“Slave of the slaves, forever.” This is how St. Peter Claver, apostle to the slaves of Cartagena, signed his name upon his ordination. His life was an embodiment of Matthew 25:30, in which he proved that ministering to “the least of these” is not only a moral imperative, but a hidden treasure of graces for those with eyes to see.

Paradoxical Freedom

Peter Claver was born in Spain in 1581 to a pious family. He joined the Jesuit order and was sent as a missionary to Cartagena, now present day Colombia, but then, hub of the equatorial slave trade.

As Arnold Lunn writes in his incisive biography of Claver, “This simpleminded saint held with passionate conviction the belief that it was better to die a Christian slave at Cartagena than a native chieftain in the Congo. The slave trade was full of perils for the slave trader, but on the balance, a boon for the slave. Grotesque as though this conclusion must seem, the intelligent humanist must concede that it is a logical conclusion from the Catholic premise.”

Claver saw the great spiritual opportunity in ministering to those to whom suffering in this life was inevitable. He encouraged the enslaved, with eyes on Heaven, to see that the chains in this life only served to further renounce the corruption and vanity of this world. While advocates of emancipation focused their efforts on slavery, Claver was devoted solely to the slave. While others rightly condemned the institution, he concerned himself only with souls.

Claver saw in the person of the slave not an abstraction, but the paradox of the Christian life – the very paradox of the cross. He taught the enslaved that by embracing suffering under injustice, they were in a unique position to open themselves to a multitude of graces. Yet at the same time, he restored their humanity by reminding them of their true dignity as children of God.

There is no conversion more urgent than that of someone on the point of death, and Claver’s first line of defense was to baptize the dying on the decks of slave ships. But moreover, he taught the enslaved to live out the rest of their lives as Catholics, even in their tenuous circumstances. He prioritized worthy reception of the sacraments and robust moral development. Claver even made a point to undergo mission trips to continue to minister to slaves who had been sold to other locations, often traveling days through swamps and mountain ranges.

Claver’s otherworldly clarity of sight astonished fellow Spaniards and gained the love of his enslaved catechumens. When this world is shorn of its vain trappings, superficial promises and ephemeral beauty, one cannot but focus on the eternal, unchanging promises of the next life.

The bondage of aristocracy

As a central port to the Americas, Cartagena was frequently flooded with a multitude of diverse voyagers from all global empires of the era. While Claver had a special devotion to the enslaved, he possessed the ability to communicate the Gospel across a multiplicity of audiences, and made converts from all walks of life. He could minister equally to European prisoners of war, leper colonies, and exiled criminals. He is even believed to have gained some conversions among Muslim prisoners of war.

The life and times of Peter Claver highlight another, similar paradox: the ironic slavery of the privileged. Our Lord Himself warned about the risks inherent to souls bound by the vanities of riches and status. We see an incarnate example of Our Lord’s warning in the person of the Anglican archdeacon of London, whose imprisonment at Cartagena ironically may have saved his soul.

Six hundred English prisoners of war had been taken after a territorial skirmish with Spain for the islands of St. Christopher and St. Catherine. Among these were many high-status officers, including the Anglican archdeacon. Claver intuited that the man was uncomfortable in his heresy and schism. The archdeacon admitted that the only reason he remained in the Church of England was to secure a future of status, privilege, and wealth for his family. Vanity of vanities! He implored Fr. Claver to pray for him, and demonstrated his intent to die a Catholic. A week later, Claver found the archdeacon dying at the hospital of St. Sebastian, and there secured his conversion to Catholicism.

The Anglican archdeacon represents, in many ways, the foil to the slave: he possessed position, acclaim, riches, family, education. But who of these would Peter Claver say was truly free? These very blessings served to enslave the archdeacon to sin until in the final moment he cast them off.

The paradox of bondage manifested itself again in Claver’s conversion of a prisoner condemned to death. After his meeting with Claver, repentance, and reception of the sacraments, he was able to rightly and accurately inscribe in his prayer book “This book belongs to the happiest man in the world.”

The world views sickness, death, slavery as prisons – Claver saw them as instruments of liberation from sin.

To quote Lunn, who, inspired by the saints had himself walked the path of conversion: “There is surely something to be said for a religion that teaches men not only to relieve the sufferings of others but also to accept with courage and – supreme paradox – with gratitude the inescapable sufferings that come their way.”

The many conversions of St. Peter Claver illustrate that true freedom comes only through complete surrender to Christ, and is a prize worth any cost in this world.

✠

Editor’s note: The biography of St. Peter Claver, A Saint in the Slave Trade, is available as an ebook or paperback from Sophia Institute Press or your favorite bookseller.

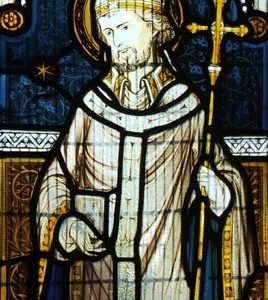

image: St Peter Claver on stained glass, St Aloysius church in Glasgow / Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. / Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)