The Shroud of Turin is known throughout the world. There are, however, other burial cloths said to be from the time of Christ and directly related to the Passion and death of Our Lord. Other than the Shroud of Turin, however, only one of these purported relics has an image upon it and that is the Holy Veil of Manoppello.

In a remote Italian village of Manoppello there is a cloth which until recently was largely unknown to the majority of Christians. A body of research has been growing, however, on this cloth that seems to point to the material having properties not fully understood.

The Holy Veil of Manoppello: The Human Face of God by the German journalist and historian Paul Badde is his latest work on the Holy Veil. His earlier books The Face of God: The Rediscovery of the True Face of Jesus and The True Icon: From the Shroud of Turin to the Veil of Manoppello were the first in modern times to examine the claims surrounding the Holy Veil, not least some of its intriguing links to the Shroud of Turin.

This latest work is essentially an update on where that research is today and some of the more recent events connected to the cloth, in particular, the controversial 2005 visit to Manoppello by the then reigning Pope Benedict XVI.

The modern story of the Veil starts with an earthquake on 13 January 1913. The four quakes on that day reportedly killed an estimated 30,000 people. One of the buildings damaged in these quakes was the Church of St. Michael on the Tarigini Hill just by the gates of Manoppello. This was a small and, in worldly terms, insignificant church entrusted to the Capuchin order. In that church since 1638, there had lain an obscure object of devotion, one held in a fortified case, secured by three padlocks and placed in a side chapel. Only twice a year was this object exhibited to pilgrims.

How that object got to Manoppello in the first place was not fully known. There was a laconic inscription inside the church that simply told of a local pharmacist donating it to the Capuchin order at Manoppello in 1638.

In 1923, during the much-needed church restoration that followed the earthquake, the new guardian, Fr. Roberto, moved the relic to a place where, via a newly installed staircase, it could be viewed and venerated by pilgrims. One of those to do so in October 1964 was a Capuchin friar, named Fr. Domenico.

Not far from Manoppello, the then ten-year-old boy, Emidio Petracca, was nearly killed alongside his father while assisting Holy Mass on the morning of one of the 1915 earthquakes. Later, he was pulled to safety from the rubble by an unknown rescuer. Eventually, in 1922, Petracca entered religious life as a Capuchin. It was not until 50 years later, however, that Emidio, now Fr. Domenico, made a pilgrimage to Manoppello. On that occasion, he mounted the stairs to venerate the cloth. He found himself stunned by what he saw in front of him. Standing before the veil displaying what was reputedly the Holy Face, all the priest could stammer was: “This is the man who pulled me out of the debris fifty years ago! He is the one who saved me! It is He!”

From that day on Fr. Domenico became known as the Apostle of the Holy Face. Not only did he study all that he could find that had been written on the Holy Veil, but he also asked his Capuchin superiors that he might be transferred to the shrine at Manoppello, which duly happened. Thereafter, he was to be seen praying night and day in front of the Holy Face.

Soon Fr. Domenico had made a new claim for the cloth. He suggested that it was the Sudarium of Christ, the very veil that had lain over the head of the Crucified Lord, one of the cloths referred to in the Gospel of St. John seen in the tomb by St. Peter and St. John. There are a number of other burial cloths that some have claimed also came from the tomb that morning. They are scattered throughout Europe, found at Turin, Oviedo, Occitania, Kornelimünster Abbey, and Rome. The fact that there are a number of these is consistent with what we know of Jewish burial customs in the first century. Only two of the cloths, however, have images upon them: the Shroud of Turin and the cloth at Manoppello.

Unlike the Shroud, the Manoppello Veil has no trace of color or blood. That said, there was no trace of paint upon it either, nor are there any signs of it having been created as an imprint. Therefore, even to this day, the image and the cloth’s origin remain a mystery.

In September 1978 Fr. Domenico travelled to Turin to examine the Holy Shroud, then about to be exhibited to the public for the first time in 45 years. When he stood before the Shroud it is claimed that he could only marvel at what he saw, so clearly did the face upon the Shroud resemble that upon the Holy Veil of Manoppello. The difference beween the two images being that one recalled a dead figure and the other recalled the same figure but alive. The next day, while pondering this on his way back to his hotel, Fr. Domenico was struck by a car. He died a few days later in hospital. His last words were: “Venerate the Sudarium of Christ!”

As Fr. Domenico lay dying, a well-known Italian journalist arrived in Manoppello. Renzo Allegri had heard of the Veil. At that time, with the Shroud exhibition taking place, he wondered if there was a story to be found in that out of way Italian village with its lesser known relic that some claimed to be the piccolo sindone (little shroud). The subsequent article Allegri was to write for GENTE, an Italian weekly, and published just days after the funeral of Fr. Domenico, reached millions of readers in Italy and brought the Holy Veil to a national and international audience.

Not long after, another magazine published Allegri’s article in German. At this point Badde relates how a copy of the German version of the article found its way to a Trappist monastery in Switzerland. Upon reading it, one of the nuns in community there with great urgency wrote letters to two German academics who had been conducting various high-level studies on the Shroud of Turin.

From here the story widens and deepens. Badde weaves a tale involving history and science, not least the surprising discovery of marine bysuss in the veil. This fabric was the ancient world’s most precious. It is also a fabric to which it is impossible to apply paint. The Holy Veil of Manoppello also tells of a Jewish Rabbi’s remarkable vision concerning the Veil; and of the unexpected announcement in 2011 from the Director of the Vatican Museums admitting that an ancient relic pertaining to the Holy Face had disappeared from Rome during the Lutheran sacking of the city in 1527. This disclosure set off a different line of inquiry for Badde regarding the Veil. The book asks if the Veil is the same cloth as that used by Veronica, the woman depicted in the Sixth Station of the Cross wiping the face of Christ. Badde tells of skeptical professors who become enthusiastic campaigners for the Veil’s authenticity, of the links between the Veil and ongoing research into the Shroud. Throughout, Badde conveys the drama and the mystery at the heart of the story he tells.

In some ways the culmination of this story comes on 1 September 2006. Badde claims that this day saw the first pope since St. Peter behold the Holy Veil. On that pilgrimage, in the teeth of hostile opposition from within the Roman Curia, Pope Benedict knelt in prayer before the Veil of Manoppello.

Six days later, at his general audience in St. Peter’s Square, Pope Benedict said the following:

“We can truly say that God was given a human face, that of Jesus, and henceforth, if we really want to know God’s face, we have only to contemplate the face of Jesus!”

Editor’s note: The Holy Veil of Manoppello: The Human Face of God is available from Sophia Institute Press.

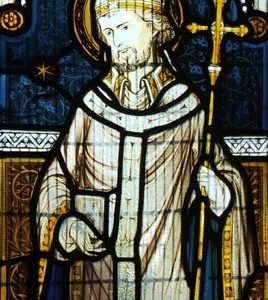

image: Holy Veil of Manoppello, courtesy of Paul Badde and Sophia Institute Press.