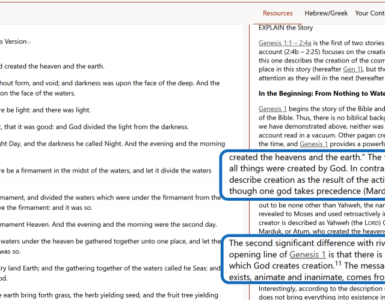

Let’s look at how the Greek word for humility was used in Paul’s setting. One of the prominent Greek words we translate as “humble” (tapeinophrosynē) could also be translated as “self-abasement” or “lowliness.” In Greek, there are words that are related to each other that convey the concept of humility, and this type of thing is referred to as “word groups.” Markus Barth, a renowned Swiss New Testament scholar that lived during the second half of the 1900s, shared this insight about the humility word group: “The entire word group which belongs with tapeinophrosynē, according to its usage in common Greek, is used in a negative sense and means a low slavish orientation.”[1]

This means the concept of humility would have been something totally shameful.[2] The culture was highly competitive and focused on self-exaltation (sounds familiar, doesn’t it?). So anyone who had a low social status, who was weak or lowly, was considered “humble,” and it almost always had a negative connotation.[3]

The early church father Augustine went so far as to say humility was an unknown virtue in the ancient world.[4] Given this cultural climate, imagine how shocking and disruptive it was when Paul told the church in Rome, “Live in harmony with one another. Do not be proud; instead, associate with the humble [tapeinos]. Do not be wise in your own estimation” (Romans 12:16).

There had to have been some jaws on the floor. I can picture people sliding out the door of that house church thinking, These people have lost their minds. Ain’t nobody got time for dat.

This isn’t the only time Paul said something like this. It was a consistent theme throughout his letters—he taught it to the churches in Rome, Corinth, Ephesus, Philippi, and Colossae.

When we came into Macedonia, we had no rest. Instead, we were troubled in every way: conflicts on the outside, fears within. But God, who comforts the downcast [tapeinos], comforted us by the arrival of Titus. (2 Corinthians 7:5–6)

I, the prisoner in the Lord, urge you to walk worthy of the calling you have received, with all humility [tapeinophrosynē] and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, making every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace. (Ephesians 4:1–3)

Do nothing out of selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility [tapeinophrosynē] consider others as more important than yourselves. Everyone should look not to his own interests, but rather to the interests of others. (Philippians 2:3–4)

As God’s chosen ones, holy and dearly loved, put on compassion, kindness, humility [tapeinophrosynē], gentleness, and patience. (Colossians 3:12)

He will transform the body of our humble [tapeinōseōs] condition into the likeness of his glorious body, by the power that enables him to subject everything to himself. (Philippians 3:21)

Over and over, Paul reiterated the importance of the humble life for the believer in Jesus.

When the people sitting in these churches first heard these words from Paul, they might have thought, Wait a minute. Did Paul really say the H– [I guess in Greek, the T-] word? He presented it as the identity-forming virtue that should mark Christians. What motivated Paul to make such a countercultural, even offensive, claim?

It’s actually pretty simple. He followed the Messiah, Jesus, who lived a countercultural life that was offensive to both the Romans and the religious elite.

Paul’s most striking use of humility might be in Philippians 2:8–9: “He [Jesus] humbled [tapeinōsen] himself by becoming obedient to the point of death—even to death on a cross. For this reason God highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name.”

Because we find ourselves “in Christ” (another favorite saying of Paul: Romans 8:1; 1 Corinthians 1:30; Galatians 2:16), it makes sense for us to identify ourselves with him in all things, especially in his humility. Why? Because the very thing that was true of Jesus will be true of us. Jesus humbled himself, and his humility led him through humiliation—but humiliation was not the end for him. As we’ve seen, humility was his path of exaltation.

This unity with him and shared exaltation with him is exactly what we just saw in Philippians 3:21: “He will transform the body of our humble condition into the likeness of his glorious body.”

What was true of Jesus will be true of us.

Adapted from The Hidden Peace: Finding True Security, Strength, and Confidence Through Humility by Joel Muddamalle. Click here to learn more about the book, and click here to learn more about the Bible study.

The peace we long for begins with coming to the end of ourselves.

There are inescapable aspects of life we are all marked by. We have less control than we want, more anxiety than we’re comfortable with and just enough insecurity to continually remind us of our shortcomings. To experience these things is to be human. We aren’t superheroes and invincibility isn’t an option.

But humility is.

Whether we’ve incorrectly defined it or underestimated its relevance to our daily life, humility is the missing piece for the security, strength and confidence we all want. It’s time to stop trying so hard to avoid our limitations or overcompensate for them. God has better for us and it begins with bowing low in humility.

With relatable stories, practical wisdom and biblical theology broken down into digestible takeaways, The Hidden Peace by Dr. Joel Muddamalle will help you:

Overcome the fear of being “found out” or looking like a fraud by realizing God’s intent for shortcomings and weaknesses.

Walk through hurtful situations in the most God-honoring way by gaining a true understanding of biblical humility.

Answer the question “why do bad things happen to good people?” by learning a perspective shift that will change how you process suffering.

Know confidently that you’re living with purpose and being used by God through seven ways to practically live like Him today.

Be led by the biblical definition of self-awareness so you can experience the unexpected ways it brings safety and security to your life.

Stop believing the lie that theology is out of touch or too difficult to comprehend as Joel shows you how to dig into scripture and study it yourself.

Weakness is not your enemy. Planted in the soil of humility, weakness becomes a means to gaining more strength and more peace.

Holding a PhD in Theology, Joel Muddamalle is the Director of Theology and Research at Proverbs 31 Ministries with Lysa TerKeurst and the theologian in residence for Haven Place Ministries, a ministry of Lysa’s that provides personalized theology and therapy retreats and smaller gathering. He also cohosts the popular podcast Therapy and Theology with Lysa and licensed counselor Jim Cress.

Joel serves on the preaching team at Transformation Church with Pastor Derwin Gray and is a frequent speaker for conferences and events (She Speaks, IF Gathering, Q Ideas NXT Gen Summit, Hope Heals Camp). One of his favorite things to do is leading in-depth theology workshops and training seminars for churches (FreshLife, Passion City, Transformation Church).

Joel coauthored 30 Days of Seeing Jesus Throughout the Bible and has had the honor of working with Christian authors in developing the theological framework of their books through COMPEL consulting.

Based in Charlotte, NC, Joel and his wife enjoy a full house with their four children and two dogs. If he doesn’t have a theology book in his hand, you can be sure he’s either coaching one of his kids in a sport, doing his best to keep up his hoops game on the basketball court, or getting roped into a reel by his wife (@almostindianwife).

The Hidden Peace is published by HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc., the parent company of Bible Gateway.

[1] Markus Barth, Helmut Blanke, and Astrid B. Beck, Colossians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 34B, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 343.

[2] H. H. Esser, s.v. “Ταπεινός,” in New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, ed. Lothar Coenen, Erich Beyreuther, and Hans Bietenhard (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1986), 260. A point of nuance: This is not to say that any form of modesty was absent in the Greco-Roman world or that the concept of “humility” was negative without exception. Of course there were exceptions, but they were infrequent and not normative. In other words, humility was not viewed as a virtue in the Greco-Roman world. Paul radically changed this concept when he connected it to what is possibly the most important virtue of the Christian life.

[3] John H. Elliott, 1 Peter: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 37B, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 605.

[4] Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, ed. Roy Joseph Deferrari, trans. Vernon J. Bourke, vol. 21, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1953), 7.14.

The post Redefining and Cultivating Christlike Humility Like Paul appeared first on Bible Gateway Blog.