On Christmas Day of 800, in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Charlemagne (742-814), King of the Franks, was crowned as Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III (750-816), reviving a title that had disappeared from the Western half of the Mediterranean world since the deposition of Romulus Augustulus, in 476. Frankish knights, Italian clergy, and the people of Rome cheered as they witnessed the historic moment that marked the return to a beloved past.

But what exactly was the meaning of this coronation? And what kind of relationship between secular and religious spheres did it symbolize? Clearly, the issue mattered to Charlemagne, who later on refused to have his own son Louis crowned by the bishop of Rome. Instead, he crowned him himself, at the Frankish capital of Aachen (today a German town near the border with Belgium). His most important biographer, Einhard (c.770-840) later went as far as claiming that Charlemagne had not been aware of the Pope’s intention to crown him. Historians have determined that this story is not tenable. Then, why was Charlemagne displeased?

The problem was not the fact that the Pope had crowned him, but rather the interpretation given to this event by Leo and the papal court. In order to grasp this, we must first recall both the historical context, which is the rise of the Carolingian dynasty among the Franks, and the events leading up to the encounter between Charlemagne and Leo, which placed the Pope in a dangerously weak position.

The Franks were one of the Germanic nations that found themselves in control of certain territories after the disintegration of the Roman Empire in the West. For about 300 years, the kings of the Franks came from the Merovingians, a family whose deeds and misdeeds have been recounted by Gregory of Tours (538-594) in his Historia. Yet, over the course of the 7th century, Merovingian kings had progressively lost the ability to reward their followers with lands and offices, and by the 700s they were monarchs in name only. Effective power had been usurped by the family that would eventually be named Carolingians. Charles Martel, who defeated an invading Arab expedition at Poitiers in 732, was one of them. The issue faced by his son, Pepin (714-768), was that notwithstanding their unquestionable military and political skills, the Carolingians could not legitimately replace the Merovingians as kings. As explained by historians like Ian N. Wood, even at this stage the Merovingians were still seen as the legitimate heads of the Frankish nation.

While the Carolingians needed to fashion a new idea of kingship, in Italy the Pope had been struggling to keep at bay the Lombards, a Germanic nation that initially embraced the Arian heresy and that in the 6th century had invaded the Italian peninsula. Theoretically, the safety of Rome should have been guaranteed by the eastern Roman emperor; however, following the Islamic invasions, Constantinople was engaged in a struggle for survival and could not spare any reinforcements for Italy. The Lombards took advantage of the situation to enlarge their kingdom and isolate Rome. The Pope was thus surrounded by hostile, menacing forces that threatened both his safety and his independence.

At this point, an alliance between Church and Franks seemed the perfect solution: the Carolingians would acquire papal support, replace the Merovingians as kings, and forge a new idea of monarchy, legitimated by a genuine concern for justice and a conscious defense of the Christian people and the Catholic Church; while the Pope would obtain military support against the Lombards and begin a more thorough evangelization of the Franks. With the explicit blessing of Pope Zacharias (679-752), in 751 Pepin removed the last Merovingian king and took the throne; soon afterwards, he helped the Pope to repel the Lombard armies.

After the death of Pepin, his son Charlemagne further developed the idea of Christian kingship. In particular, he increased his authority in three ways. First, he conducted a series of successful military campaigns, crushing the Lombards, but also conquering the pagan Saxons and supporting the beginnings of the Reconquista in Northern Spain. Second, he favored the recovery of classical learning and an intellectual revival that is often called ‘Carolingian renaissance’, gathering at his palace scholars like Alcuin of York, and supporting the work of countless Benedictine monasteries. Thirdly, Charlemagne reimagined the role of the king as a sacred figure who had the duty to run the Church. This aspect of Charlemagne’s vision is the most significant if we want to understand the peculiar and dangerous situation in which Pope Leo found himself in 800. Because the Frankish king was envisioning nothing less than the reduction of the Church to a department of the state. Charlemagne did not intend to merely protect the Church, or favor it with subsidies and through the foundation of more monasteries. Rather, we find him busy calling councils, regulating monastic life, taking decisions concerning the liturgy, and even attempting to enforce morality by law. Not by chance, the great Catholic historian Christopher Dawson suggested that Charlemagne had started to act like a sort of Muslim cadi.

Pope Leo III was well aware of the situation, since in 796 he had received a letter from Charlemagne where the king had explained their relationship in these terms:

“Our task [i.e. Charlemagne’s] is, with the aid of divine piety, to defend the holy Church of Christ with arms against the attack of pagans and devastation by infidels from without, and to fortify it from within with knowledge of the Catholic faith. Your task is to lift up your hands to God, like Moses, so as to aid our troops.”

The state was about to absorb the Church, replicating the pattern of Caesaropapism observable in Constantinople, where the east Roman emperor was in charge of the church and often determined doctrinal matters.

Alarmingly, by 800 Pope Leo’s position had worsened. On the previous year, he had been ambushed by a group of conspirators who had wounded and imprisoned him. He was able to escape, but had to flee from Rome and reach Charlemagne at Paderborn, begging for support. This means that when Leo returned to Rome, accompanied by Charlemagne and his troops, the papacy truly risked being demoted to an imperial office. Is it possible then, that the interpretation that Leo and his court gave to the coronation represented a desperate yet genius move, the last resort to save the independence of the papacy and affirm the freedom of the Church?

If we look at the Liber Pontificalis, a document that represents the papal understanding of the events, the impression is that Charlemagne was not an emperor until the Pope crowned him. The text states that Charles was made (constitutus) emperor, receiving a sort of ordination from Leo. This account is subtly but crucially different from the one contained in the Royal Annals drafted at the Frankish court, which downplays the whole episode and blandly reports that Leo “put a crown on his [Charles’s] head.” Furthermore, as pointed out many decades ago by Robert Folz, Leo deliberately subverted the Byzantine imperial liturgy: while in Constantinople the patriarch crowned the emperor only after he had already been acclaimed by the army, the Senate, and the people, in Rome the Pope crowned Charlemagne before the acclamation. This may sound like a trivial matter to us, but in pre-modern societies physicality and public gestures were the visible signs of spiritual and political authority.

We can conclude that while Leo III returned to Rome in a weak position, after his reinstatement he took the initiative, reaffirming that the Bishop of Rome is the head of the Church, and carving a unique role for himself and his successors within the imperial framework revived by the Carolingians in the West. Leo’s actions and the fact that the papal interpretation of the coronation became the most widely accepted allowed the Church to maintain its independence. Of course, other attempts would later be made by secular rulers to control the Papacy, and we have to thank many other popes for safeguarding the Faith and the freedom of the Church. But Leo III’s inventive contribution in 800 was surely a stepping stone, which was recognized in 1673 when he was canonized by Clement X.

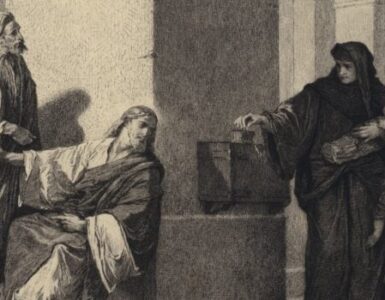

Image: Friedrich Kaulbach, The Crowning of Charlemagne via Wikimedia Commons