Much of the confusion concerning the virtue of mercy lies in the fact that it is not an independent virtue such as courage, kindness, gratitude, or generosity. Mercy does not stand alone. It is a complementary virtue and its necessary partner is justice. Mercy completes justice, as a tasty dessert completes a fine meal.

This unusual feature of mercy is well recognized in literature and in philosophy. Shakespeare tells us in “The Merchant of Venice” that mercy “seasons” justice. For Milton, in “Paradise Lost,” mercy “tempers” justice. According to Sr. Thomas Aquinas, “Mercy without justice is the mother of dissolution,” whereas “justice without mercy is cruelty”.

The 19th century American clergyman Edwin Hebbel Chaplin was most eloquent in his description of mercy when he said that “Mercy among the virtues is like the moon among the stars, – not so sparkling as many, but dispensing a calm radiance that hallows the whole. It is the bow that rests upon the bosom of the cloud when the storm is past. It is the light that hovers above the judgment seat”.

That mercy can crown justice is the subject of high drama. We find a stirring example of this in a play by Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811), “Prinz Friedrich von Homburg,” one that is not well known that is not widely known. In the play, the prince, son of the Elector of Brandenburg, disgraces himself in battle. He is subsequently tried by a court martial and condemned to die. The father wants mercy for his son in order to save his life, but cannot dispense this heartfelt virtue as long as the prince is unrepentant and rejects the canons of justice. Natalie, his love, intercedes in his behalf, but to no avail.

The Elector is unwavering; mercy cannot negate justice. As the play develops, the son acknowledges the gravity of his crime and the validity of his sentence: “. . . now that I have thought it over, I wish to die the death decreed for me! It is my absolute desire to glorify the sacred code of battle, broken by me before the entire army, with voluntary death”.

When the Elector hears these words, he is overjoyed. Now that the prince has accepted justice, he is eligible for mercy. The Elector tears up the death sentence, pardons his son, and grants him permission to marry Natalie. On this happy note, the play ends.

Despite the highly romantic quality of the play, its philosophy is nevertheless sound: mercy cannot be rightly dispensed without its intended beneficiary accepting and honoring justice. Kleist’s play is perfectly adaptable to a Christian way of thinking. Perhaps the most consoling words Christ ever spoke is what he said to the Good Thief: “Thou shall be with me this day in Paradise”. The thief was not “good” because he was a thief; he was good because he was penitent. He agreed that he was “justly condemned” (Luke 23, 39-43).

Mercy owes its virtuousness to its relationship with justice. When it is dispensed gratuitously it benefits no one, neither the giver nor the receiver. In that instance it is not, as Shakespeare said, “twice blessed”.

It is easy to love mercy, more difficult to love justice. But if mercy is to be received, it must first be deserved. Only when justice is honored is mercy deserved. Then, mercy becomes a joy. The person who demands mercy but denies justice destroys the only bridge over which mercy can cross.

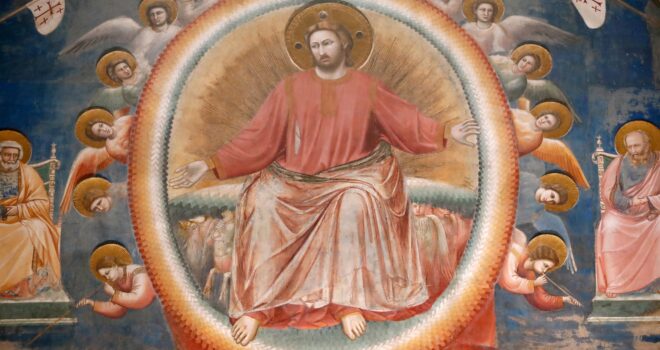

Photo by godongphotos on Shutterstock