The Priest Who Took Down a Gang To Protect His Flock

In 1955, an American seminarian studying in Louvain, Belgium read a line from a poem that changed his life—and eventually the world.

The poem that jolted Venerable Aloysius Schwartz was “Still Falls the Rain,” by British poet Edith Sitwell, after a German air squadron’s bombardment in 1940. Sitwell depicts Christ nailed to the cross as a “Starved Man,” observing death in London’s fire-scorched streets.

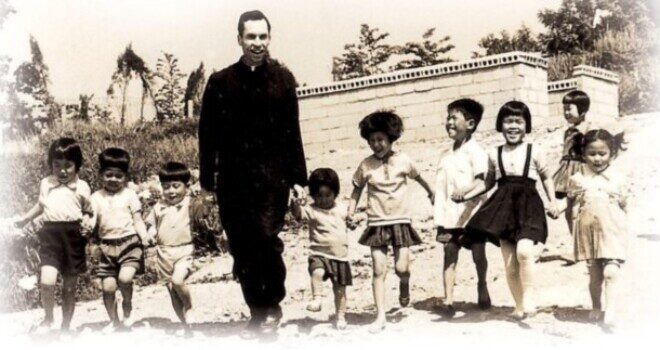

“Fr. Al,” who grew up poor in a Washington D.C. rowhouse during the Great Depression, began to understand his priestly identity as one of the “Starved Man,” taking on features of the world’s poor, humiliated, and abandoned. As Christ loved and became one with the poor, he would, too.

As his formation edged closer to his ordination, the idea of nailing himself to the Cross as the Starved Man, in persona Christi, gnawed at the seminarian. To serve Christ in total, Aloysius felt, he needed to embrace and live out Christ’s Passion.

When he was ordained in 1957, he visited an obscure apparition site in Banneux, Belgium, where he consecrated his priesthood to Our Lady, Virgin of the Poor. He asked Mary to fill his priesthood with the violence of her Son’s Passion.

Be careful of what you ask from the Mother of God.

As Fr. Al lay dying nearly forty years later, his body collapsing beneath the weight of ALS, he shared with those around his bedside his seminary zeal. Although he made light of Our Lady’s responsiveness, he said he wouldn’t have changed a thing. He intuited, in a supernatural dimension, that his willingness to live out Christ’s Passion perhaps saved the thousands of souls he brought into his Boystown and Girlstown communities throughout the world.

The alignment of Christ’s Passion with Fr. Al’s suffering is startling. Months before dying, he wrote of the similarities:

I am nailed to the cross of ALS. There are so many elements of ALS which remind you of the pain of Jesus nailed to the cross. … Jesus was totally disabled and immobilized. His hands and feet were rigidly fixed to the tree so that he could not move. My condition is now the same. I am totally disabled and can no longer move my hands or feet. On the cross, because of His position and the weight of His body, Jesus had great difficulty breathing. … He died of suffocation. … More than likely I will die of suffocation or choking…

Jesus experienced that overwhelming fatigue which comes from a lack of sleep. He had not slept the night before, and he had gone through terrible pain and torture. Because of the lack of oxygen and many other problems which cause insomnia, an ALS patient is always fatigued and experiences terrible sleepiness and drowsiness. Because of an inability to breathe, Jesus spoke very little from the cross. … Most ALS patients, when they die, have lost their ability to speak, not so much from a lack of oxygen as to the fact that their speaking muscles have atrophied. On the cross, Jesus did not eat or drink … ALS patients have enormous difficulty in swallowing anything, and as for myself the sight and thought of food repulses and even nauseates me. Also on Calvary, Jesus was stripped of his clothes. He was stripped of his human dignity and lifted up before the world as a spectacle and a laughingstock. I, too, have been stripped of my dignity. Each day is a fresh and new humiliation.

On Father’s Day weekend, it is well to remember this priest on the path to canonization, known throughout the world as a Father to the Poor. His willingness to take on suffering, peril, and assaults led to more than 175,000 Boystown and Girlstown high school graduates.

The following story tells the measures Fr. Al took to guard his spiritual children. This month, with the spread of the LGBT Movement, American clergy would be wise to note Fr. Al’s manner in confronting a strong-armed gang of teachers in the spring of 1990.

The two-month strike held outside the gate of his school in Manilla, Philippines began after Fr. Al terminated the contracts of five teachers who rejected Section #2357 of the Catechism, which clarifies the “intrinsic disorder” of homosexual acts. A few teachers told him that they would not leave homosexual lifestyles, nor instruct students on the virtue of chastity. “[They] wanted to take over the education program in order to remake the children into their own image and likeness,” Fr. Al wrote in his book, Killing Me Softly.

After Easter, he awakened each morning to brick- and rock-throwing protestors encamped outside the educational safe haven of 4,000 students. The gang barricaded food, drink, and supplies from passing through the entrance and often smashed the windshields of trucks attempting to bring food to the Sisters of Mary.

It was a bleak hour; Fr. Al had just been diagnosed with ALS and told that he had only a few years to live. On the Tuesday of that Holy Week, his body weakening, he fell and bloodied his face, blackening his eye. “In the depths of my heart,” he wrote. “I heard a voice saying that this was a warning of the great trial and crisis that lay ahead…however, my first duty was to the children.”

When one morning Fr. Al approached the striking teachers, he was encircled by gang members, who held signs calling the Sisters of Mary “tyrants,” “dictators,” and “fascists.” Fr. Al told them there was “no way he would give in.” The gang, though, was growing. They had begun to employ “professional strikers and goons.”

Once, when a handful of students mistakenly thought Fr. Al was grabbed by the throat by a protester, hundreds of teenage boys and girls poured out of buildings and raced to the entranceway “like a group of commandos storming the enemy,” wrote Fr. Al. “They began a counterattack.” Although the melee was quickly broken up, a newspaper carried a headline stating, “The Students of the Sisters of Mary Maul Striking Teachers.”

On Pentecost morning, provoked by the violence (a few young men under Fr. Al’s care had been beaten by metal pipes), Fr. Al spoke with the gang leader. “I told him that we would no longer tolerate their presence—that it was disruptive of our educational program and created an atmosphere of tension and anxiety which was very harmful to the children,” Fr Al wrote. “I mentioned that, if they continued, we would meet violence with violence.” The gang leader was rendered silent.

Fr. Al then informed him that he had assembled “his own gang,” approximately 8,000 Catholic fighters enraged about their attacks on the Sisters of Mary. His own “gang” would no longer tolerate the bullying of the Sisters and students. “From now on,” Fr Al told the leader, “you and your fellow strikers should sleep very lightly at night.”

Two days later, the gang disappeared. It was over.

Fr. Al was left shaken and physically wearied by the two-month standoff.

“It took a terrible toll on my health and after the strike was settled…I found myself in something of a physical tailspin,” Fr. Al wrote. “I called my doctor to describe my condition and symptoms. His advice was to prepare, as it was very possible that in three or four months, I would be gone.”

He died shortly thereafter, on March 16, 1992—a Father to the Poor.

Author’s Note: To learn more about Venerable Aloysius Schwartz’s work to educate and bring the teachings of Christ and the Catholic Church to the poor through the Sisters of Mary, please visit worldvillages.org.