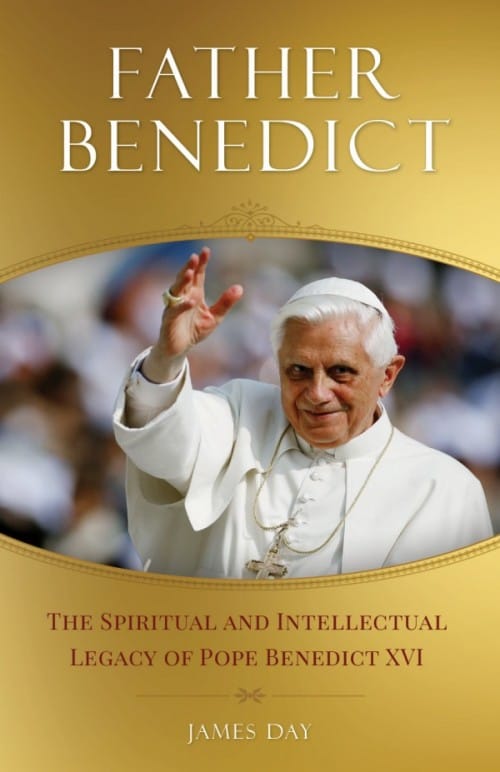

Editor’s note: In commemoration of the recent death of Pope Benedict XVI, Catholic Exchange is issuing a series of reflections on some of his most monumental encyclicals, excerpted from James Day’s 2016 book Father Benedict:The Spiritual and Intellectual Legacy of Pope Benedict XVI.

In meeting with United States bishops during his voyage to America in April 2008, Pope Benedict was asked to reflect on “a certain quiet attrition” that is seeing a pervading loss of faith sweeping the globe and various definitions of what “being Catholic” means today. Churches are closing, vocations are fading, religious orders

are vanishing, and, to many, quaint Catholic customs and teachings are struggling against the authorities of science, reason, and personal autonomy. In terms of sheer numbers the New Evangelization seems destined not to have the effect Benedict had hoped.

Such a situation was envisioned as early as 1970 by Joseph Ratzinger: “The reduction in the number of faithful will lead to [the Church] losing an important part of its social privileges. It will become small and will have to start pretty much all over again.” Joseph Ratzinger saw the crisis coming, and as Pope Benedict he had a thorough grasp of what is leading to the abandonment of our Catholic Faith.

But he would not abandon the people entrusted to his care. When he set out to write his encyclicals, Benedict saw a world yearning for authentic freedom, justice, and happiness, but it was failing to achieve these things by human hands alone. With his two completed letters on the theological virtues, Deus Caritas Est, on love, and Spe Salvi, on hope, the Pope gives us a vision of a more authentic world and presents signposts of truth that have the capacity to reshape mankind’s trajectory in this very day and time.

“I wish in my first encyclical to speak of the love which God lavishes upon us,” Benedict XVI stated in the introduction to Deus Caritas Est (God Is Love), “and which we in turn must share with others.” It was not the type of inaugural encyclical that was expected from the newly elected pope who just spent nearly a quarter of a century as the cardinal prefect for the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith. Pope Benedict’s decision to release Deus Caritas Est indicated a sublime message: this will not be a sweeping papacy of ambitious theological pursuits geared to showcase Joseph Ratzinger’s intellectual command, but rather a return to the basics, to rebuild the fundamentals so that the Christian culture may be renewed and healed in its vocation to love and able to become again a beacon of hope in a world of darkness.

Deus Caritas Est addressed how love is perceived today, seeking to restore the timelessness and boundless understanding of love—the love of God, of Jesus Christ, and His Church. As the world struggles with the pain of divorce, chooses adolescence in lieu of adulthood, and believes the lies propagated by the hookup culture and pornography, Benedict shows us that the alternative—Christianity—has been neither properly communicated nor properly understood: “Doesn’t the Church, with all her commandments and prohibitions, turn to bitterness the most

precious thing in life? Doesn’t she blow the whistle just when the joy which is the Creator’s gift offers us a happiness which is itself a certain foretaste of the Divine?”

At the same time, Benedict is no less honest about the relativism that prevents an understanding of love: “For having reduced eros to pure ‘sex,’ it becomes a commodity, ‘a thing’ to be bought and sold, or rather,

man himself becomes a commodity.” Seeking inspiration to reintroduce love to a public growing

ever more cynical, Pope Benedict looked to the height of Christian poetry—Dante Alighieri’s La Divina Comedia. Recognizing that “today, the word ‘love’ is so spoiled, worn out and abused that one almost fears to pronounce it,” the Pope “wanted to try to express for our time and our existence some of what Dante boldly summed up in his vision.” In canto 33 of Paradiso, Dante describes the celestial light of a Trinitarian circle in which appeared “a human face—the face of Jesus Christ. God, infinite light, has a human face and—we may add—a human heart.”

Dante marvels in that canto, “Whoever sees that Light is soon made such that it would be impossible for him to set that Light aside for other sight; because the good, the object of the will, is fully gathered in that Light.” This is the “Light from Light,” the incarnate Love “born of the Father before all ages,” now entering our midst. “In this Encyclical, the themes ‘God’, ‘Christ’ and ‘Love’ are fused together as the central guide of Christian faith,”

Benedict describes.

The witness to the love of God as revealed in Christ lay at the heart of Benedict’s intentions in Deus Caritas Est.

Benedict begins his encyclical by revealing that Saint John’s statement of faith, “God is love” (1 John 4:8), not only was fulfilled in the person of Jesus Christ, but is Jesus Christ. In Deus Caritas Est and elsewhere in Ratzinger’s canon, we glimpse the remarkable love story between God and man. It was out of unconditional love that God became fully human and lived among us. He had to show us how to love, even if it meant death. Indeed, it did mean death (cf. Gal. 4:4–5). Benedict explains that the Crucifixion was not just the matter in which He died; it was

“love in its most radical form,” unconditional love itself.

For us, showing this same unconditional love to God and neighbor is possible because God made us: “Love is possible, and we are able to practice it because we are created in the image of God.”

Image by Frippitaun on Shutterstock