It is striking, when reading about the saints in their own words, just how terrible an opinion they hold of themselves. But it makes sense: as sanctity grows, so too does the awareness of one’s own sinfulness.

St. Gemma Galgani was a mystic visionary who died at the age of 25 in 1903. Her intimate mystical union with Jesus afforded her a clear-sightedness and acute perception of how sin pains Jesus, and convicted her to root out her imperfections at any cost. She was unflinching in accusing herself of sin, and deeply remorseful for even the smallest offense against God. Gemma’s diary can have the same effect on the reader.

As seen in the lives of many saints, Gemma was assailed by demonic attacks during her short life that escalated to physical assaults. But she always cites temptation to sin as the greatest and most painful of these attacks.

As the catechism tells us, the demons’ main goal is to tempt us to mortal sin. If they can get us to employ our own will and thereby kill our own souls, they do not have to resort to more extraordinary forms of attack. Mortal sin is the surefire path to hell, and so they will gleefully achieve their goal by this path of least resistance whenever possible.

Gemma was often tempted to all manner of sins, but she self-diagnosed her predominant fault as vanity. As recounted in her diary, Gemma struggled with a temptation toward worldliness. This may seem surprising given her secluded state in life, the fact that she was sickly and often bedridden, her virtue, her continual conversation with the Church Triumphant, and her total devotion to Jesus. Nonetheless, the first time her guardian angel appeared to her, it was to rebuke her for worldly vanity. Gemma had been wearing a new gold chain in town, eager to show it off to her peers. Her guardian angel said to her: “Remember that the precious jewelry that adorns a spouse of the crucified King can only be thorns and the cross.” From that moment on, Gemma removed the chain and a ring that she was wearing, and resolved to live for Jesus alone, and to “not even speak of things that savor vanity.”

Wearing jewelry is not a sin in and of itself. But in Gemma’s case, it acted as an obstacle to the heights of sanctity to which she was called, and thus had to be ruthlessly removed despite the temporal joys it brought.

Another such instance was Gemma’s participation in a worldly conversation between her sister and her friends. Even though Gemma says that the conversation was not sinful (it did not include gossip or slander or impropriety), her guardian angel admonished her for focusing energy on such worldly subjects.

Indulging in the things of the world can have detrimental effects on our souls because we slowly lose sight of heavenly things and begin to develop attachments to the world, which can lead us to sin bit by bit. It’s harder to resist sin when sinning would allow us to keep our worldly attachments. Or when sin becomes the only course that will allow us to keep these attachments. We love what we value and what we give time to. If so much time and energy and gift of self is given to worldly things, that becomes our identity.

Even unequivocally good things became temptations to worldliness for Gemma because they distracted from her primary call to serve God in prayer and suffering for souls.

One striking example illustrates how God directed her away from something that was good in favor of a greater good.

When her health allowed, Gemma habitually took walks to give alms to the poor, greeting people along the way and developing friendships. This is an obviously good act, an example of a generous and unselfish corporal work of mercy. However, her spiritual director forbid her from continuing, determining that these walks were serving as a tie to the world and occasion of vanity for Gemma.

Gemma writes: “In this way, Jesus worked in me a new conversion. The result is that I grew tired of clothes and everything else.”

The worldliness that was a byproduct of these walks would have hindered Gemma’s spiritual growth, even if this was not evident at the time.

Unique, Unconventional Vocation

Throughout her life, Gemma had a strong call to become a Passionist nun. She attended class and made retreats with the local Passionist convent. But due to her poor health, her application to the convent was declined. But Jesus had greater plans for her: mystic visions, her role as a victim soul, and the gift of the stigmata. Gemma is considered to be mystically espoused to Christ, albeit without vocational vows.

St. (then Venerable) Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, himself a Passionist monk who died in 1862, regularly appeared to Gemma to console and direct her. Jesus and Our Lady personally gave Gemma the task of suffering for the soul of Mother Maria Teresa, former prioress of the local Passionists. When Mother Maria Teresa ascended from Purgatory to Heaven, she appeared to Gemma in glory to thank her. Additionally, Gemma displayed great obedience to her spiritual director (who ordered her to write her diary) and to Jesus, Our Lady, and her guardian angel’s directives. Gemma thereby lived out her Passionist vocation outside the convent walls. It wasn’t the life she had wanted, but it was the life God wanted for her.

Specifically because her temptation to vanity and worldliness was so strong and difficult to resist while living at home, Gemma yearned even more for the convent. She wrote after a retreat: “The thing that afflicted me was the thought that I had to return to the world. I would have preferred to remain there (even though that form of life did not appeal to me) than return again to those places where there were many occasions of offending Jesus.”

Gemma could not have used religious life as a way to escape temptation, because the devil adjusts his temptations and increase their intensity to match one’s state in life. God willed that Gemma fight these temptations in the world. She faced many challenges in this setting: boredom, loneliness, dryness in prayer, rumination and scrupulosity, and hostility of family members. Most notably, her younger sister Angelina constantly mocked and harassed Gemma for her sanctity, sometimes preventing Gemma from the deep prayer necessary to go into ecstasy. It was also harder for Gemma to attend daily Mass as frequently as she would have as a nun. Without the regimented structure of the convent, the obstacles to Gemma’s prayer life were increased – she had to prove her dedication to Jesus in these more challenging circumstances.

Gemma is a heroic example to all who live in the world but strive to never be of it. She shows, to a precise degree, the dangers of worldliness and that no sacrifice is too much for union with Christ.

✠

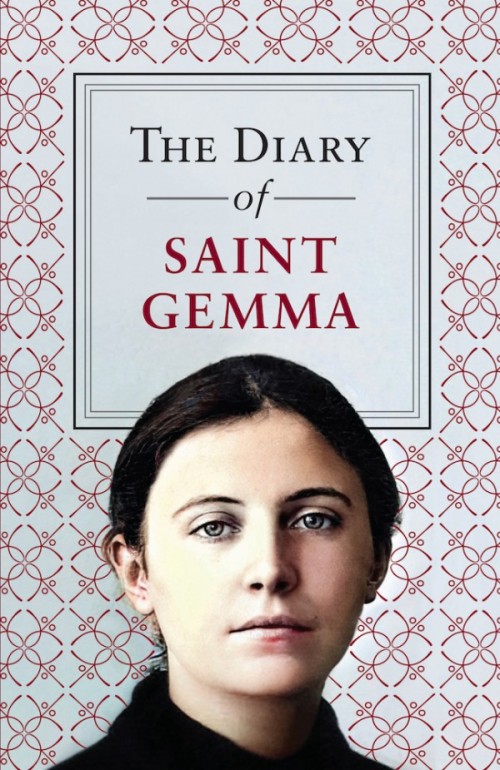

The Diary of Saint Gemma is available now from Sophia Institute Press.