Viewing and pondering sacred art, engaging in vizio divina, offers the faithful a great way to meditate more deeply on the life of Jesus Christ and the mystery of salvation. This series of articles will highlight several pieces of art related to the glorious Easter season, with specific attention to Scripture readings. Each of these pieces of art allows us to reflect on the astonishing realities of the resurrected life.

Each year on the Second Sunday of Easter (known as Divine Mercy Sunday since the Great Jubilee Year 2000), the Church proclaims the Gospel passage in which the apostle Thomas, known to posterity as “Doubting Thomas,” sees and touches Jesus’ scars from the crucifixion. Without a doubt, it is one of the Gospel episodes that has the greatest impact on the faithful, perhaps because they realize just how much they are actually like the incredulous apostle.

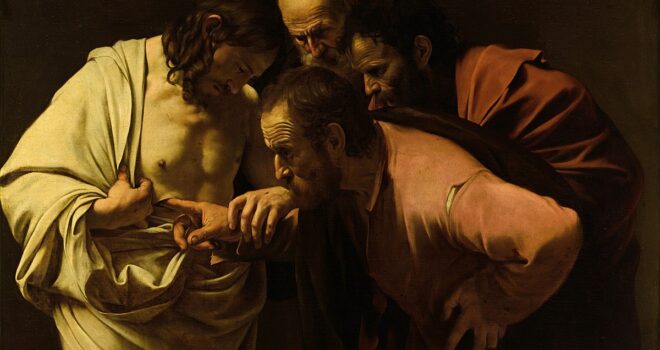

In the first years of the seventeenth century (1601 and 1602), Michelangelo Caravaggio painted The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, another of his well-known masterpieces. There are very few details in this painting, which allows a viewer to meditate on a few points very deeply. That is why this Renaissance masterpiece makes such a powerful statement of spirituality.

The very first thing that a viewer notices as she approaches this painting is Caravaggio’s masterful use the chiaroscuro technique, employing light and shadow for deeper artistic effect. Throughout Caravaggio’s work, and in this painting particularly, this technique causes a viewer to reflect on the presence of spiritual light and darkness in his own life.

Along with the use of chiaroscuro, the background is completely dark. This does two things. First, it allows the viewer to be drawn in to an intensely intimate moment in the life of a disciple and the Church. Second, the dark background allows the viewer to generalize and bring the scene to his or her own life. It causes the viewer to question: Have there been times in my life when I have obstinately refused to believe Jesus’ revelation without apodictic evidence?

At the forefront of the group, we notice Thomas, hunched over, looking intently, and placing his finger in the lance wound in Jesus’ side. It is hard to see (easier in the “Ecclesiastical Version” from 1601), but Thomas has been wearing a dark colored cloak. At the moment captured in this painting, the cloak is already halfway removed, and it seems to be falling off the rest of the way. This ought to remind us of the tandem work, the unity, of reason and faith in arriving at a full understanding and appreciation of truth. Thomas, as a stalwart of empiricism, has only shed half the cloak of darkness. Even Jesus says as much to him: “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (Jn. 20:29).

Then, the look on Thomas’s face brings us even more deeply into this astonishing moment. His eyes pop open wide, and his brow is furrowed in surprise, creating lots of wrinkles. The viewer is almost able to hear his reaction recorded by St. John the Evangelistt: “My Lord and my God!” (Jn. 20:28).

When we look at Thomas’s hand, we notice another hand guiding the doubter’s hand. Jesus told Thomas to “put out your hand, and place it in my side” (Jn. 20:27). The artist makes visible the Lord’s command, and his desire to be known fully. This detail, which seems so obvious and simple, reminds us that it is the Lord’s grace that opens up our relationship with him, that leads us to knowledge of himself and of the universe. Do I allow Jesus to direct me toward the evidence and answers I seek? Do I realize that all of that knowledge is meant to lead me closer to him?

While considering the position of Thomas’s hand, it is easy to notice both of Jesus’ hands. These are the scars of the crucifixion, which, in the words of Ven. Fulton Sheen, Our Blessed Lord “bears now and forevermore…as pledges of love and forgiveness.” Have I spent time meditating on scars? How are scars able to foster deeper relationship and love? Do I realize that Jesus looks at me through his scars? What about my own scars and relationship with others?

Beyond the scars on Jesus’ hands, we notice that Our Lord is the most luminous figure of the four depicted. While he does not seem to be the source of light in this painting, this fact captures our Catholic belief that Jesus is the recapitulation of all God’s saving words and actions throughout the history of the old covenants (see Catechism of the Catholic Church 430).

Behind Jesus and Thomas are two other figures. Based on the biblical text, we can assume that these are two of the apostles gathered in that upper room. Still, the fact that they are not specifically identified provides two avenues for deeper reflection. The first avenue is that these figures represent any one of us as disciples of the Lord. Do we watch as other disciples try to meet Jesus and grow in relationship with him? Are we impacted positively or negatively by their efforts?

The second avenue for consideration is that these men stand for the visible Church. Throughout the centuries, the Church has stood close in the background watching and approving the probing work undertaken to advance empirical knowledge of God and the universe. This has been true in theology, philosophy, and the natural sciences. Do I trust the judgment of the Church when it comes to the definition of truth? Do I believe that the Church can help me find truth in either the natural or the spiritual realms?

So, as we recall this memorable post-Resurrection event during the Easter season, let’s all hope that, with St. Thomas, we can learn to discover and appreciate the saving wounds of Jesus. Let’s also hope for the divine grace that heals all wounds. Let’s lift up and celebrate the diligent work that the Church has always done to foster greater knowledge of all scientific, historical, and theological truth. Most of all we should hope remain where Jesus wants to bring us, to his wounded side and his Sacred Heart.