If you’ve been paying attention to pop culture, you have probably noticed that contemporary society has developed an intense, almost obsessive interest in racial and ethnic identity across artistic media. Issues of representation have taken center stage in the world of art and entertainment. It is not surprising that this preoccupation has also extended to the question of how our Lord Jesus Christ is portrayed in devotional art.

People today tend to critique traditional imagery of Jesus for not being historically accurate. Jesus, after all, was not a white man with blue eyes and sandy blond hair; He was Levantine Jew whose physical resemblance was likely more akin to today’s Syrians, Lebanese, and Israelis. If we saw Him on the street today, we might mistake Him for an Arab or a Berber.

But if we know that Christ was not Caucasian, why is He habitually depicted as such? The predictable go-to answer is white supremacy: It is said that depictions of a white Jesus reflect an outmoded Eurocentric view of Christianity, “whitewashing” Christ so as to remove Him from His Semitic context and reimagine Him as a white man. The implication is that Jesus’s true ethnic identity is being suppressed as an expression of religious white-fragility.

It is par for the course that moderns cannot put down their racial lens, even when considering our Lord and Savior. Even so, the contemporary perspective is sadly shortsighted, as the truth is considerably more nuanced. The reason we see Jesus depicted as Caucasian has less to do with white supremacy and more to do with theology. We must remember that, before a few decades ago, nobody really cared about Jesus’s ethnicity. Christ’s identity as the incarnate Word of God was vastly more important than what color His skin was. Traditional Christian theology considers Jesus as God become flesh, incarnated for the sake of human salvation. In other words, what Jesus does as Redeemer is of infinitely greater import than His ethnicity according to the flesh. His mission is universal.

The universal nature of His mission historically enabled every culture to see Christ according to their own unique cultural imagery—including race. Since Christ came for all men, people naturally depicted His physical characteristics after their own image and likeness. Since we in the West happen to live in a society grounded in European culture, we have viewed Christ as European. But if we were to travel to other cultures, we would see the opposite—Christ would be depicted according to each respective culture’s ethnic norms. In China, Christ is Chinese; in Ethiopia, Jesus is black, and so on. His racial identity was almost incidental, subsumed beneath the much weightier focus on His theological identity as the Word of God made flesh.

If contemporary society focuses more on Jesus’s skin color, it is because it has lost sight of the theological truth of who Jesus is. Moderns do not consider Jesus as the incarnate Son of God, “God from God, light from light, true God from true God.” Pop culture considers Him little more than an ethical teacher. Having forgotten Christ as Lord, it can only see Him through the reductive lens of ethnic identity, the same lens through which everything else is viewed.

But do not take my word for it. Let us take a brief survey of historical images of Jesus from around the world so we can see how Europeans were not alone in envisioning Jesus after their own kind.

We shall begin with the Romans, the cultural milieu Christianity was born into. The Christians of ancient Rome viewed Jesus according to their own cultural norms—as a Caucasian, beardless youth. In Greco-Roman society, the image of the beardless youth was equated with divine vitality. A fantastic example of this beardless-Christ is the image of Christ the Good Shepherd from the Catacombs of Domitilla in Rome:

Not only dis Christ depicted as a Caucasian, beardless youth, but He is also garbed in the apparel of a Roman rustic, such as a 2nd century Italian shepherd might have worn.

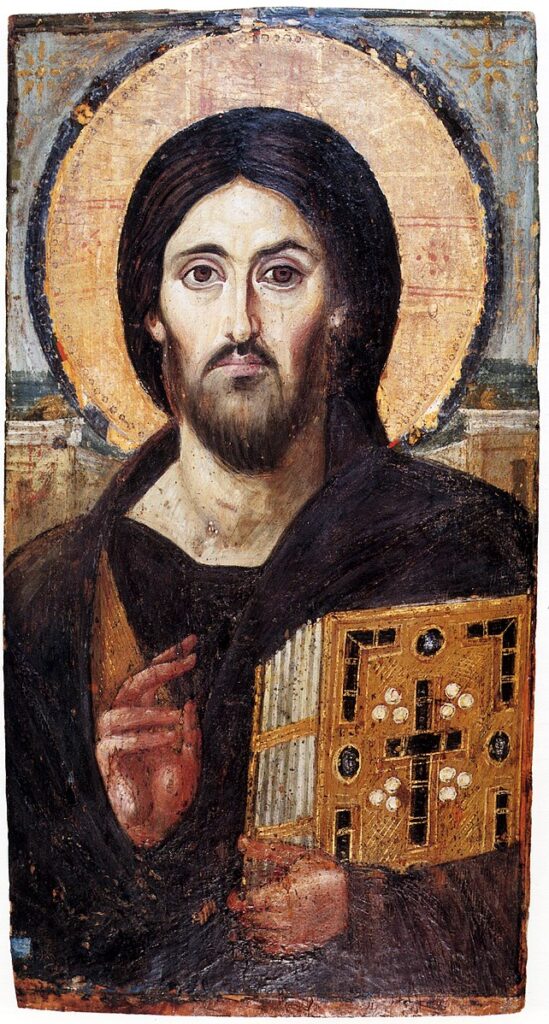

If we look at early images of Christ from the Levant, we see he has a more distinctive Semitic appearance. The famous 6th century image of Christ Pantocrator from the St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai shows an olive-skinned Christ with bushy hair and a thick beard:

While the St. Catherine’s image more closely approximates to the popular image of Christ, we should not fail to notice His distinctively Middle Eastern garb (the black cloak or coulla of the Egyptian monk) and the Gospel book, the decorations of which could be found on any liturgical book of the Gospels used in a major Eastern church to this day.

A Syrian image of Christ from the same era found in mosaic in the church of Diyarbakir (modern day Turkey) shows a uniquely Syrian-looking Christ—he is tall and lanky, dark-skinned with a shock of curly black hair and side whiskers crawling down his face. His eyes are big and brown, looking out at the viewer as he gestures to an open copy of the Gospels:

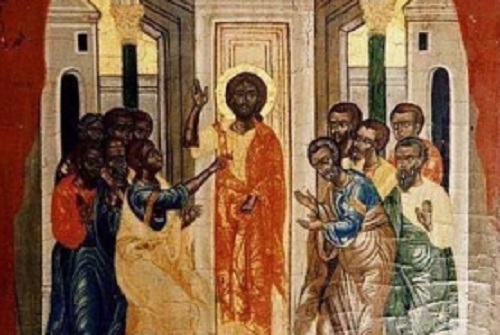

The Armenians viewed Jesus as a traditional Armenian-father figure. Classic examples are found in the 14th century Glajor Gospel. Consider this image of the Transfiguration:

Here we see Christ is short haired and stocky with a fulsome beard and thick lips. His woolly eyebrows shield his dark eyes, beneath which are thick eye bags. The Christ of the Glajor Gospel is so Armenian looking he could be the owner of your local Armenian diner.

Heading across western Europe to the Scottish isle of Iona, we see a strikingly different depiction of our Lord: images of Christ in the 9th century Book of Kells bear a distinctively Gaelic look:

With unkempt locks of curly red hair and bright green eyes, the Christ of the Book of Kells is a quintessential Irishman, reflecting the Irish cultural background of the Ionan who decorated this fabulous manuscript.

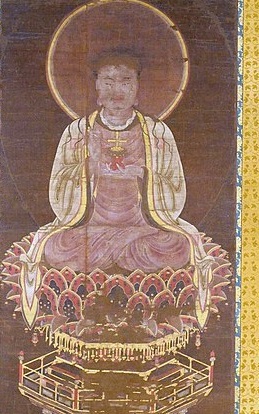

Asian images of Christ, meanwhile, bear distinctively Asian characteristics. Observe this portrait of Christ as an Indian sage from the 9th century Magao paintings, found in China’s Gansu province:

Another Chinese image from the 12th century—associated with the Manichaean sects—portrays Jesus in the garb and posture of a Buddhist holy man, sitting atop a pagoda in the double-lotus position:

A more ethnically Chinese Jesus can be found on a 10th century banner from the west Chinese Uighur kingdom of Qocho:

The Qocho image is interesting as it shows not only an ethnically Chinese Christ but depicts him in the context of an East Asian court, flanked by attendants in ceremonial dress. This scene would have been recognizable in the court of any Chinese sovereign.

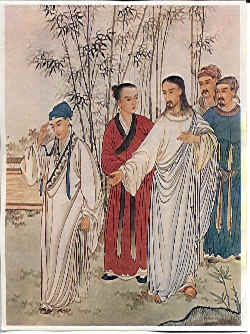

It became standard among the Chinese to show Christ as a Chinese sage and his disciples as Chinese students. This convention has remained consistent over the centuries. Consider this 19th century Chinese image of Jesus Christ and the rich young man:

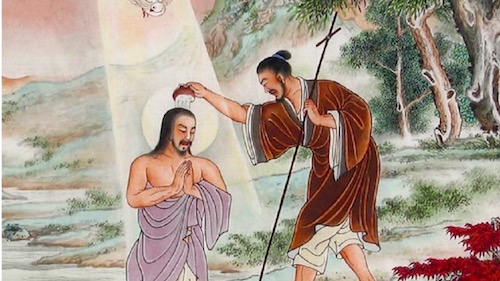

Contrast this with a more modern image of the baptism of Jesus shown in the newspaper South China Morning Post from the early 20th century; we see both Christ and John the Baptist depicted as traditional Chinese men:

The Philippines is the only Catholic country in East Asia. The most popular image of Christ among Filipinos is undoubtedly the Santo Niño, an image of the Child Jesus enshrined in the Visayan island of Cebu, the center of Filipino Catholicism. Though not an indigenous image (the Santo Niño was reputedly brought by the Spaniards in the 16th century), this Jesus is clearly non-white:

Incidentally, the most popular image of the Blessed Virgin in the Philippines is that of Our Lady of La Naval, which was carved by a Chinese craftsman and depicts Mary with Asian features. Another example of this is the image of Our Lady of La Vang from Vietnam, which offers us a splendid Vietnamese Mary holding the Christ child; both are dressed in the traditional Vietnamese ao dai garb:

Black images of Christ were common in Africa. An 18th century Ethiopian image shows Christ as an African man with short hair:

An image from the Copts of Egypt around the same time shows Jesus and His disciples as all dark skinned, some Semitic and some clearly black, probably Sudanese:

Crossing over to the Americas, the oldest image of Christ produced in here was created in 1539 by Aztec converts as a gift to the Franciscans of Mexico City. This image (now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York) depicts Christ appearing in a Eucharistic miracle during the Mass. Though situated during the Mass, the image is full of Aztec iconography and feather art. Christ—who appears ethnically ambiguous—is flanked by a Spaniard on his left and a Native American to his right:

The use of indigenous iconography to depict Christian figures is not unique to this image. The famous 16th century picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe (according to tradition, a miraculous image produced on the tilma of St. Juan Diego in 1531) shows the Blessed Virgin Mary as a native woman dressed in the traditional Aztec raiment of an expectant mother:

In this brief survey of Christological images from around the world, we can clearly see that Jesus Christ has been depicted in many ways. He has been a Chinaman, an Armenian, a Copt, a black African, a Filipino, and every other ethnicity under the sun. This tendency to appropriate Christ to one’s own ethnic group is a constant theme in global Christianity.

This leads us to several conclusions:

First, it is not wrong for cultures of European descent to depict Christ with European features. As we’ve seen, Christians have always viewed Christ as one of their own, whether European, Asian, Native American, or any one earth’s varied peoples. It is perfectly expected that European-based imagine Jesus as a white man.

Second, there has never been any conspiracy to hide or suppress non-white images of Christ. Far from it—wherever it has spread, the Church has encouraged and nurtured images of Jesus Christ according to local culture ethnicity.

Finally, the diversity Christ’s depictions remind us that the racial identity of Jesus is not of ultimate importance. Christ came as the savior of all mankind; the wonderful assortment of ethnic depictions of the Lord reflect the universality of the Church, which is composed “of a great multitude…from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and tongues” (Rev. 7:9).

All images are in the public domain.