“She pondered all of these things in her heart…”

I’d hear this beautiful description of Mary’s love and instantly grow sad. It wasn’t that I didn’t ache for the ability to carry hidden truths, even difficult ones, in my own heart – with love, it was that I didn’t know how to. My own brokenness kept my heart in a state of fragility and defensiveness.

Growing up in a devout Catholic family, one would believe that I knew what it meant to embrace Mary’s love. I didn’t. We faithfully attended Mass every Sunday and Holy Day of Obligation, pray before meals, and my parents would bless my younger brother and me every night before bed. I owned a rosary but seldom prayed it.

Mary was a distant heroine to me, a woman whose mystery baffled me. How could a woman quietly keep so much in her heart? And why? I couldn’t relate to that with my own exuberant, passionate temperament, especially with frequent outbursts of opinion and frustration that often left my parents holding their heads in their hands.

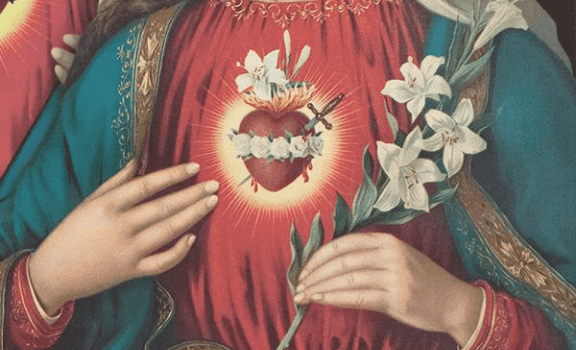

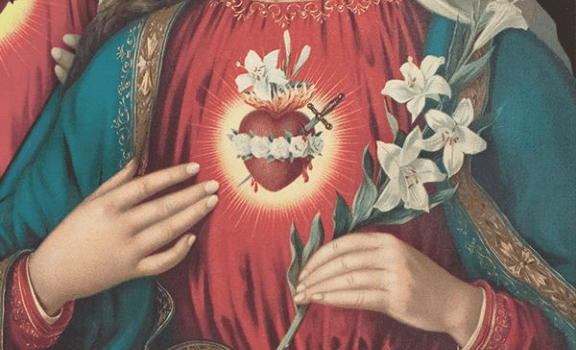

Still, I’d cradle the shiny, laminated holy card with the image of the Immaculate Conception and beg her, “Mary, please help me be more like you.” A relationship with her seemed impossible, because she was perfect, and I knew I was not.

After I became a mom in my early thirties, I revisited my concept of dialoguing with Mary. That first Advent, I never followed a daily devotional or lit a candle on the wreath. It seemed like utter failure to neglect such rituals. But my mom said to me something I would never forget: “You are living your Advent.”

I internalized this message every liturgical season thereafter: Christmas, Lent, Easter. Gradually, I’d turn to Mary and ask her to teach me what it meant to be a mom, because everything about motherhood intimidated me. I realized I knew very little about nurturing tiny infants, and it frightened me.

The prayer of St. Teresa of Calcutta often carried me through the chronic sleep deprivation and dark moments of doubt: “Mary, please be a mother to me now.”

Over the years, I learned what it meant to “ponder all these things.” It meant to hold space for the Holy Spirit at all times, to be tuned in to His quiet whispers and movements, to be aware of when He was speaking to me or resting with me or asking me to wait on His timing.

As I pondered, I felt Mary’s presence more strongly, as if she were guiding me to a deeper love for God. Then it occurred to me: hers was both a receptive action and an active receptivity. Because Mary embodied the fullness of every virtue, pondering was both a vigilant activity, as well as a passive receiving. Both are necessary in relationship with God.

In the concept of active receptivity, I am reminded of the parable of the ten virgins. Half are wise, half foolish. The wise virgins stay awake for as long as it takes for their Bridegroom to return to them, ensuring that their oil lamps do not run dry. The foolish ones long for Him, too, but they fall asleep, because they cannot stay awake for the allotted time.

Vigilance is crucial in spiritual growth. Most of what happens to us is beyond our control. In fact, we spend lengthy amounts of time just waiting. Sometimes we wait for an answer to prayer. Mostly, we wonder why we are waiting, or for Whom. We are told that Jesus is coming someday, and no one knows the hour. But it’s easy to become complacent, falling into the trap of acedia, and simply presuming it’ll never be in our lifetime.

Staying awake means leaning our hearts, alongside Mary’s, into the Heart of God. It involves an astute awareness of who we are, what we are capable of (both good and evil), and relying entirely on God in daily surrender of what we do not understand or cannot change.

Receptive action involves listening. A heart like Mary’s is a heart that listens. It is one that notices things, small things, like the facial expression of one person in a crowd that speaks of sadness or loneliness. When our hearts are open, we find that the subtleties in our surroundings and conversations become grand gestures or invitations for healing and encouragement. Somehow, receptivity expands our capacity to love.

I see this now that I am a mother of five young children. And I continue to rely upon Mary as my Mother, but my confidence in her extends to the love and maternal care I know she offers my children, especially when I cannot be with them to protect or nurture them.

Learning to love is the greatest gift of motherhood, one that cannot be replicated in any other vocation quite in the same way. And when I liken my heart to the heart of Mary’s, I find that I am able to give until it hurts, to be emptied until God is ready to fill me again.

✠