What are the Eastern Catholic Churches? According to the Glossary of the Catechism of the Catholic Church they are “Churches of the East in union with Rome (the Western Church), but not of the Roman rite, with their own liturgical, theological, and administrative traditions, such as those of the Byzantine, Alexandrian or Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Maronite, and Chaldean rites. The variety of particular churches with distinctive traditions witnesses to the catholicity of the one Church of Christ, which takes root in distinct cultures.” Behind that definition are stories of courage, persecution, and perseverance spanning centuries and vast distances.

It is all too easy when recounting history to bog down in dates. I will try to spare the reader from a barrage of long-ago points in times past, but we must consider a few in order to grasp the saga of Eastern Catholicism. Four dates deserve to be mentioned: 1054, 1204, 1453, and 1595-6. (For a solid and well-written history of Catholicism, see James Hitchcock’s 2012 History of the Catholic Church From the Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium.) Although not the first breach of unity between the Latin West centered in Rome and the East linked to Constantinople, 1054 marks what many call “the Great Schism,” though it was actually quite limited in scope. The Pope’s delegate and the Patriarch of Constantinople excommunicated each other over matters of practice and power. Although that date marked growing misunderstanding, it was the sack of Constantinople by Western Crusaders in 1204 that provoked great anger and resentment amongst Eastern Christians, even though Eastern political intrigues had a part in the tragedy. After passing back into Byzantine hands later in the thirteenth century, the great capital of the Eastern empire fell to the Ottoman Turkish Muslims in 1453. Reports of the city’s final hours tell of both Latin and Eastern clergy joining together in Hagia Sophia to celebrate the Sacred Liturgy. The conquering Islamic tide that had begun in the seventh century continued to swallow up much of the Eastern Christian world. Thus the existing separating factors between West and East were reinforced by Ottoman subjugation. Eastern Christians were mostly cut off from the Latin West.

A major turning point in our story occurred in 1595. The Roman Church, fired by the zeal of the Counter-Reformation, had been sending missionaries to the peripheries of the known and newly-discovered corners of the globe. Jesuits at work in Eastern Europe convinced some of the schismatic Orthodox of the truth of Rome’s claims to primacy. A number of bishops professed allegiance to the Supreme Pontiff and Successor of St. Peter in 1595-96. The Eastern faithful were allowed to keep their liturgy and customs. From that point on, Eastern Catholics were often faced with a common dilemma: their former compatriots who had not made peace with Rome viewed them as traitors and heretics. They also faced discrimination from Latin-rite Catholics because of their different liturgy and customs. Especially controversial was the practice of the East in ordaining married men to the diaconate and priesthood (though not to the office of bishop). Further missionary efforts led to more reunions of the faithful in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. James Hitchcock provides a summary of Rome’s policy toward reunited Easterners: “After the Catholic-Orthodox split of the Middle Ages, the Holy See showed an increasing willingness to make accommodations with those Eastern Christians (sometimes called Uniates) who were in communion with Rome. The history is a complex one, but overall the official policy followed by the Holy See was enunciated by Pope Benedict XIV (1740-1758), who declared unequivocally that the Easterners had a right to retain their own customs” (206). As of 2023 there are twenty-three Eastern Churches. There is a separate Code of Canon Law for the Eastern Churches and they have their own administrative structures.

Despite these differences, the Eastern Churches offer all of us compelling examples of faithfulness. One such saint is Josaphat, a Polish-Lithuanian monk and bishop martyred by the Orthodox in 1623 for his evangelizing and pastoral efforts. On the 1962 traditional calendar his martyrdom is celebrated as a third class feast on November 14; on the new calendar November 12 is the obligatory memorial of the saint. Saint Josaphat’s life bears witness to the diversity in unity that characterizes the Eastern Catholics.

However, as previously mentioned, sometimes Latin Catholics were not welcoming to Eastern believers. Many Eastern Catholics from eastern Europe and the Middle East came to the U.S. in the later decades of the nineteenth century and early twentieth. Many came for mining work or to escape persecution. Often these immigrants found no Eastern Catholic priests to minister or provide the sacraments to them. A notorious case of religious bigotry aimed at the Eastern Catholics occurred in Minnesota in 1889. A Uniate priest, Father Alexis Toth, arrived to care for the Eastern faithful. The local Roman Catholic ordinary, Archbishop John Ireland, refused to accept Father Toth as a priest and dismissed him and the faithful, telling them to worship with the Latin-rite Poles. Toth and others got together and sent an emissary to the Russian Orthodox bishop in San Francisco, and eventually they were received into the Russian Orthodox Church. The parish where I worshiped in Washington state began as part of that movement. Founded by Ruthenian miners in the mining town of Wilkeson, Washington, they left communion with Rome.

Not all stories ended that way, but Eastern Catholics, while able to establish parishes in cities like Pittsburgh, often found themselves needing to go to Latin-rite priests who did not speak their language. The result is that within one or two generations they had assimilated into American culture and the Latin-rite. In my part of northern New York, there is evidence of that progression in at least two places: the former mining town of Lyon Mountain, and the former lumber-producing Adirondack village of Tupper Lake. Lyon Mountain, in the northern periphery of the Adirondacks, produced high grade iron ore for many years. With their mining expertise, many workers from the Carpathian Mountains came to work in Lyon Mountain. There was never any Eastern Catholic church built for them. Today they are buried in the cemetery behind St. Bernard’s in Lyon Mountain. Some of the grave markers feature Cyrillic writing. The Tupper Lake story involves Maronite Christians coming there from Syria and Lebanon. Again, no church was built for them and today their descendants attend Roman Catholic parishes in the region.

The largest Eastern Catholic body today is the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), which has an almost-unbelievable history. Under the Soviet Union, the UGCC was persecuted and finally declared defunct and suppressed by the Soviets in the 1940s. The UGCC property was given to the Russian Orthodox Church, which at the time was collaborating with the Soviet authorities. Only with the fall of the USSR did the UGCC emerge from the underground to reclaim its place in an independent Ukraine. Their struggle produced a host of martyrs and heroes of the faith. Those struggles also produced a large Ukrainian Greek Catholic diaspora, especially in Canada.

It’s quite likely that the typical Catholic in the U.S. lives far from any Eastern Catholics, and that is a shame. Our Eastern Catholic brothers and sisters are a living testament of faith, tradition, and perseverance. Engagement with our fellow Catholics might teach us about other cultures and traditions, but with a shared devotion to Our Lord, Our Lady, and the saints. In these challenging times, we would do well to get acquainted.

✠

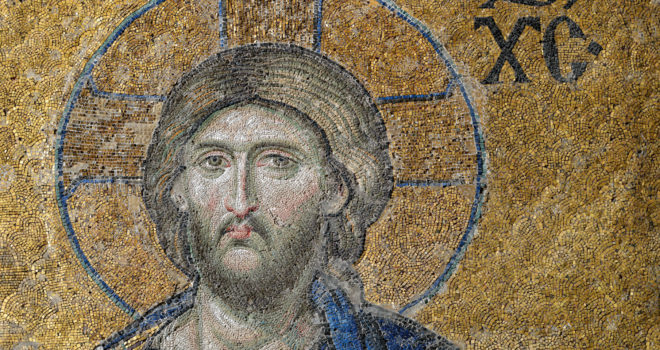

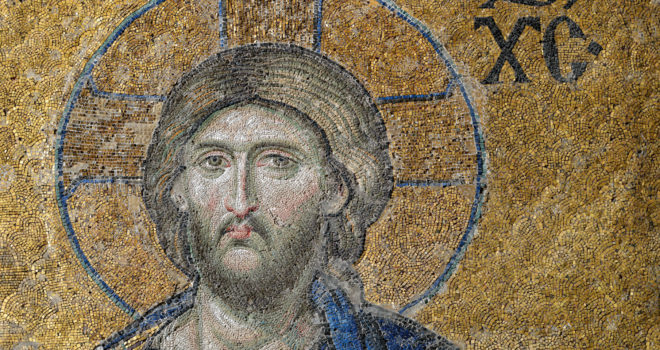

Image by gd_project on Shutterstock