For an entire millennium, Christendom has lived under the assault of Islam. From the 7th-century Arab conquest of what until then had been the heartlands of Christianity (Israel, Syria, and North Africa) to the last Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1683, Christian communities had to face the determination of Muslim caliphates and kingdoms to follow Islamic law and wage jihad against the infidels. This evident, undeniable fact is incredibly absent from our historical conscience, as well as from evaluations of the intellectual and artistic achievements of our civilization under such unhappy conditions.

The Islamic threat was not always the same, but it regularly resurfaced. The Crusades, when observed from this broader perspective, were merely a brief parenthesis, an isolated counterattack that followed an important Islamic victory (in Anatolia) and embodied the new principles of a bold papacy that after the Gregorian Reforms saw itself as the true leader of Christendom.

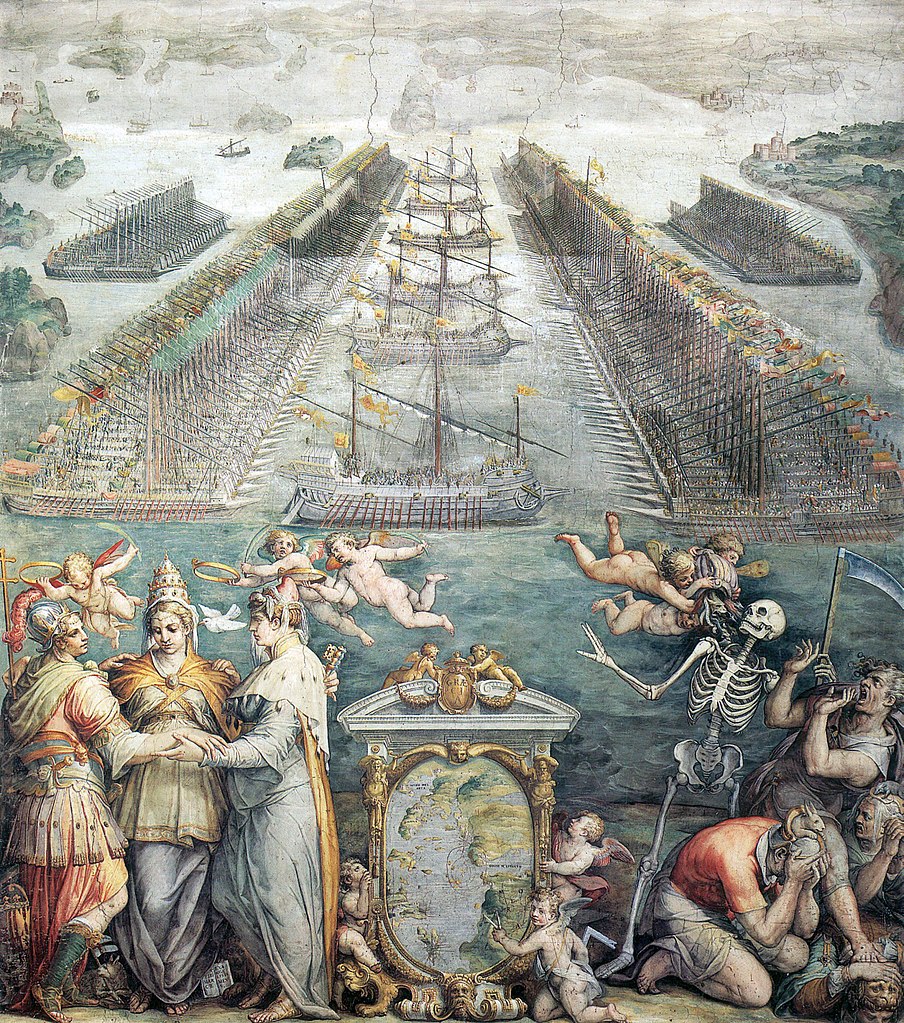

Prelude to Battle

This premise is important when approaching the Battle of Lepanto. What happened in the bloody confrontation lasting for many hours on October 7, 1571, in the waters of the Ionian Sea near the port of Nafpaktos, was part of the war of Cyprus. This conflict, in turn, was part of a longer phase in the confrontation between the Ottoman Empire and the Catholic coalition, led by the Habsburg monarchs. This phase had began in the aftermath of the 1453 fall of Constantinople, when under the direction of sultans Mehmed the Conqueror and Bayezid II the Ottomans had for the first time built an enormous fleet, able to carry out already in 1480 a surprise attack on Otranto, in Southern Italy, where women and children had been taken as slaves and the entire male population massacred.

In 1499, this fleet defeated, for the first time, the Venetian galleys, signaling the rise of Ottoman power in Eastern Mediterranean waters. In the meantime, other Islamic naval forces based in North Africa—encouraged and strengthened by Muslim exiles leaving Spain after the Reconquista—had revamped the Islamic tradition of intensive raids in the Western Mediterranean. Robert Davis has estimated that between 1530 and 1800, over a million European Christians were enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast.

If now we narrow our focus on the events closer to Lepanto, it is clear that by 1570 the Ottomans were succeeding in uniting the Islamic territories of the Mediterranean—an objective visible since at least 1517, when the Ottomans had overwhelmed the Muslim Mamluks and occupied Egypt. In line with this desire to lead the whole Islamic world, in 1534, the sultan had named the North African corsair Barbarossa grand admiral of his fleet. By the 1570s, Spain had lost virtually all its outposts in Barbary, without which effective defense of the Western Mediterranean from corsair raids was impossible.

In the meantime, even Malta had been put under siege by the Ottoman fleet. And in the Eastern Mediterranean, Venice was increasingly under pressure. More importantly, the main fleet of the sultan had not suffered a defeat in a very long time, and this created a general feeling of doom and gloom among Christian captains and soldiers. Surely, part of the reason for the Ottoman success was the Protestant rebellion, which distracted Habsburg resources and energies from the Mediterranean front, and the longstanding defection of a major Catholic country, France, which since the 1520s had entertained friendly relations with Istanbul and even encouraged the Muslims to attack the Habsburg dominions in Eastern and Central Europe.

Pope Pius V, John of Austria, & the Holy League

Yet Pope Pius V, in Rome, was surely not among those who could easily be discouraged. And this elderly, frail yet stubborn saint would join forces with a very different man, the young, dashing and knightly John of Austria, illegitimate son of Charles V and half-brother on Philip II, king of Spain. Thanks to the patient, painstaking work of Pius V, a Holy League was formed that gathered almost all of Christendom. In the early days of September 1571, a fleet comprising among others Spanish troops and Genoese galleys, Papal ships and knights of Malta, Venetian galleasses and Tuscan reinforcements, met in the port of Messina, Sicily. Endless conversations and bitter disagreements ensued. The constant prompting of the Pope, who could not conceive of a good reason why the fleet would not move towards the enemy, and the impatience of John, who disregarded the cautious suggestions of Spanish officers, eventually convinced the captains to set sail towards the Ionian Sea, in search of the Ottoman navy.

John’s decisiveness was once again crucial during the evening of October 6, when he ordered to coast the Echinades islands and approach the Gulf of Patras notwithstanding an unfavorable breeze. On the morning of the 7th, the Ottoman fleet was sighted, and John disposed his vessels in a carefully arranged line of battle, with the Venetian galleasses at the front of the left wing, while the Genoese galleys of the Doria family took the right. The Spanish infantry, one of the best in the world, stayed put in the larger galleons, knowing that in a full-scale confrontation between the fleets, their moment would come.

During the hour before the first shots were fired, aboard the Christian ships thousands of soldiers and sailors received the Sacraments and fell to their knees, while Capuchin and Jesuit priests took turns to hear Confessions and lead different groups in prayer. Then, they gave the final absolution, while the enormous banner of the Holy League with the image of the Crucified Christ was lifted above the flagship. The wind changed, and the sun shone across the water that would soon turn red with blood. Under the cloudless sky and their purple banner with the name of Allah woven in golden letter, the Ottomans approached. They were commanded by Ali Pasha, admiral, and Uluç Ali, who was the son of a Southern Italian farmer, captured and enslaved by Berber pirates, then convert to Islam and himself a corsair.

The Beginning of Battle

The battle started with a promising move for the Ottomans, who first attempted to round the Holy League on their left. When Doria stretched his line of galleys to prevent this, he found himself so far to the right that a gap opened between the Genoese and the Spanish and Papal vessels. In fact, the Turks tried at that point to force Doria into the open sea, away from the fighting. However, on the left wing of the Christian line, the Venetians, led by Francesco Duodo, had superior artillery mounted on six galleasses of new construction. The Ottomans might have initially mistaken these larger warships for store ships accompanying the Christian fleet. Instead, as shown in a manuscript at the Archive of Simancas, John had listened to the suggestions of his Venetian allies and deployed these novel, larger and heavily armed galleasses right in front of the rest of the Christian line on the left wing.

When Duodo gave the order to open fire, he had at his disposal, not only officers from the Venetian nobility and sailors from Venice’s dominions, but also Antonio Surian Armeno, a fascinating figure, half scientist half craftsman, and Zaccaria Schiavina, head of the Venetian bombardieri. Armeno and Schiavina had probably employed their time in Messina very well, perfecting the training of more men in the use of artillery pieces aboard the new ships.

Even after the heavy Venetian bombardment utterly destroyed tens of Turkish galleys, the Ottomans were still able to approach the Venetian ships and begin a hand-to-hand fighting. Here the Italian crew would have been easily defeated by the Islamic janissaries, if not for the intervention of Christian slaves freed from some Turkish galley and promptly armed by the Venetians. The right wing of the Ottoman fleet was undone.

In the meantime, at the center of the battle, the two flagships had made contact, and the crews were engaged in a bloody battle fought over the docks. Spanish infantrymen led by John were nearly overwhelmed by the Turkish janissaries, but at the crucial moment neither side could get reinforcements from the southern end of the battle (the right end of the Christian line), while John received the decisive help of Marcantonio Colonna, the Roman aristocrat in charge of the papal flagship, covered by the Venetians’s success on the left. In the last phases of the battle, the great Ottoman admiral Ali was killed, and the banner of his flagship was taken. Skirmishes continued, but most of the other Ottoman galleys retreated, while the Christians pursued only halfheartedly due to a change for the worse in the weather.

The Rosary & Fasting for Battle

It may sound odd to modern ears, but one of the decisive factors in the outcome of the battle was the spiritual leadership of Pius V in Rome. According to Ludwig von Pastor, in the days preceding and following this historic Christian victory, Pius V had led the people of Rome in fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. On August 27, Pius had asked all his Cardinals to fast for at least one day a week and to give to the poor from their own property. A month later, on September 27, the Spanish ambassador in Rome witnessed that the Pope was fasting three days a week, and even while physically weak, he was praying unceasingly.

A form of prayer that Pius especially encouraged was the Rosary, as he firmly believed in the graces that come to us from God through the Blessed Virgin Mary. When he was woken up in the middle of the night on October 21 and first heard the news of the battle, Pius uttered the words of old Simeon in the Gospel of Luke: nunc dimittis servum tuum in pace. In the following days, he celebrated solemn Masses and invited his flock to give alms for the celebration of more Masses, to the benefit of the men who had died, rather than wasting the money in secular celebrations and parties. Then, realising that the victory had taken place on the same week when the confraternities of the Rosaries traditionally went in procession across the city, Pius instituted a feast for “Our Lady of Victory”—later changed by his successor Pope Gregory XIII into the “Feast of the Holy Rosary.”

Our Lady of Victory at Lepanto

The military success at Lepanto was of a defensive nature. The Holy League prevented a further expansion of Ottoman power across the Mediterranean, but it was not able to capitalize on its victory to question the territorial gains of the Turks or even simply to limit the power and reach of Islamic corsairs. It took only three years for the sultan to rebuild a fleet of the same size of the one he lost in the waters off the Greek coast in October 1571. And as late as 1696, the papal legate Cardinal Corsi was surrounded in Rimini by “a mob of poor women, whose husbands were slaves” taken by the Turks. Lepanto was therefore not so much a turning point in the military history of the Mediterranean. It did not interrupt the millennium of Islamic assault against Christendom that I sketched at the opening of this brief article. Yet, Lepanto marked an important psychological change, as it proved that the Islamic power at sea could be challenged and that the main fleet of the Ottoman sultan was not invincible.

Furthermore, Lepanto confirmed that the Church emerging from the Counter-Reformation had revived its spiritual leadership of the Christian peoples. This was true not only when one looks at the moving example and tireless action of a saintly Pope like Pius V, but also when considering the help provided by the Queen of Heaven, whose role in salvation history and in the spiritual economy of the world had recently been denied by the Protestant ‘reformers.’

✠

image: Painting of Battle of Lepanto in the church Iglesia de Santa Maria Magdalena by Lucas Valdez (1661 – 1725), photo by Renata Sedmakova / Shutterstock.com