Christianity burst upon the pagan world with an astounding message— God wanted a personal relationship with every man and woman in creation. Friendship with Christ conferred dignity on all humanity— slaves, women, the sick, and the disabled—a fact that was reflected in the art Christians had produced in the catacombs and in early churches.

Protestant Reformers claimed that the personal nature of the relationship with the Lord had been usurped by intermediaries, particularly the clergy, but also the saints. Catholics, on the other hand, understood that holy men and women, whether martyrs or confessors, had enjoyed a special friendship with Christ, one that not only instructed, but also inspired, and that all disciples of Jesus belonged to one body, sharing in each other’s gifts.

Caravaggio’s Vision of Conversion

The first and most essential step for this friendship to bloom was conversion. To turn away from the distractions of this world, to favor a relationship with Christ over any other, to conform one’s life to Jesus seemed overwhelming, especially in the age of post-Reformation uncertainty. How to make that first fearful step of following Christ attractive or, better yet, captivating?

Ask Caravaggio.

After a decade of painting still lifes in the shadows of Rome, Caravaggio got his big break in 1599, when he was commissioned to paint two canvasses of the life of St. Matthew for the French church of St. Louis in Rome. The stakes were high. The king of France, Henry IV, had just reverted to Catholicism the year before, and the church was charged with preaching conversion Masses to pilgrims during the year 1600. Furthermore, Caravaggio did not work in fresco, the preferred medium for mural painting, but would be working in the less prestigious oil on canvas.

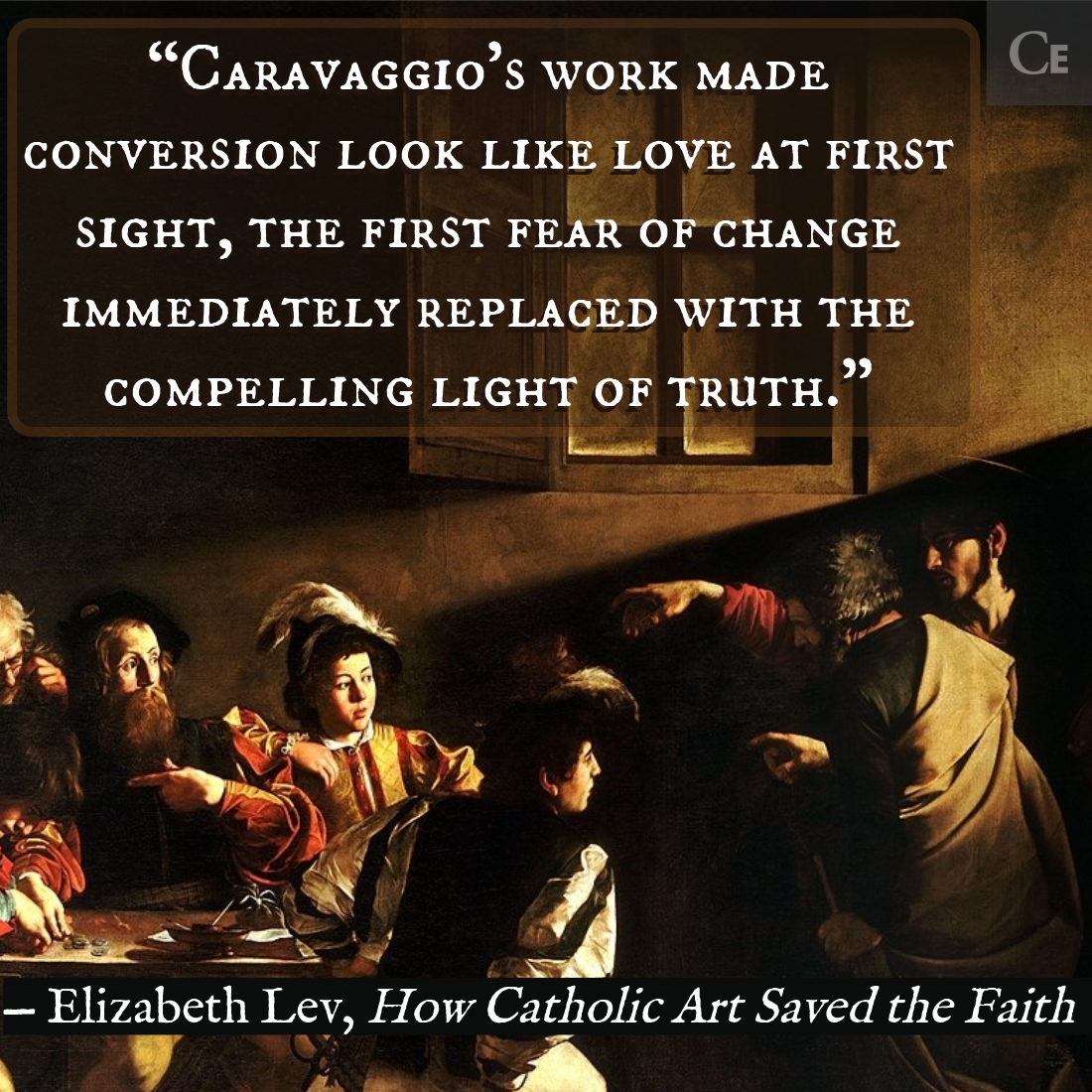

Caravaggio played to his strengths in the commission, producing one of the most compelling scenes of conversion in the history of art. In The Calling of St. Matthew the wealthy tax collector sits at a table with his colleagues, counting the day’s take.

Surprisingly, they do not wear the drapes and robes familiar to biblical painting, but instead don contemporary dress. Caravaggio employed his still-life skills to render shimmering silk, lush velvet, and luxurious brocade. A slim rapier rests in one man’s scabbard. These men appear to have all that one might desire: money, status, comfort.

The scene is interrupted by two men dressed in simple woolen robes, more consonant with the iconography of New Testament scenes. They are barefoot, and the younger of the two, Jesus, turns toward the table and points with a finger reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Adam in the Sistine Chapel’s Creation of Man.

“Follow me,” Jesus tells him (Matt. 9:9). The effect of these words hits several of the men like a lightning bolt. One young man jolts upward; the other youth seems to bask in the vision.

Matthew however, recoils in shock. His finger turns toward himself as if to ask, “Who, me?” At first glance, Matthew does not appear eager to leave his belongings, his life, yet Caravaggio unveiled a new technique that reveals the rest of the story—light.

The powerful beam of light that projects from behind Jesus’ head, the space of the altar in the chapel, hits St. Matthew full in the face. It is supernatural, since the window behind his head gives off no light. This light, the clarity of vision in which Matthew sees Jesus, the Way and the Truth, before him, is like an actor in the story, actively drawing the saint to his conversion and his vocation. Caravaggio later added the second figure, St. Peter, a little reminder of the importance of the Magisterium in connecting men to Christ.

Although it is never suggested by contemporaries, the modern age has begun to eschew the traditional identification of St. Matthew, preferring to see him in the boy with the bent head at the far end of the table. None of Caravaggio’s peers or critics proposed such an idea, and it doesn’t stand up to any kind of art historical methodology, yet this interpretation has gained momentum, seemingly even from Pope Francis himself.

This alternate explanation neatly illustrates the difference between the modern age and that of the Catholic Restoration. The young man favored by twenty-first-century critics is absorbed in the here and now of counting the money before him. The light rests upon his head as if gently tapping him to look away from worldly pleasures. In this interpretation, Jesus would be standing before the supposed Matthew, patiently waiting for the boy to finish his business and decide to join Him.

While this idea of the Lord waiting on sinners to complete their affairs before conversion is appealing, especially to an era like the present, the Catholic reform did not see conversion this way.

In the preceding chapter in Matthew, Jesus stressed the urgency of conversion when he told a young man who hesitated at His calling, “Follow me, and leave the dead to bury their own dead” (Matt. 8:22). Looking closely at Jesus’ feet, the viewer can see that Christ is in motion; in a moment He will have already passed by, along with the personal invitation to conversion.

Immediacy was the modus operandi of Caravaggio, as it was the mantra of the post-Reformation era. The pilgrims who walked the long way to see this work were already disposed in their hearts to find Christ should He walk by, just as Matthew had looked up from the table, searching for something more, just as Jesus walked by.

Caravaggio’s work made conversion look like love at first sight, the first fear of change immediately replaced with the compelling light of truth.

✠

This article is adapted from a chapter in Elizabeth Lev’s How Catholic Art Saved the Faith: The Triumph of Beauty and Truth in Counter-Reformation Art, available from Sophia Institute Press.

We also recommend K.V. Turley’s interview with Elizabeth Lev, “Sacred Art is the Triumph of Beauty and Truth.”

image: Caravaggio’s masterpiece in San Luigi dei Francesi via Isogood_patrick / Shutterstock.com