From the time that Israel began its sojourn in Egypt until its liberation under Moses, although God’s Chosen People were not in the land that was their inheritance through Abraham, they seem to have experienced something of the blessing meant for man in the beginning, when God called Adam to be fruitful and multiply. Thanks to Joseph’s divine gifts and prudential judgment, Israel enjoyed special favor in Egypt, and they “multiplied and became so very numerous that the land was filled with them” (Ex 1:7). Indeed, during the time of Joseph’s ministry, it was the Egyptians who sold their land and made themselves Pharaoh’s slaves in order to escape the ravages of famine (Gen 47:19–21).

Then a new king arose in Egypt. This man knew nothing of Joseph, and he oppressed the Israelites, forcing them to build new garrisons using brick and mortar, the implements of Babel (Gen 11:3). But God heard the cry of His people. And when God sent Moses as an instrument of Israel’s deliverance from bondage in Egypt, Moses did not ask Pharaoh merely to let the people go. He asked rather that Israel be allowed to worship. The exchange between the prophet and the king set the stage for the drama of the heart that would play out between the Lord and His people down to our day:

Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh and said, “Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: Let my people go, that they may hold a feast for me in the wilderness.”

Pharaoh answered, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey him and let Israel go? I do not know the Lord, and I will not let Israel go.”

They replied, “The God of the Hebrews has come to meet us. Let us go a three days’ journey in the wilderness, that we may offer sacrifice to the Lord, our God, so that he does not strike us with the plague or the sword.”

The king of Egypt answered them, “Why, Moses and Aaron, do you make the people neglect their work? Off to your labors!”

(Ex 5:1–4)

Israel had prospered in Egypt. They had grown from a tribe to a vast assembly which would become a nation. Yet it was not for any greatness on their part that God desired to deliver them. Nor was God’s project simply to free the people for their own pursuits. They were instead the people whom God had called to be His own, the people who, since the time of Abraham, had established altars and offered sacrifice to God, the people through whom all the world would be called back to its original glory as the space in which worship is offered to God the Creator. Israel’s proper liberty was not freedom from bondage, but freedom for worship.

Pharaoh did not know the Lord. And, in Moses’ request that Israel be allowed to worship, Pharaoh saw only an admission of laziness. In his eyes, a desire to worship this nameless God could only be an attempt to escape from the labor that constituted the worship of Pharaoh. And so he redoubled the labors of the people, commanding that they fill the same quota of bricks but without being supplied the straw for the work. The Israelite taskmasters were beaten and complained to Pharaoh. When he refused to relent, the people complained to Moses, incensed that he, with his message from God, had made them odious to Pharaoh. And Moses cried out to God as well, praying for the people’s relief.

Thus the fundamental choice was set before Israel, one which would be brought into focus at the establishment of the covenant on Sinai: Would they serve Pharaoh, or would they serve God? Would they persist in fashioning bricks—the six-sided building blocks of Babel that would harden in the sun as did Pharaoh’s heart in the light of God’s will—or would they themselves become, in time, a living temple of the Lord?

The drama of this choice may feel far-off to those of us occupying the latter-day, Christ-haunted Western world. Especially in America, where the love of freedom remains keen and where, bureaucracy notwithstanding, our wills are mostly left unfettered, we little sense the intensity of Pharaoh’s hold over us. We imagine ourselves beholden to no one, completely open to the luxurious possibilities of modern existence. We little suspect that we ourselves have become as pharaohs, exercising a shrewd tyranny over our own hearts as we grow less and less free to worship God.

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from a chapter in Daniel Fitzpatrick’s Restoring the Lord’s Day, available from Sophia Institute Press.

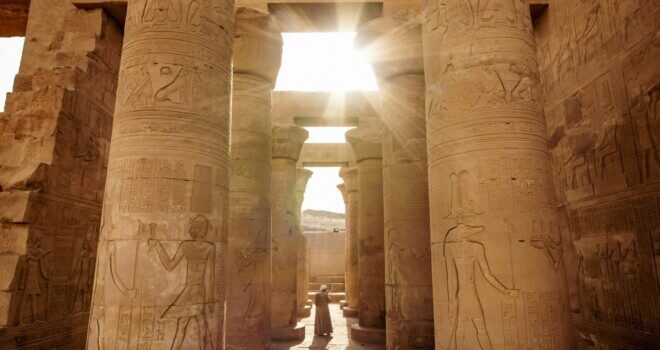

Photo by CALIN STAN on Unsplash