Recently, I was asked to preach an anointing of the sick scenario in my homiletics class. The topic of illness and suffering called to mind one of my favorite books by C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain. Most people know Lewis from his Narnia series, especially The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, but he also wrote popular works of theology and philosophy, including The Problem of Pain in 1940. The problem to which the title alludes is not with pain itself, but with why God allows so much of it. If God is all-powerful and all-good, why is there so much suffering and wickedness in the world? Why doesn’t God intervene, at least to prevent some of the worst instances of physical and moral evil? For many an atheist, the problem of pain is a trump card against God, as it was for Lewis before his conversion, and even devout religious believers find it troubling. Lewis wrote the Problem of Pain to think through how best to address this perennial challenge to faith.

Lewis’s book is well worth reading, but his approach is more philosophical than pastoral. He argues, for example, that to be free we need a world with stable laws, because we cannot act unless we can first anticipate how our environment will respond. But stable laws mean the possibility of pain. The sun has a stable nature, which allows farmers to grow crops, but it also means that if we’re out in the sun too long, we’ll get burnt. Moreover, Lewis argues that if we are to be meaningfully free, then God must respect our choices, including our bad ones. If God only allows me to praise my neighbors but never curse them, then I’m not really free. Such arguments have their place, no doubt, but they bring little comfort when we hear about destructive earthquakes or university shootings.

Lewis himself came to see the limitations of philosophy in the face of great suffering. When he wrote The Problem of Pain, he was a bachelor living a comfortable academic life. Then he met a woman, an American named Joy, and eventually they were married. (Their rather unusual love story is depicted in the movie Shadowlands.) For a time, they were profoundly happy, but in 1957 Joy was diagnosed with cancer and she died three years later. Lewis then experienced a pain he never thought possible, and he wrote a second book on the topic called A Grief Observed, in which he turned to faith rather than philosophy to grapple with his loss. He doesn’t repudiate what he wrote earlier; rather, he comes to recognize philosophy’s ultimate limitations for addressing the existential state of one who is suffering greatly.

Like the early Lewis, I think that philosophy has an important role in addressing the problem of pain. But like the later Lewis, in my own experiences with suffering, I turn to faith. Specifically, I turn to two truths of faith, which build upon and transcend the resources offered by philosophy. First, God always has a reason for allowing evil and suffering, even if we’ll never know the reason. This is the great lesson of the book of Job. Job is a righteous man who suffers tragedy after tragedy and cries out to God for an explanation. God then appears, and rather than explain why He has allowed Job to suffer, He simply reminds Job that He is God and Job is not. And this comforts Job. He glimpses the truth that God never allows an evil unless He can bring some greater good from it.

The second truth of faith, and this really is the heart of Christianity, is that the Son of God, who is God, became a man and suffered and died for our sins. It’s a mystery why God would create a world with so much suffering, but an even greater mystery that He would want to share in our condition and suffer for us. And suffer He did. Jesus suffered every kind of pain imaginable. Physical pain, obviously, of the worst sort. He was beaten and scourged and crowned with thorns and crucified. But He also suffered emotional pain. He was abandoned by his closest friends and ridiculed by His enemies. Finally, and worst of all, Jesus suffered great spiritual pain. As God, He surely knew that some of His efforts would be lost on those who persist in sin, and as man, He experienced the abandonment of God the Father on the cross just before His death. And all this out of love and compassion for us.

The anointing of the sick, perhaps the least understood of the Church’s sacraments, conforms us in a powerful way to the suffering of Jesus Christ. Thus, it has deep ties to the sacraments of baptism and confirmation. When we are baptized, we are anointed with oil and configured to Christ by being given a share in His divine life. When we are confirmed, we are anointed again, and this configures us to Christ more deeply by giving us the strength to be a soldier for Christ. When we receive the anointing of the sick, we are anointed with oil yet again, and this binds us in a special way to the redemptive suffering of Christ. The remarkable thing about Christ’s suffering is that He made it the vehicle for humankind’s salvation, and when we join our suffering with His, we participate in His redemptive suffering. This, I would posit, is faith’s ultimate answer to the problem of pain, as Pope St. John Paul II explains so beautifully in his encyclical Salvici Dolores:

Christ does not answer directly and he does not answer in the abstract this human questioning about the meaning of suffering. Man hears Christ’s saving answer as he himself gradually becomes a sharer in the sufferings of Christ. The answer that comes through this sharing, by way of the interior encounter with the Master, is in itself something more than the mere abstract answer to the question about the meaning of suffering. For it is above all a call. It is a vocation. Christ does not explain in the abstract the reasons for suffering, but before all else he says: “Follow me!” Come! Take part through your suffering in this work of saving the world, a salvation achieved through my suffering! Through my cross. Gradually, as the individual takes up his cross, spiritually uniting himself to the cross of Christ, the salvific meaning of suffering is revealed before him (Salvici Dolores, § 26).

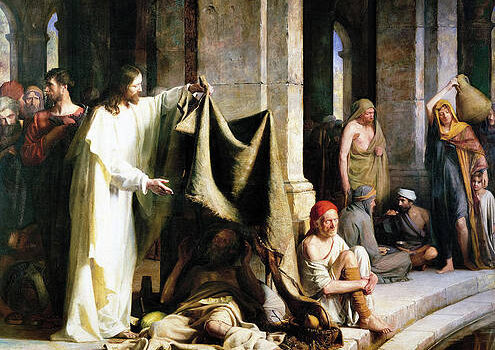

Image: Christ Healing the Sick at the Pool of Bethesda, Carl Bloch. Public domain.