Given how the idea of “social justice” has been hijacked by activists clamoring to overturn societal norms, it will come as a surprise to learn that a beatified Catholic has written a thoroughly scriptural account of that term. After reading Blessed Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski’s Love & Social Justice: Reflections on Society, it will be impossible to forget that Christ and His Church are the true source and defenders of social justice. In short, this is an indispensable handbook for recovering an authentic Catholic understanding of society and how to make it better in Christ.

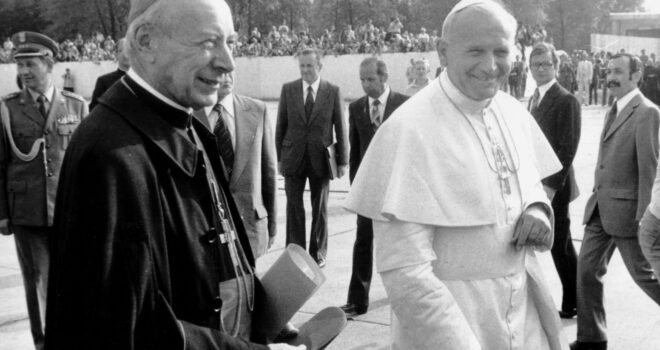

Blessed Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski (1901-1981) was a towering figure in Polish Catholicism and an influence on Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II). Hopefully Arouca Press’s publication of this book will make him better known outside Poland. During his lifetime Wyszynski witnessed the downfall of the Russian and German empires after WWI, followed by the institution of an independent Poland. Twenty years later saw its conquest by the Third Reich, and then post-WWII Soviet domination behind the Iron Curtain. But nourished by a robust Catholicism and the shining example—even in temporary defeat—of heroic Polish history, Wyszynski fleshed out the social teaching found in Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum and Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno, as well as other magisterial teaching. He did that by analyzing the situation in Europe and, significantly, by pointing again and again to the teaching on human relations as directed by God in Sacred Scripture.

Wyszynski starts with God and the person—in other words, traditional Catholic anthropology—before proceeding to family and nation (ethnos). Only then does he fully consider the state and its roles. He denounces communism, socialism, and other forms of materialist totalitarianism, but he does not spare capitalism in its corrosive aspects either. This exposition of social justice is much more compatible with distributism and integralism than modern liberalism. Love & Social Justice (LASJ) promotes the building of the nation-state instead of finding ways to divide people. It depends on love and gratitude, not hatred and resentment.

Wyszynski’s book is divided into four volumes with further divisions within each volume. Volume I concerns “Man and Family in Social Life”; Volume II is about “The Nation, State, and Church”; Volume III delves into “The Social Crusade”; and Volume IV examines “The Labor System and Property.” The Cardinal wrote this book during WWII while Poland was occupied by German forces. For that reason and its frequent use of older industrial examples for its argument, some might think this book outdated, but that would be a mistake. It is true technology has expanded since his time, but that takes nothing away from his arguments. Indeed, it endorses them because technology has exacerbated modernity’s assault on the essential components of a Godly society, helping to separate person from person, members of families from one another, and fellow citizens from working for the common good.

This is a daunting book in size (554 pages), but that should not dissuade potential readers. Chapters are mostly short and are well-organized. LASJ could be read in small increments, and even dipped into at leisure. Conceivably, given the tremendous amount of scripture passages, one could use the book as the basis for meditation, even lectio divina. This powerful and prophetic book will also surely spur many to read papal encyclicals on Catholic Social Teaching.

There are far too many examples and quotes to use for an essay of this length, so only a few will have to suffice. The book begins with Exsurgat Deus: “Arise, O Lord, and let Thy enemies be scattered; and let them that hate thee flee before thee” from the Book of Numbers. It ends with this passage: “Naboth’s vineyard must be taken back from the hands of King Ahab. [N.B.: this is not a call for a leftist-style revolution as in some pseudo-Catholic social justice, but rather a re-ordering of values and restoration of Godly justice.] The authority of the state sovereign over private property is limited by God’s law, the rights of the owner, and the rights of society.”

Again and again we receive faith-filled nuggets such as this: “It is in vain that nations look for wonderful, life-giving, and eternal wisdom outside of God’s laws” (35). Timely? Absolutely! Or: “Only religion knows who man truly is, but the world, which has liberated itself from religion, prefers to wander in the darkness than to return to the Christian response” (50). That is because “technology has become man’s new god” (51).

Wyszynski lays out what a successful nation-state must do. It must respect and nourish family life, and it must not usurp the Church’s role. Secular government must ensure the common good, while the Church strives for the salvation of all souls under its care. “Only when both [Church and state] act together do they allow man to achieve the right goal, the perfection of life” (63).

Contrary to ideas coming from both the secular and Church world today, LASJ envisions a world of expanding population as being the most obedient response to God’s wishes. “Experience shows that bringing up children in a tough and strict way is easier in a large family, as having only children leads to the upbringing of selfish youths who recline in their family nest, which has been prepared by Providence for their non-existing brothers and sisters” (78). Furthermore, “it is not overpopulation but rather an unjust division of goods of the earth and an unjust socio-economic system that are the cause of humanity’s misery” (84). Wyszynski spends the remainder of the book painstakingly showing what an authentically Catholic social justice looks like and how neither capitalism nor socialism and communism can implement the justice desired by God.

The common definition of justice involves punishment and possibly revenge. The Catholic understanding of justice means giving a person what s/he is due. Thus, the application of the principles in LASJ does not entail an arbitrary division of goods, but instead ensuring that every family has what it needs. This enactment of social justice is motivated by and carried out with love. The result is a living out of Christ’s Gospel. This runs contrary to the current preoccupation with ruthlessly criticizing and even despising the land and people of one’s patrimony. As Wyszynski puts it, “We all know how difficult it is for egotists to be good sons and daughters of their nation: they would prefer to see the death of their own nation than to make even the smallest sacrifice for it” (154). What a painful diagnosis, but how true, especially in our own era.

There is not enough space to go into more contents of LASJ: socialization, cooperation, corruption, farming, worker safety, the importance of private property, the responsibility of the rich, etc. Some today will say that our civilization—created from and nourished and sustained by the Christian Faith—is coming to end. They may be right. However, if any nation-state can be salvaged, then surely Blessed Cardinal Stephan Wyszynski’s Love & Social Justice gives us a blueprint of how to do it.