The time is sunset — that dread day when at high noon the sun hid its light at the passing of Light. The holy body that was purpled with blood from the precious wardrobe of His side, was now at death, laid in a stranger’s grave, as at birth it was cradled in a stranger’s cave. The rocks, which but a few hours before were shattered by the dripping of His red blood, now have gained a seeming victory by sealing in death the One who said that from rocks He could raise up children to Abraham.

In the last rays of that setting sun, which, like a eucharistic Host, was tabernacled in the flaming monstrance of the west, picture three men, a Hebrew, a Roman, and a Greek, passing before the grave of the One who went down to defeat and stumbling upon the crude board nailed above the Cross that very afternoon. Each dimly reads in his own language the inscription “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.”

The variety of languages, symbols of a variety of nationalities, provokes them to discuss what seems to them an important problem — namely, what will be the most civilizing world influence in fifty years?

The Hebrew says the most civilizing world influence in fifty years will be the temple of Jerusalem, from which will radiate under the inspiration of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the religion that will conquer the hearts of the gentile nations and make of the Holy City the Mecca of the world. The Roman contends that within fifty years, the most potent social factor will be the city of Rome, destined to be eternal because it was founded by Romulus and Remus, who in their infancy were nourished by something nonhuman — namely, a wolf, which gave them their extraordinary force and their might. Finally, the Greek, disagreeing with both, argues that in the specified time, the most important world influence will be the wisdom of the Grecian philosophers and their unknown god, to whom a statue, made by human hands, was erected in the marketplace of the great Athens.

Not one of the three gave a thought to the Man who went down to the defeat of the Cross on that Good Friday afternoon. For the Hebrew with his love for religion, and the Roman with his love for law, and the Greek with his love for philosophy, there was not the faintest suggestion that He who called Himself the Way of religion, the Truth of law, and the Light of philosophy, and who was now imprisoned by rock-ribbed earth, would ever again stir the hearts and minds and souls of men. They could not agree upon what would most influence the world in the next generation, but they were all agreed that He whose blood dried upon the Cross that afternoon would never influence it.

And yet, ere the sun had risen on that third day, in that springtime when all dead things were coming to life, He who had laid down His life took it up again and walked into the garden in the glory of the new Easter morning. Ere the fishermen disciples had gone back to their nets and their boats on the Sea of Galilee, He who had announced His own birth to a Virgin now told a penitent harlot to tell Peter that the sign of Jonah had been fulfilled. Long before nature could heal hideous scars on hands and feet and side, nature herself was to have the only serious wound she ever received — namely, the empty tomb, as He was seen walking on the day of triumph with five wounds gleaming as five great suns, as an eternal proof that love is stronger than death.

Fifty years passed, and what happened? Within that time, the army of Titus struck the Temple of Jerusalem and left not a stone on stone, while over the empty tomb all the nations of the earth saw a new spiritual edifice arise, whose cornerstone was that which the builders rejected. Within fifty years, Rome discovered the real reason for its immortality; it was not because Romulus and Remus, nourished by the wolf, had come to dwell there, but because the spiritual Romulus and Remus, Peter and Paul, nourished on the Bread descended from Heaven, came there to preach the eternal love of the risen Christ. Within fifty years, the dominant spiritual force in Greece was not the unknown god made by human hands, but the God whom St. Paul announced to the Areopagites when, stretching forth his hands he said: “I found an altar on which was written: ‘To the Unknown God.’ What, therefore, you worship without knowing it, I therefore preach to you: God, who made the world and all things therein. . . for in Him we live and move and are.”

Fifty years passed, and Jerusalem would have been forgotten, had not Jesus died there. Rome would have perished, had not a fisherman died there. Athens would have been forgotten, had not the risen Christ been preached there. Fifty years passed, and the three cultures in which He was crucified now sang His name in praise. The Cross, which was the instrument of shame, became the badge of honor, as Calvary was renewed on Christian altars in the language of Hebrew, Latin, and Greek.

Christ turned defeat into victory

The world was wrong, and Christ was right. He who had the power to lay down His life had the power to take it up again. He who willed to be born, willed to die. And He who knew how to die knew also how to be reborn and to give to this poor tiny planet of ours an honor and a glory that flaming suns and jealous planets do not share: the glory of one forsaken grave.

The great lesson of Easter Day is that a Victor may be judged from a double point of view: that of the world and that of God. From the world’s point of view, Christ failed on Good Friday. From God’s point of view, Christ had won. Those who put Him to death gave Him the very chance He required; those who closed the door of the sepulcher gave Him the very door that He desired to fling open; their seeming triumph led to His greatest victory.

Christmas told the story that Divinity is always where the world least expects to find it, for no one expected to see Divinity wrapped in swaddling clothes and laid in a manger. Easter repeats that Divinity is always where the world least expects to find it, for no one in the world expected that a defeated man would be a victor, that the rejected cornerstone would be the head of the building, that the dead would walk, and that He who was ignored in a tomb should be our Resurrection and our Life.

Unroll the scrolls of time, and see how the lesson of that first Easter is repeated as each new Easter tells the story of the great Captain, who found His way out of the grave and revealed that lasting victory must always mean defeat in the eyes of the world. At least a dozen times in her life of twenty centuries, the world in the first flush of its momentary triumph sealed the tomb of the Church, set her watch and left her as a dead, breathless, and defeated thing, only to see her rising from the grave and walking in the victory of her new Easter morn.

In the first few centuries, thousands upon thousands of Christians crimsoned the sands of the Coliseum with their blood in testimony to their Faith. In the eyes of the world, Caesar was victor and the martyrs were defeated. Yet in that very generation, while pagan Rome with her brazen and golden trumpets proclaimed to the four corners of the earth her victory over the defeated Christ — “Where there is Caesar, there is power” — there swept from out of the catacombs and deserted places, like their leader from the grave, the conquering army chanting its song of victory: “Wherever there is Christ, there is life.”

Who today knows the names of Rome’s executioners? But who does not know the names of Rome’s martyrs? Who today recalls with pride the deeds of a Nero or a Diocletian? But who does not venerate the heroism and sanctity of an Agnes or a Cecilia? And so, on Easter Day, I sing, not the song of the victors, but of those who go down to defeat.

In a little city a few hours outside of Paris, a young girl hidden away in the shadow of the cloister was pouring out her prayerful life for Christ and, like her Master, going down to defeat in the eyes of the sinful world. Who does not know of the Little Flower, Thérèse of Lisieux? She who was defeated in the eyes of the world is the victor in the eyes of God, and so on Easter Day I sing, not the song of the victors, but of those who go down to defeat.

Finally the Easter lesson comes to our own lives. It has been suggested that it is better to go down to defeat in the eyes of the world by accepting the voice of conscience rather than to win the victory of a false public opinion; that it is better to go down to defeat in the sanctity of the marriage bond than to win the passing victory of divorce; that it is better to go down to defeat in the fruit of love than to win the passing victory of a barren union; that it is better to go down to defeat in the love of the Cross than to win the passing victory of a world that crucifies. And now it is suggested in conclusion that it is better to go down to defeat in the eyes of the world by giving to God that which is wholly and totally ours.

God desires our will

If we give God our energy, we give Him back His own gift. If we give Him our talents, our joys, and our possessions, we return to Him that which He placed into our hands, not as owners, but as mere trustees. There is only one thing in the world that we can call our own. There is only one thing we can give to God that is ours as against His, which not even He will take away, and that is our own will, with its power to choose the object of its love.

Hence, the most perfect gift we can give to God is the gift of our will. The giving of that gift to God is the greatest defeat that we can suffer in the eyes of the world, but it is the greatest victory we can win in the eyes of God. In surrendering it, we seem to lose everything, yet defeat is the seed of victory, as the diamond is the child of night. The giving of our will is the recovery of all our will ever sought: the perfect Life, the perfect Truth, and the perfect Love which is God! And so on Easter Day, sing, not the song of the victors, but of those who go down to defeat.

What care we if the road of this life is steep, if the poverty of Bethlehem, the loneliness of Galilee, and the sorrow of the Cross are ours? Fighting under the holy inspiration of One who has conquered the world, why should we shrink from letting the broad stroke of our challenge ring out on the shield of the world’s hypocrisy? Why should we be afraid to draw the sword and let its first stroke be the slaying of our own selfishness? Marching under the leadership of the Captain of the Five Scars, fortified by His sacraments, strengthened by His infallible truth, divinized by His redemptive love, we need never fear the outcome of the battle of life. We need never doubt the issue of the only struggle that matters. We need never ask whether we will win or lose. Why, we have already won — only the news has not yet leaked out!

Editor’s note: This article was adapted from a chapter from Ven. Fulton Sheen’s God’s World and our Place in It, available from Sophia Institute Press.

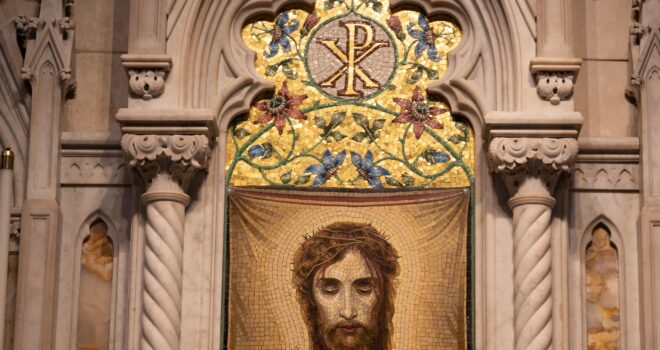

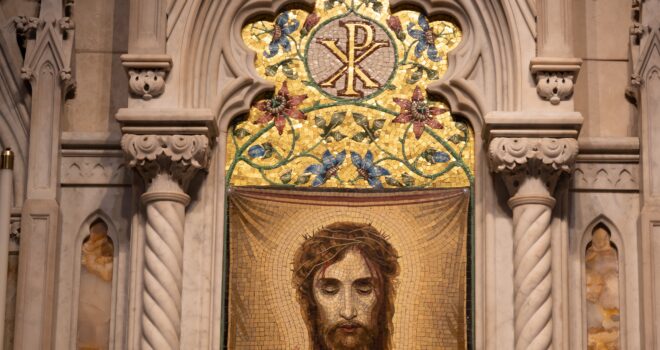

image: Christ Triumphant by Peter Paul Rubens/Wikimedia Commons