Viewing and pondering sacred art, engaging in vizio divina, offers the faithful a great way to meditate more deeply on the life of Jesus Christ and the mystery of salvation. This series of articles will highlight several pieces of art related to the season of Lent, specifically the Gospel readings for each week. Each of these pieces of art allows us to reflect on the transformation to which our Lord calls us during this penitential season, and to bring the realities of these biblical episodes into our own lives.

We are in the midst of the holiest week of the year, which was inaugurated on Palm Sunday and proceeds through the liturgies of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter Sunday. These days are our very own participation in the Paschal Mystery of Jesus. By these celebrations, the most central mystery of our faith is re-presented to the faithful, and we are drawn into the upward trajectory of our salvation and redemption.

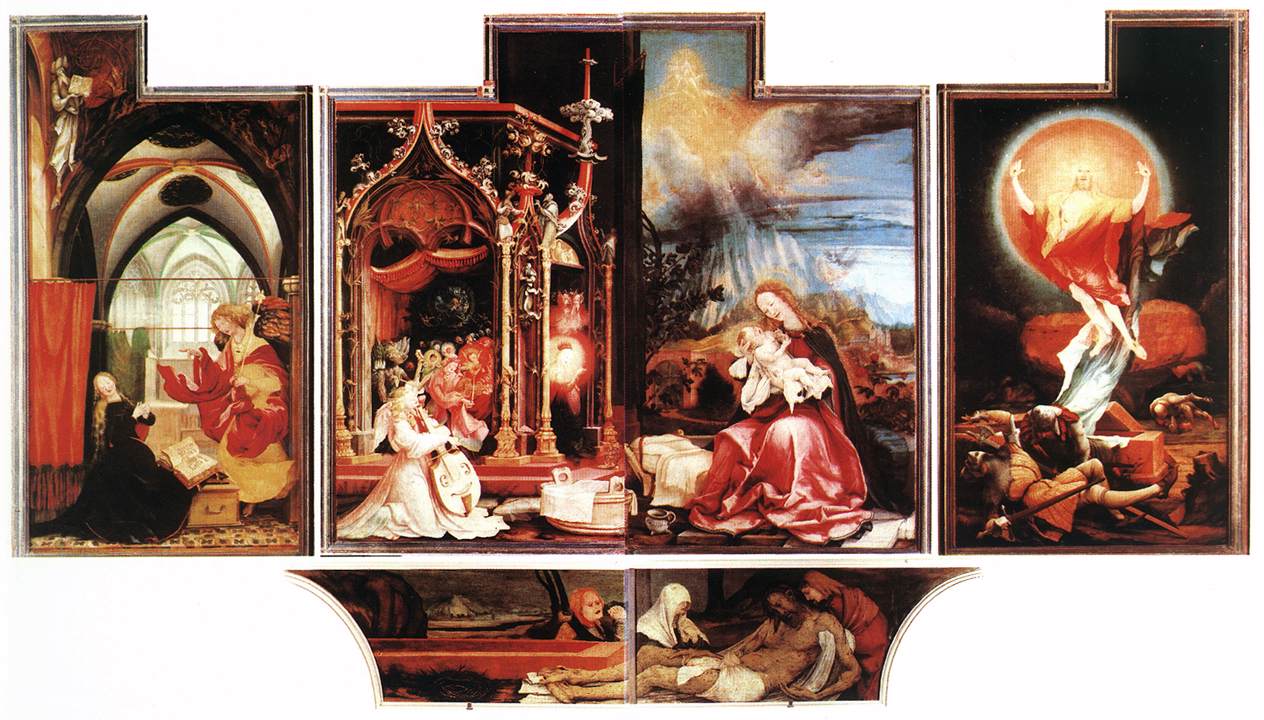

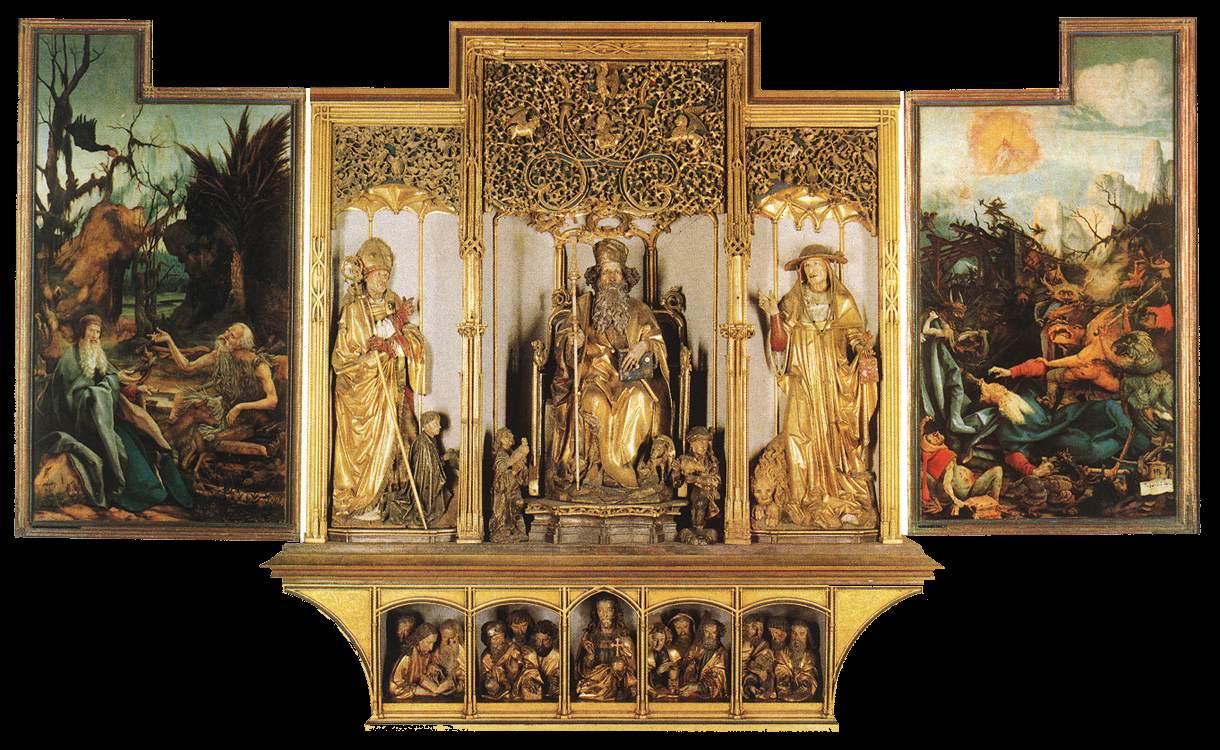

Between 1512 and 1516, Nikolaus Hagenauer, a sculptor, and Matthias Grünewald, a painter, crafted an altarpiece for a monastery in Isenheim, France. The whole altarpiece presents three different views, along with sculptures, for three different types of liturgical occasions. The best-known view, which is the focus of this essay, is the painting at the center of the altarpiece when it is closed fully. Grünewald uses this central painting and the predella below it, with poignant detail and color, to bring viewers more deeply into the pain, sorrow, mystery and power of Holy Week. It leads them to the glory of Easter as it presents those events in a downward trajectory.

At the top-center of the first triptych, a viewer readily notices the crucified Christ. This part of the painting allows viewers to enter more deeply into the mystery of Jesus’ Passion and Crucifixion. The Messiah is clearly suffering, as his emaciated body hangs, contorted and bleeding. This detail causes us to realize that the events of Holy Week are, in fact, a painful experience of suffering and loss. The Passion and Death of Jesus are altogether different from ordinary human experience. At the same time, they are both harrowing and beautiful. These are the realities and emotions we experience when we enter into the liturgies of Palm Sunday, Holy Thursday, Good Friday, & Easter. Each of us might ask: Have I allowed myself to feel the movements of Holy Week on a visceral level, beyond the intellectual? Do I understand that pain and suffering can be doorways to beautiful joy?

One other detail about the crucified Christ is significant. We notice that his skin is covered with black spots. This gives expression to the Black Plague, which was a difficult time of great suffering in European history. The monks at this monastery in Isenheim had tended to the plague centuries prior. Aside from that historical reality, this detail also gives artistic expression the fact that sin is a spiritual and moral plague. The artist clearly intended to echo St. Paul’s words in his second letter to the Corinthians: “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor. 5:21 ESV). Jesus has borne our plague of sin and death so we have the opportunity to live.

On the right of the scene is St. John the Baptist, wearing a red garment symbolic of his martyrdom at the hands of Herod the tetrarch (cf. Mt. 14:1-12). In his left hand, the Baptist holds an open book. This is quite likely meant to reference the prophets of the old covenants, of whom the Baptist is last in line. He points directly to the Crucified Lord as was his mission, recorded in the Gospels. At John’s feet is a lamb whose blood drips into a chalice. Clearly, each of these details is meant to remind viewers that John was the one who exclaimed, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (Jn. 1:39). Do I allow St. John’s words to continually resound in my mind and heart, especially during Holy Week? Do those words remind me that Jesus, the “lamb that is led to the slaughter” (Is. 53:7) is the source and author of my salvation?

On the left side of the scene, we first notice the woman draped in white. This is Mary, Jesus’ mother, whose garment signifies her purity. Her hands clasped in prayer, with her eyes closed, she leans back as though she may have fainted in sorrow. This image has the potential to bring viewers to a deeper devotion to Our Lady of Sorrows. Do I find a deeper understanding and connection as I walk the movements of Holy Week with the sorrowful mother?

The figure who holds Jesus’ sorrowful mother is St. John the Evangelist, the only apostle who remained with the Messiah throughout his Passion. That John holds and protects Mary is symbolic of Jesus’ words from the cross to those two: “Woman, behold, your son!” and “Behold, your mother!” The apostle himself commented, “And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home” (Jn. 19:26-27). Have I beheld the purity, charity, and devotion of the Blessed Mother? Do I realize that her devotion is for me as much as it is for her divine Son. Have I brought her habit of pondering things in her heart (cf. Lk. 2:51) into my own soul?

The final figure depicted here, who remained with Jesus throughout his execution, is Mary Magdalene. She wears a pink garment while she kneels at the foot of the Cross, with her hands folded in prayer. Her garment is a hybrid color of the red and white that others wear in the scene. She took up a life of purity after her conversion. She also took up a life of radical devotion, which may have caused a social martyrdom. Am I like Mary Magdalene as a disciple? Do I have radical devotion to Jesus because of the way that he has transformed me, as he transformed Magdalene?

Below the Crucifixion scene is the predella of the altarpiece. This particular predella depicts the Lamentation of Jesus, the moment when the crucified Lord was laid in his tomb, which was a common motif in early-Renaissance painting. Viewing this part of the altarpiece leads us to reflect on the time of waiting, anxiety, and anticipation that the Blessed Mother and other disciples experienced on the day following the Crucifixion. How do I observe the Lamentation? Do I keep Holy Saturday as a time of solemn prayer and preparation?

The altar itself, which would stand below the predella depicting the Lamentation, makes the fitting conclusion of this downward trajectory through the Sacred Triduum. This painting, which presents the Paschal Mystery of Jesus in visual form, serves as ornamentation that fosters the very worship of the Church. It is the altar, whether in Jerusalem or Isenheim or anywhere else, upon which the Eucharistic Lord will be made present, the Risen Christ whom we receive in the Panis Angelicus. The Eucharist is the culmination of what Grünewald painted. The Eucharist is the pinnacle of the Paschal Mystery, the ultimate Easter reality, for it is the flesh of the resurrected Jesus that is offered to the faithful for the redemption of our own bodies and souls.

Here’s hoping that all of us are able to enter more fully into the mystery of Holy Week and Easter!