Starting December 1, the nine justices of the Supreme Court will begin work in earnest on what already looks to be the court’s most closely watched—and probably most controversial—ruling in nearly half a century.

When the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is handed down, probably next spring or early summer, it will do one of three things: either overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that legalized abortion, together with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 decision affirming the central holding of Roe; or else permit individual states to impose meaningful restrictions on abortion, though without reversing Roe and Casey entirely; or else, heaven forbid, deliver a bitter setback to the prolife movement by permitting death-dealing Roe/Casey regime of abortion on demand to remain in place.

December 1 is the date set by the court for oral arguments in Dobbs. The case comes from Mississippi and concerns a law enacted in 2018 that bars abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy except in cases of medical emergency or severe fetal abnormality. Lower courts have ruled against this law as a violation of Roe.

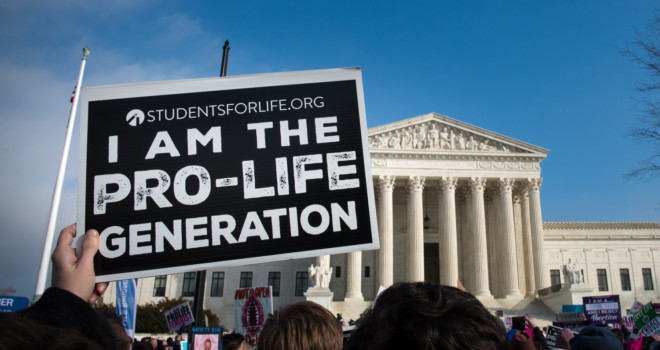

The intense interest in the new case has already generated a virtual tsunami of pre-argument commentary. Much of it, coming from the pro-abortion side, has adopted a remarkably vituperative tone and apparently been designed to intimidate prolife members of the Supreme Court. Further heightening the tension was the hubbub accompanying the Texas “heartbeat” law argued before the court on November 1. The Texas law bans abortions after the point at which a fetal heartbeat becomes detectible—usually, the fifth week of pregnancy.

Up to now, the Supreme Court has been asked to consider only procedural issues concerning the Texas law rather than the central question: Is it constitutional? Some abortion providers are seeking the court’s green light to bring suit against the law even before it is enforced against them. And the Justice Department, taking its cue from President Biden’s declaration that the law is an “unprecedented assault” on the right to kill the unborn, wants authorization to sue the state.

Whatever the Supreme Court does about these matters, lower court battles over the Texas law’s constitutionality come next. Besides Texas, several other states are already in line—and more are on the way—asking the Supreme Court to say yea or nay to their laws restricting abortion. But Dobbs will be first, and the Supreme Court most likely will keep Texas and the others waiting until it has established new legal ground rules in deciding that case.

Guessing how individual justices will vote is risky. But with that qualifier, a pattern seems clear enough. Three—Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—are certain pro-abortion votes. Three others are good bets to favor overturning Roe/Casey—Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch.

That leaves three—Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. All are pro-life, but one or more of them might favor some modification of Roe over outright reversal. Give it six months or so, and we’ll find out.

Meantime a line from an amicus curiae brief—one of many submitted in the Dobbs case—sticks in memory. Recognizing the personhood of the unborn, say legal scholars John Finnis of Oxford and Notre Dame and Robert George of Princeton, would not require “unusual judicial remedies” but would simply “restore protections deeply planted in law until their uprooting in Roe.”

Are you listening, Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett?

✠