Something is different about the Gospel of John.

Something is different about the Gospel of John.

The other three gospels — Matthew, Mark, and Luke — read like very much like historical narratives. Because of their similarity in structure and content scholars group them together as the Synoptics. John doesn’t follow their outline and his style differs in being deeply poetic, contemplative, and mystical. (For more on the contemplative aspect, see St. Augustine.)

The Gospel of John may be the fourth book in our New Testament, but many scholars actually date it to the end of the first century, potentially even later than the Book of Revelation. (See, for example, this timeline.)

The late date of the gospel puts its image of Jesus in context. It means that the Jesus of John is one of the last views of our Savior — if not the final one — that is presented to us in New Testament. It is the understanding of Jesus that is built upon the foundation of the other three gospels, Acts, all the epistles of Paul, and, potentially, even Revelation. In a way, it represents the final reflection of the first Christians on the reality of Jesus Christ.

And, what we see as we move further from the time of the events described is that Jesus is presented in more universal terms. Consider then opening lines of the first three gospels:

Matthew: The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.

Mark: The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ

Luke: In the days of Herod, King of Judea, there was a priest named Zechariah (This is verse 5, which is the real beginning after a preface on method.)

Contrast how John begins:

In the beginning was the Word.

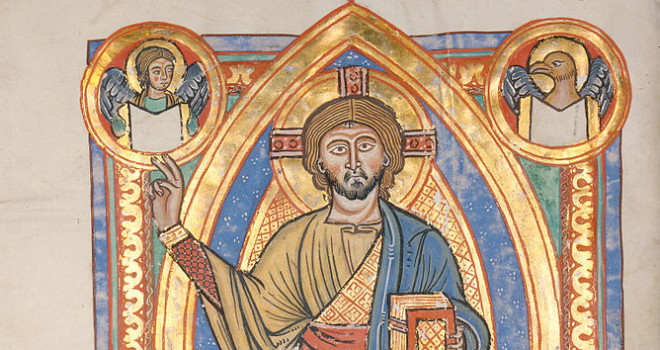

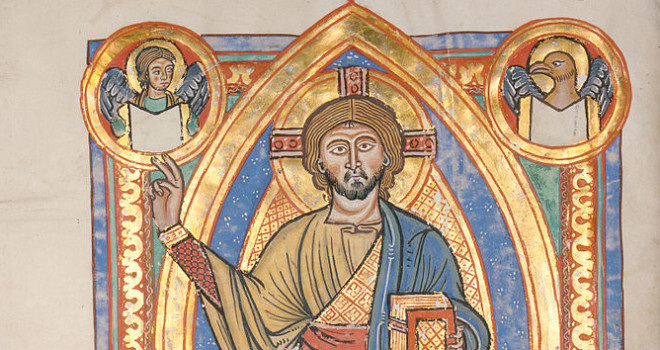

The first three gospels are firmly grounded in the historical Jesus. John is too, of course, but his initial perspective is a cosmic one. He looks back to the Jesus present at the beginning of time. The first verses of the Gospel of John are heavy with universal concepts—creation, nothingness, life, light, the human race, darkness, the world, flesh, glory, grace, and truth. Behind them stands eternal being itself: the Word who is with God and is God.

Some might say that the divinity of Jesus is emphasized more in the Gospel of John than the other three gospels. But the Jesus of John is, in some ways, humanized even more. Jesus weeps (John 11:35). He tires and asks for a drink from the well (John 4:6-7). On the cross, He thirsts (John 19:28).

The Bread of Life discourse in John 6 has one of the grittiest descriptions of the reality of the Eucharist anywhere in the Bible. Only John has the story of the piercing of the side and the fountains of blood and water that came out. And again, only John has the story of Thomas assuaging his doubts by sticking his fingers in His side. In short, the Jesus of John is presented in his raw humanity.

This emphasis on humanity is reflected in what Pope Benedict XVI identifies as some of the dominant images of John: water, wine and vine, bread, and the shepherd (source: Jesus of Nazareth).

Jesus in the fullness of His humanity and His divinity perhaps comes together most acutely in the famous ‘I am’ statements of the gospel:

- I am the bread of life; 6:35, 48, 51.

- I am the light of the world; 8:12; 9:5.

- I am the door of the sheep; 10:7, 9.

- I am the good shepherd; 10:11, 14.

- I am the resurrection and the life; 11:25.

- I am the way, the truth, and the life; 14:6.

- I am the true vine; 15:1.

(Source here.)

The first part of these statements — the ‘I am’ — identifies Jesus as God in the terms He used to introduce Himself to Moses in Exodus 3:14, ‘I am Who I am.’ In the second half of these statements we are presented with terms that have both earthly and heavenly meanings — bread, light, door, life, and true vine, to name a few.

This is a kind of universality to these things. Nearly every fundamental human need is either stated or represented here: food, light, a sense of belonging, eternity, the good life, truth, and joy. The message seems to be that only the universal God Who—the ‘I am’—could be a provider of the universal needs of mankind. As Jesus Himself says early in the gospel, “What are you looking for?” (John 1:38; see also my previous article on this).

In other words, the further in time the early Christians were from Jesus the more radiant the truth of the Incarnation. Much like the rays of the sun over the distant earth, so also, with the perspective of time, the light of Jesus clearly shone over all things.

The Jesus of John is both cosmic and concrete. He is the Word through which all creation came into being and the One Who was wounded for our sakes. He is being and bread, wisdom and way, invisibility and light.

The Jesus of John thus becomes an invitation to a personal encounter with the person of Jesus. He is the only person who can satisfy every longing and deepest desire — not simply because He carries within His being the cosmos but because He is the cause of it coming into being. Whatever you seek — whether eternal wisdom or a few crumbs of bread and a sip of water—you will find it in Jesus.