devotions, for this was their service. There were also longer holidays in connection with periodic feasts such as Easter and Pentecost. These workers’ holidays, which are so extolled today, were for centuries supported by the Church by means of feasts lasting several days, which took one away from the burden of work. Here and there artisans kept the custom of stopping their work from Easter Sunday until the following Sunday.

Today the feasts and the customs connected with them are disappearing. But it is necessary to defend them, for they are the deliverance of human life.

Concentration and our inner attitude

But what is one to do when there is too much work? How does one increase time, when God made the day too short and the night too long? This is the problem to be solved.

Its solution lies rather in man’s inner attitude. On him depends the place that the time for work takes in the scheme of things. It is a question of the formation of our inner psychological attitude to work. We must say to ourselves, “Do what you are doing.” It is necessary to avoid scattering or overlapping our activities; our deeds must be “full before God” (cf. Rev. 3:2). This is the command that calls for concentration in work.

Work is often inefficient because we do not possess the art of concentrating on our work; we lack order in our thoughts and in our performance. We must therefore intensify our inner efficiency. Much evil and waste of time flow from inner disorder. That is why we are commanded to avoid inner division and the dispersal of our thoughts. The problem of “lack of time” is not to be solved by haste, but by calm. We must acquire calmness in work. Diffuse haste only increases work. We must begin by putting in order our inner spiritual attitude.

But organization on the material side (that is, our method of planning work to increase our amount of time) is also important. This is where the directors of work come into their own.

This is the background against which we arrive at a better understanding of God’s commandment: “Six days shalt thou labor, and shalt do all thy works. But the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord.”

Editor’s note: This article is adapted from a chapter in Sanctify Your Daily Life, which is available from Sophia Institute Press.