In this ninth posting, we are continuing the blog series with content from biblical scholar Scot McKnight. McKnight has recently published New Testament Everyday Bible Study series with HarperChristian Resources. McKnight combines interpretive insights with pastoral wisdom for all the books of the New Testament. Each volume provides original meaning, fresh interpretation, and practical application.

In this blog series, we’ll be sharing Scot’s insights and wisdom on the book of Philippians. It is available as a book as well: Philippians and 1 & 2 Thessalonians: Kingdom Living in Today’s World.

For twelve weeks, Bible Gateway will publish a chapter from the Bible study book, taking you through the full text of McKnight’s study on Philippians. For this week, here is the ninth study, A Common Life of Co-Workers | Philippians 3:1b-11

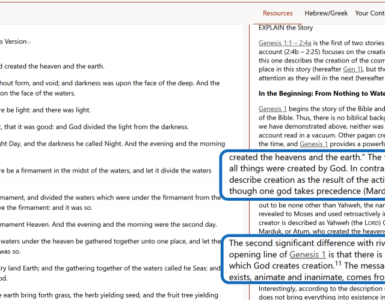

1 It is no trouble for me to write the same things to you again, and it is a safeguard for you. 2 Watch out for those dogs, those evildoers, those mutilators of the flesh. 3 For it is we who are the circumcision, we who serve God by his Spirit, who boast in Christ Jesus, and who put no confidence in the flesh—4 though I myself have reasons for such confidence.

If someone else thinks they have reasons to put confidence in the flesh, I have more: 5 circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews; in regard to the law, a Pharisee; 6 as for zeal, persecuting the church; as for righteousness based on the law, faultless.

7 But whatever were gains to me I now consider loss for the sake of Christ. 8 What is more, I consider everything a loss be- cause of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whose sake I have lost all things. I consider them garbage, that I may gain Christ 9 and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which is through faith in Christ—the righteousness that comes from God on the basis of faith. 10 I want to know Christ—yes, to know the power of his resurrection and participation in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, 11 and so, somehow, attaining to the resurrection from the dead.

No one has stronger criticisms of one’s former life than a convert. Some talk about how bad of a sinner they were or how deep they were into drugs or money or alcohol or sexual escapades. Some talk about their former religion the way divorced people at times describe their ex.

In my lifetime I’ve heard nothing less than vituperations and accusations for one’s former Roman Catholic or Methodist or Presbyterian or just plain “liberal” church: “I was raised in that church and never once heard the gospel.” As one who has done research in conversion stories, I’ve heard that tale more times than I can count. Nasty rhetoric about one’s former life seems irresistible.

And always has been. Paul himself is such a person. He describes his past in a way that permits him to criticize his present opponents. That is, his past is where his opponents are now.

A Strong Accusation

The language ancients used for their opponents does not play well today. In fact, that kind of strong language, often calling one’s enemy some animal, was only part of the prophetic toolbox. John the Baptist was harsh, Jesus was harsh, Peter was harsh, Revelation ramps up harshness, and Paul was harsh too. (If you really want to read harsh accusations against one’s opponents, read what Luther and Calvin say about the Catholics and Anabaptists. Yikes.)

I’m not excusing anyone, and I don’t think we should talk like this about one another, but I do want us to see the harsh accusations of Paul in their context. What was said in their world may not be license to say the same in our world.

Paul opens chapter three with a line that quickly erupts with explosive clarity. He starts with, “It is no trouble for me” (3:1), which could be translated, “I have no hesitation” to write to you about these things. This rather sedate statement suddenly shifts in tone to, “Watch out for those dogs!” Then he adds “those evildoers, those mutilators of the flesh” (3:2).

To call someone “dog,” which is still an insult in Germany, is an insult. That insult is unfolded into two categories, one moral (“evildoers”) and the other about law observance (“mutilators of the flesh” refers to circumcising gentiles). Which makes it clear that some opponents of Paul in Philippi were law-observant Jewish Christians.

Here’s another problem. Christians have easily slid from Jesus’ exaggerated rhetoric about Pharisees to thinking all Jews are Pharisees. Then they mix into the bowl of group denunciations Paul’s exaggerated rhetoric about “dogs.” Then they drop the exaggerated talk of opponents to think all ordinary Jews are worthy of such condemnations and before long we have outright prejudice and racial hatred, the kind that saw Jews as Christ-killers. Then we have the Holocaust. This is the danger of exaggerated rhetoric, and it must be made clear right here. Be careful. Our world is not their world. These words don’t work in our world.

What also must be emphasized, and this kicks the stool out from under many, is that Paul is not here opposing Jews per se nor is his beef with Judaism. Paul’s heated rhetoric aims at Christians who think gentiles or all believers must observe the law. Those Christians were probably Jewish Christians, but it’s not the Jewish part that concerns him.

One does not find here, then, an argument with another religion. Rather, Paul perceives a dangerous departure from the true gospel about Jesus Christ by Christians bent on being as zealous as Paul was in his former life about observing the law of Moses.

A Strong Claim

Paul makes strong claims about his past so he can crush the claims of his opponents. He crushes them so he can magnify the gospel about Jesus Christ. Those are the two moves he makes in this passage.

Paul turns his past completely upside down when he says “we,” not they, are the “circumcision.” That is, the true circumcision is not fleshly removal of skin but serving “God by his Spirit” and those who “boast in Christ Jesus” and those “who put no confidence in the flesh” (3:3).

These are all jabs at his Jewish Christian opponents who believe Paul has denied the law and cut into the core identity of Israel/Jews. (One reading of Galatians 3:19–29 reveals how Paul thinks about the topic.) Their “confidence in the flesh” is an appeal to their circumcision and, at the same time, a very strong criticism by Paul. For him, “flesh” is corrupted human flesh that rejects the Spirit and Jesus as their own Messiah.

But Paul decides to play their game of flesh confidence. He’s a Jew of the Jews, Israelite of the Israelites, Hebrew of the Hebrews. When it comes to his style of Judaism, that is, which approach to law observance he embodies, he’s a Pharisee. This meant someone who interpreted the law carefully by expanding it to spell things out more clearly, and thus someone who followed it scrupulously and strictly. Like Catholics, evangelicals, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists adhering to their very special group-taught traditions today.

So committed had Paul been to law observance that he persecuted the church. He tops these strong claims off with the strongest of all claims. He puts forward the standard of standards, “righteousness.” A righteous person–like Joseph (Matthew 1:19)–is one who consistently follows the law. By Pharisee standards, Paul says he was “faultless,” and Bockmuehl says it well: many “cringe at this claim” by Paul.

Jews believed they could follow God’s law; they believed failures were atoned for on the Day of Atonement. Sacrifices meant they were clean with respect to law observance. Those who lived like this were “faultless.” This does not mean sinless. Paul had been a faultless sinner! These strong claims are not exaggerations, and neither are they claims to perfection. Have you ever heard someone say they are a devout Catholic or an observant Jew? That’s the kind of claim Paul was making about his past.

His various claims were also boundary markers between Jews and gentiles that became symbols of one’s radical commitment to Israel’s God and to God’s law. They function then as public statements of one’s allegiance. Much the way daily devotions, or weekly church attendance, or serving in a homeless shelter do in our world. Such practices identify us and mark us off from others who don’t do such things.

So Paul’s boundary-marking claims are strong: he was initiated into the covenant by law observant parents; he’s from the innermost tribes (Judah, Benjamin); he can speak and read Hebrew; he’s a Pharisee; his zeal has no limits; and when it gets right down to it, he was a totally observant Pharisee.

There is no duplicity here. Paul was not a man crushed by a guilty conscience. Paul was not worried about going to heaven when he died. He was not in fear of losing his salvation. That man had a robust confidence in his God, in the law, and in his faithfulness to it. No, he didn’t convert to Christ to assuage guilt. He converted because he met Jesus. That encounter shattered his old way of life.

Think about it this way: he magnified his Jewishness; he boasted about his faithfulness. Not as personal bragging but so he can speak to his law-observant opponents, best them, and then say, “In spite of all my zeal, I was wrong. I did not know that the church’s gospel was right. Jesus met me, and I now know that he is the Messiah. That means my former zeal was misguided.” Which then implies, “So is yours. So is theirs.”

A Strong Confession

His former way of life was shattered by an entirely new perspective: what were “gains” are now a “loss” (3:7–8). The term will reverberate among some of his opponents all the way back to Jerusalem. A term that will be heard in synagogues all over the Mediterranean is that Paul considers his former law-observant life as “garbage.” The Greek term is skubala. Some wonder here if this might be a momentary cuss word for Paul, something like “crap” or its more vulgar alternative that rhymes with “skit.” The term, however, is best translated as feces. Skubala was used in medical manuals for excrement tossed into the garbage. So his former life was trashed.

What matters now is “knowing Christ Jesus my Lord” (3:8). The person-centeredness of this expression cannot be missed. His faith is in a real person, the man from Galilee who walked its hills and taught in parables and opened doors to the table fellowship inside some had never imagined possible. Who made astounding claims for him- self and worked wonders and miracles and healed people outside and inside homes. Who entered Jerusalem in protest, was crucified, was buried, and was raised and then ascended to the right hand of the Father.

The gospel is about Jesus the person, not just what he accomplished. The gospel is not a set of ideas but a living, breathing incarnation of God. He is the One Paul now knows, and knowing Jesus has transformed his life.

On this side of his conversion, he is “in him,” and that means his righteousness is not Pharisee-based law observance but the righteousness that comes “through faith in Christ . . . that comes from God on the basis of faith” (3:9). We hear a new echo of “not by works of the law but by faith,” a very common expression on Paul’s lips in the days of writing Galatians and Romans. He wants to “know Christ” in his fullness. Paul wants to know “the power of his resurrection” and that means he wants to know–think about this slowly–“participation in his sufferings” so he can, like Jesus, be “like him in his death.” Because the death of Jesus–remember the U-shaped theology of 2:6–11–led to his exaltation, so Paul knows if he participates in his death he will also participate in his resurrection and be raised from among the dead.

Paul’s writing leaps and bounds and shifts and turns and returns. So readers have to grip his letters tightly and hang on for all those moves. We started with his calling his opponents “dogs,” and we find him on the near side of his former life where he is so in tune with Jesus he wants the pattern of Jesus’ life to shape his own life. He’s ready to die because the One who has died is the One who was raised. His confidence in the flesh never attained the kind of confidence he now finds in Jesus.

Questions for Reflection and Application

- How does Paul use his strong rhetoric about his former life to denounce his opponents? What is hi linguistic and confessional strategy here?

- Who is Paul criticizing and opposing in this passage?

- How has Christian rhetoric been used to move beyond Paul’s intent here into demonizing Jews?

- What “group-taught traditions” or “boundary markers” do you notice in your own denomination of Christianity?

- What is your conversion tale? How did you come to follow Jesus? Have you told your story in the past, and how has this lesson impacted how you might tell that story in the future?

The New Testament Everyday Bible Study is published by HarperCollins Resources, a division of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc., the parent company of Bible Gateway.

The post Why Confession is Imperative for Our Common Life in Philippians 3:1b-11 appeared first on Bible Gateway Blog.