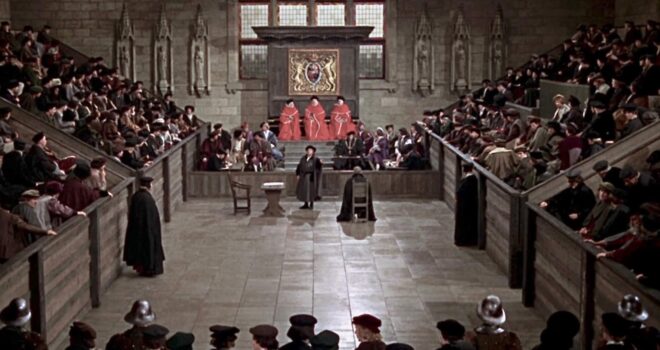

For decades, A Man for All Seasons has been considered one of the greatest Catholic films of all time. After all, here was a prestigious Hollywood film, a Best Picture winner no less, focusing on a Catholic saint, Thomas More. The main drama of the film centers around the saint’s fall from worldly honor and wealth due to his persistent clinging to his faith. It is no wonder that A Man for All Seasons regularly tops lists of best Catholic films and appeared on the Vatican’s list of great films published in 1995. More’s voice throughout is unapologetically and unmistakably Catholic, perhaps surprisingly so given the director, writer, and lead actor were Jewish, Communist, and Anglican. However, in recent years, this film and the play from which it was adapted has come under fire from Catholics who argue that Robert Bolt’s More does not reflect the Catholic saint but rather more contemporary concerns.

Reformation scholar Eamon Duffy sums up this argument in his 2021 book A People’s Tragedy:

Bolt’s More is not a martyr for religious truth but an icon for the age of dictators and the McCarthyite witch hunts, a twentieth-century liberal born before his time, dying in defense of the rights of the individual against a coercive regime. Bolt’s play and the film derived from it offered a seductive but radically misleading picture of More, as a liberal individualist concerned above all with personal integrity.

The More of A Man for All Seasons has consistently been interpreted as a liberal martyr for conscience ever since the film debuted, to the point where this interpretation started coloring the perception of the historical St. Thomas More, a man who had little tolerance for heresy even if deeply held by conscientious people.

But does the film really depict Thomas More as more devoted to conscience than truth? Is Bolt’s More little more than an avatar for Jeffersonian separation of church and state? Indeed not. The Thomas More of A Man for All Seasons is a man of great virtue, devotion to truth, and deep love for God. It is from this deep love that his conscience, and his identity, is formed, and it is his devotion to truth which drives his actions throughout the film.

Plenty of characters throughout A Man for All Seasons are preoccupied with conscience, but interestingly Thomas More is not one of them. He only utters the word “conscience” once when it has not already been said in the scene by someone else. Wolsey, Cromwell, Richard Rich, Henry VIII—all of More’s antagonists discuss conscience freely, but More rarely does. He seems to constantly prick the consciences of those around him, either by argument or by example, trying to bring them back into alignment with the truth. More reminds Wolsey, the corrupt and cynical churchman, of the power of prayer; he outright refuses to allow Will Roper to marry his daughter Meg because Roper is a heretic, and one who seems to be convinced by Luther in good conscience at that; he consistently opposes Henry VIII’s divorce, in council and in conversation, even though Henry’s conscience clearly tells him that his marriage to Queen Catherine is incestuous. More does not afford the same respect to the conscience of others that a true twentieth century liberal would; only if the conscience is aligned with the truth should it be respected.

More’s deepest allegiance is to God and to His truth; he defines himself by the love of God. While talking to his friend, the Duke of Norfolk, who is trying to convince More to give in to King Henry’s demands, More says “affection goes as deep in me as you, I think. But only God is love right through, and that’s my….self.” Rather than espousing some radically individualistic concept of self, More defines his very being by the all-penetrating love of God.

This line gives context to his oft-misunderstood line from an earlier conversation with Norfolk, who had asked why he was willing to give up his position as Chancellor of England for the “belief” of apostolic succession and papal supremacy: “because what matters is that I believe it, or rather no, not that I believe it but that I believe it. I trust I make myself obscure.” More’s sense of self, his sense of identity, is completely bound up with God’s love and truth. Therefore, it is his Faith, rather than his conscience, which governs his actions in this film. His faith in the truth of God and His church is his very self, and that is why he gives up his wealth and power, why he is willing to “stand fast a bit, even at the risk of becoming a hero.” This is the self to which he is stubbornly true, the personal integrity he dies to uphold. Thomas More, in the film as in real life, was not merely a martyr for conscience, but truly a martyr for Faith.

A Man for All Seasons deserves it place near the top of the list of great Catholic films. St. Thomas More’s many virtues, firm commitment to truth above all else, and deep love for God shine through every moment of this magnificent film. His example of courage, statesmanship, generosity and affection towards friends and dependents, steadfast faith, and love for God and family stand as noble models of Christian living. More’s faith and integrity, as much in the twenty-first century as the sixteenth, call us to hold steadfast to the truth no matter what the cost or how unreasonable the demands of the faith seem by worldly standards. After all, “finally, it is not a matter of reason,” as St. Thomas More tells his family while awaiting his trial, “it’s a matter of love.”

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from the author’s blog 100 Movies Every Catholic Should See.

Zinneman, F. (Director). (1966). A Man for All Seasons [Film]. Columbia Pictures.