Viewing and pondering sacred art, engaging in vizio divina, offers the faithful a great way to meditate more deeply on the life of Jesus Christ and the mystery of salvation. This series of articles will highlight several pieces of art related to the season of Lent, specifically the Gospel readings for each week. Each of these pieces of art allows us to reflect on the transformation to which our Lord calls us during this penitential season, and to bring the realities of these biblical episodes into our own lives.

On the Fifth Sunday of Lent, in Year A of the lectionary cycle, the Church presents to the faithful the account of Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead. Outside of the Passion narratives, this is the longest narrative of a single episode anywhere in the Gospels. It is appropriate for this particular week of the liturgical year as we are drawing so near to Jesus’ Paschal Mystery, which has the potential to raise us from death to new life.

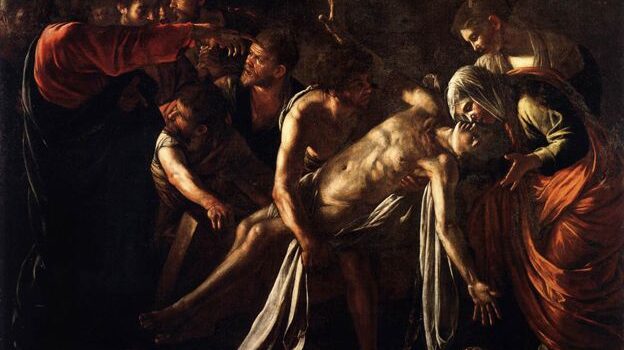

Michelangelo Caravaggio is one of the most notable names in the history of western art, as he produced some of the most recognizable paintings of the Italian Renaissance. The Raising of Lazarus, which Caravaggio painted in 1609 near the very end of his life, displays several of the artist’s most recognizable methods and motifs. In his typical manner, Caravaggio masterfully captures an intense moment, and gives viewers quite a bit to ponder.

Light floods this scene from the top-left corner of the painting. The figures in the scene are all illuminated by the light to a significant degree, especially those who are turned toward the light. This gives visual expression to the truth that God is the source of all light in this world, and that we become enlightened by turning toward Him. The season of Lent is about seeking and finding greater illumination, even through sacrifice and suffering. How have I turned toward the light by prayer, fasting, and almsgiving? Can I put words to specific ways that I have been enlightened?

At the left-hand edge of the painting stands Jesus Christ, with his outstretched arm and his finger pointing toward Lazarus. Art enthusiasts, or even novices, might quickly notice that Jesus’ position and gesture are a mirror image of another well-known Caravaggio painting, The Calling of Saint Matthew. This detail lets viewers know that Caravaggio was painting a parallel between the raising of a dead person to life and the conversion of a sinner. With his brushstrokes, Caravaggio was teaching the principle that God’s greatest miracle is, in fact, the conversion of a sinner. This idea is ripe for pondering through the remainder of the Lenten season: How have I been raised to a new spiritual life? How has Jesus drawn me closer to himself during any given day, week, or season?

On the opposite side of the painting are Mary and Martha, the sisters who “sent word to Jesus” of Lazarus’s illness (Jn. 11:3). Leading up to this moment, these women have been restlessly worried about their brother’s health, which is why Mary says to Jesus, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died” (Jn. 11:32). This might cause a viewer to ponder: Are there any human, worldly situations that have occupied my attention and energy too much? How can I learn to entrust those situations to the Lord who holds all history in his sacred hands?

At the visual center of this scene is Lazarus, the man who was raised from the tomb. Lazarus is in a cruciform position, but at an angle. His right hand reaches toward the light, while his left hand is almost touching a skull (which seems to have been brought out of the tomb with him). This signifies that all of human life bears the possibility of divinization at the same time that it bears the possibility of eternal death. We must rely on the God-Man to provide us with the former and rescue us from the latter by his grace. As one gazes on this part of the painting, some appropriate questions come to mind: How have I reached out for the passing things of this world? How have I reached out toward the divine light that is available to me? How has that light divinized me, even in part?

We note also that the “burial bands” that had Lazarus “tied hand and foot” as well as the cloth that wrapped his face (Jn. 11:44). In this moment, those trappings of death are nearly removed from Lazarus, but they are still apparent. This simple detail reminds us that our lives are perpetually facing the “bondage to corruption” about which St. Paul writes in his letter to the Romans (Rom. 8:21). How are my body and mind in bondage to corruption? To what degree has God removed the proverbial burial cloths that are wrapped around me by my actions; or have been wrapped around me by the actions of others?

Because Lazarus was not fully able to stand on his own at this moment, his body is held by a man while Mary, his sister, holds his head and caresses his cheek with hers. Even while Lazarus has been raised from the dead, he still relies on the support of others. This detail serves to remind viewers that each of us needs community to care for us and hold us up. Our Christian life is intended to be one of giving and receiving care and support. This ought to cause each of us to reflect on where community is present in our lives. Have I helped others learn to stand more surely in the spiritual life? Have I allowed others to help me gain surer footing? Have we shown each other the love that Jesus had for Lazarus, Mary, and Martha?

Behind Jesus and Lazarus are the other witnesses of this miraculous event. Their faces bear looks on a spectrum between bewilderment and awe. Some look directly at Jesus, while others look at Lazarus. Nearly all the figures in the scene are illuminated by the source of light that comes from outside the scene. Caravaggio clearly intends to depict those “who had come with Mary and had seen what he did [and] believed in him” (Jn. 11:45). This detail may cause those who reflect on this painting to ask: What has been my response when I have witnessed great miracles, especially the conversion of sinners? Am I incredulous, or does their conversion bring me to greater faith in the power of God?

In conclusion, Caravaggio’s The Raising of Lazarus is a piece of art that superbly draws viewers into the themes of Lent, and it is an image that should be pondered as we enter into these last weeks of this penitential season. It reminds us that God, in the person of Jesus Christ, can raise the dead, even the spiritually dead, to new life. It reminds us that our whole life on this earth is a constant struggle between grasping at the vanities of this world and reaching toward the divine light that is offered from beyond this world. It reminds us of the importance of community in being lifted from and kept out of the grave of sin. If we gaze on Caravaggio’s painting and remember these themes, the final days of Lent are sure to be quite fruitful.

✠

The Raising of Lazarus is in the public domain.