“O Come, O Come, Emmanuel” is a beautiful hymn that we hear frequently throughout Advent. It has seven verses, each of which come from one of the O Antiphons. These are seven antiphonal prayers specifically used during the Church’s evening prayer from December 17 to 23, leading up to the Nativity of Our Lord. The O Antiphons look back through the history of salvation presented in Sacred Scripture, and they cry out for the long-expected Messiah who is the culmination of that history. Praying with these titles and antiphons has the potential to make Advent deeply memorable. Every time we hear these words and images, or sing the hymn, our expectation of God-with-us is kindled. This series of reflections is offered in hopes that individuals and families will be ready to pray the O Antiphons in the final week before Christmas eve; that they will be able to savor the birth of Emmanuel in that Bethlehem stable.

O Key of David, opening the gates of God’s eternal Kingdom: come and free the prisoners of darkness!

On December 20, we pray with the images of keys and gates, pondering their functions. Keys lock and unlock doors and gates. Gates serve as barriers and thresholds, delineating one area from another. Keys and gates together provide access to, or exit from, defined and enclosed areas.

As with most mundane material realities, keys and gates also serve as analogies for parts of the spiritual life. In the Sacred Scriptures, keys serve as symbols of authority, often handed to ministers who are charged as stewards of that authority. Once granted the keys, stewards then can access areas that only the original key-giver had (a landowner or a king, for example). For their part, gates represent spiritual passages, moving from one state of life to another.

One episode in the Old Testament clearly illustrates the symbolism of keys. Isaiah prophesied to the King of Judah about Eliakim, the chief steward: “I will clothe him with your robe, and will bind your sash on him, and will commit your authority to his hand. … And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David. He shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open” (Is. 22:21-22). The keys represent the fact that this prime minister has full access and complete authority over the kingdom.

Gates are also prominent in the Old Testament. They are used to mark off sections of the Tent of Meeting in Exodus. They are used to fortify he Temple when it is constructed in Jerusalem. They are iconic of the stables in which horses and chariots are held. They are the points from which marauders set out to capture a city or a person. They are also the places at which some men meet their wives. Each of these clearly point us forward to deeper spiritual realities.

Both symbolic images occupy a central position in one memorable Gospel episode. During His public ministry, Jesus goes into Caesarea Philippi and passes “the keys of the kingdom of heaven,” along with authority to bind and loose, to His own chief steward, Simon. In that moment of handing on those keys, Jesus changes Simon’s name to Peter. Then, the Lord promises that the gates of hell will not prevail against the Church built on His authority, the authority passed to Peter. Jesus has clearly passed on His authority to another to lead an assault against the gates of hell, the structures that would harbor evil and unleash it on the world.

That leads us to the request of this antiphon. The authority and power that Jesus has passed to Peter and the Church has not been altogether successful, and so there is evil and darkness in the world. Evil and darkness are so prevalent that many people, including each of us, are under the power of darkness. And, so, we need liberation.

Of course, Jesus is the Person to whom these images point. In his first synagogue lesson at Nazareth, Jesus unrolls the scroll of the prophet Isaiah and proclaims that He has been sent “to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound…” (Lk. 4:16-21; Is. 61:1-2). But, those prisoners, the antiphon tells us, are “prisoner of darkness.” Therefore, Jesus does not simply identify himself as the Key that sets prisoners free, but also as the Light of the World (Jn. 8:12). Ultimately, we are brought to a deeper understanding of the ways that Jesus intends to liberate us from the darkness of sin.

A well-known painting, William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World, draws all these themes together. The painting depicts Jesus, coming out of a dark forest and carrying a lamp that provides the only light in the scene. Jesus knocks at a door, which has the same function as a gate. The most important detail, though, is that there is no doorknob on Jesus’ side of the door. Although He is the Key that sets prisoners free, the prisoner on the inside must choose to allow the Key to enter and do His work of liberation.

As we pray with this antiphon on December 20, we might sit and ponder these questions: Do I recognize Jesus as the Key who sets me free? Are there practical habits that need to come along with the gift of liberation by Jesus, which will help me experience freedom? Do I stand in awe at the gates of God’s eternal kingdom? Do I ask for full access to that Kingdom?

**This translation of the O Antiphons is taken from the translation available on the website of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops: https://www.usccb.org/prayers/o-antiphons-advent.

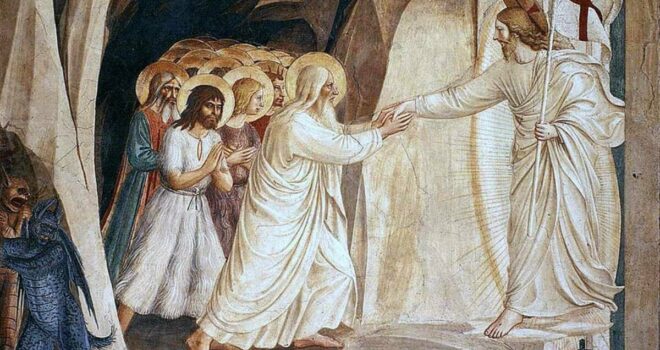

Image: Fra Angelico, Harrowing of Hell