Viewing and pondering sacred art offers the faithful a great way to meditate more deeply on the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. This series of articles will highlight several pieces of art related to the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary, which highlight Our Lord’s public ministry. Each of these pieces of art allows us to reflect on Jesus’ teachings and miracles, connecting them more fully to our own lives.

The Fifth Luminous Mystery is Jesus’ institution of the Eucharist, the moment that he commanded his followers to eat his flesh and drink his blood. St. John Paul the Great, in his apostolic letter on the Rosary, tells us that it is in this event that Jesus “testifies ‘to the end’ his love for humanity (Jn. 13:1), for whose salvation he will offer himself in sacrifice” (Rosarium Virginis Mariae, 21). In this moment, the Light of the World passes on his light to others, in his own sacramental flesh, so that they could become “the light of the world” as he had called them during the Sermon on the Mount.

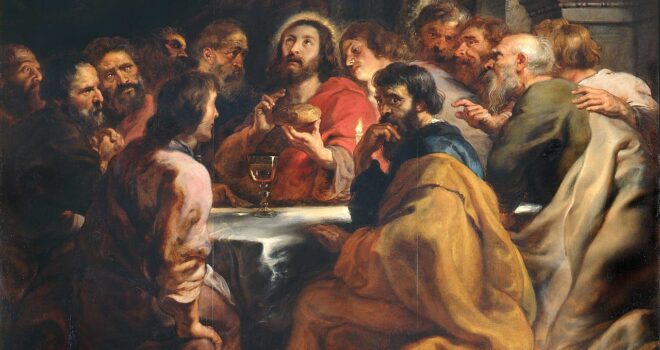

Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish Baroque artist with whom we began this series of reflections, completed his depiction of this event, Last Supper, in 1630 and 1631. Originally created as part of an altarpiece for a Belgian church, this painting offers several captivating details about the Eucharist. It especially provides a rich opportunity to reflect on the theme of light, specifically our capacity to live as the light of the world.

Jesus, of course, is the focal point of this painting. His position and his gaze bring the viewer into a palpable sense of close proximity in this moment. As the Messiah turns his eyes heavenward, we can almost hear his high priestly prayer recorded in John 17: “Father, the hour has come; glorify your Son that the Son may glorify you…” (Jn. 17:1 ESV). This depiction of an intensely intimate moment ought to provide a font of ongoing relationship with the Father, whose every action is intended and used to draw close to humanity.

Jesus holds a small loaf of bread in His left hand above a chalice. These are the species that were transformed at that First Eucharist, and continue to be transformed at each Mass throughout history. His right hand is raised in the gesture of a blessing, which is an essential action that has confected the Blessed Sacrament throughout all generations. When a viewer sees this detail, the words of institution over the bread and chalice quickly come into our minds and hearts (see Lk. 22:19-20). Rubens’s depiction of the species and the sacred action ought to bring each of us to a deeper devotion to the liturgy, as well as the sacred vessels and offerings that are presented to God for transformation.

Another important detail augments this point, but it might escape us without close examination. As Jesus raises his eyes to Heaven and holds the bread in his hand, a shaft of light pierces downward onto Him and the eucharistic species. This is surely representative of two things: the action of the Holy Spirit to transform the bread and wine (epiclesis); and the relationship of intense love that exists within the Trinity. Again, a viewer is brought into this intimate exchange of love and power. The viewer is now capable of taking on the light and power of that are available through relationship with Jesus.

Continuing with the motif of light, we notice a single candle in the middle of the table, next to Jesus’ left arm. This candle emits light that illuminates the bread and the apostles closest to Jesus. This could be significant of candles employed during liturgies, but it also holds a more general connotation. The Light that comes into our midst spreads out and transforms those who draw near. Am I in a habit of drawing near to the Light?

The apostles gathered around the eucharistic table extend the motifs of light and heavenly relationship even further. Some, like St. John the Evangelist, bear a greater degree of illumination. Others of them match the Lord’s gaze heavenward. Some of them, while illuminated and looking at Jesus, remain perplexed, as if they are skeptical of what he says. Do I allow myself, my life, to be illuminated by the light that Jesus brings? Do I look at Jesus skeptically, doubting the full truth and implication of what he says? Do I follow his gaze?

The most notable figure around the table is Judas, who looks away from the Lord and directly at the viewer. Unlike the other apostles, he has turned away from the light provided by this eucharistic moment. He bites his knuckle while bearing a look of grave concern on his face, as if to ask the viewer if he should continue with his sinister plan. There is so much about this depiction of the betrayer in this moment that aids an examination of conscience. Have I deliberately removed myself from the Eucharist and other sacraments? Even if I have attended Mass each week, have my attentions been on something less important away from the altar? Have I persisted in sinful decisions out of pride, envy, or greed? What causes me to turn away from the light that Our Blessed Lord emits?

Another interesting detail is the dog that rests under Judas’ feet. Throughout the history of art, dogs have typically represented fidelity and loyalty. Yet, in this painting, even the dog bears a cynical look on his face. Perhaps Rubens included this figure in a stroke of cynicism and irony, intending the dog to represent greed or envy, those loyalties of Judas that led him to betray Jesus for thirty pieces of silver. Each person who looks at this painting ought to ponder his own fidelity and loyalty: Am I faithful and loyal to my Lord, his Church, and the vocational call he has given to me? Am I greedy or envious of others’ victories and benefits?

Finally, at the top-right of the painting, there is an open book whose inscription reads, “Memoriam fecit mirabilium suorum, escam dedit, etc.” This is the Latin text of the first words of verses four and five of Psalm 110 in the Vulgate Bible (Psalm 111 in newer English translations). That passage reads, “He has caused his wondrous works to be remembered; the Lord is gracious and merciful. He provides food for those who fear him; he remembers his covenant forever” (Ps. 111:4-5). The inclusion of this passage is clearly meant to show the viewer that this event is the fulfillment of the old covenants. It is by the Eucharist that the “wondrous works” of the Lord are remembered; the Eucharist is the food Our Blessed Lord provides for “those who fear him.” A viewer will also quickly notice the two lit candles atop large candelabras, which continues the theme of light in this painting. The Word of God, the Bible, is another source of light that emanates from the Divine Source.

So, Peter Paul Rubens has employed light in a number of ways to help viewers understand Jesus as the Light of the World. Last Supper draws viewers into the intimacy of the Trinity and the Church at worship as the sources of that light. It also creates an opportunity for each of us to examine the dispositions and actions that might take us away from the Lord. Ultimately, a painting like this one, like the Blessed Sacrament it depicts, helps us to become the light that each of us is called to be.