When it comes right down to it, High Noon and another of director Frank Zinneman’s masterpieces, A Man for All Seasons, tell basically the same story. The protagonist of both films is a dedicated public servant who, shortly after resigning their office, must face a crisis of conscience, choosing to follow that conscience against the advice of friends and the pleading of family, and ultimately must be willing to lay down their very lives in service of a higher principle that seems like folly to all those around them. Deputy Marshal Harvey Pell is even basically Will Kane’s personal Richard Rich!

Okay, I admit, the analogy may be a little far-fetched. But I do find it interesting that Frank Zinneman directed two films in such disparate genres and yet managed to explore many of the same themes. And since A Man For All Seasons is arguably the greatest Catholic film of all time, High Noon is a true classic that every Catholic ought to consider seeing.

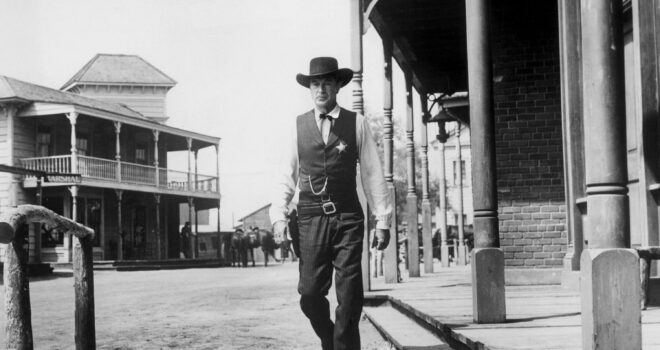

High Noon follows the story of US Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper), who is retiring in order to marry his Quaker sweetheart Amy (Grace Kelly). However, after the wedding, as he is about to ride off into the sunset, Kane gets a telegram telling him that notorious outlaw Frank Miller (Ian McDonald) has been released from jail and is on his way to town to get his revenge on Marshall Kane. Kane is torn on the one hand between his desire to leave with his new wife, a strict pacifist, and start his new life, and on the other hand his duty to protect the town and his knowledge that Miller will hunt him to the ends of the earth. Kane figures that it would be better to end the feud here than be looking over his shoulder all his life.

Amy, unfortunately, disagrees, and as Kane arms himself for battle she threatens to leave on the very same train that is bringing in Frank Miller. She is not the only one of Kane’s friends who abandons him in his hour of need. For one reason or another, the entire town has an excuse not to join Kane’s posse and stop Frank Miller and his gang. Some have grown old and can’t shoot straight anymore; some plead that they have a family and can’t risk leaving them orphaned; some believe that it would be better for the town if Kane fled and the final confrontation happened elsewhere. Some have even more devious reasons: people who prospered under Miller’s despotic rule in the town; some who hide from cowardice when Kane comes calling; even a deputy who is envious of Kane and angry that he was passed up for promotion to Marshall. As the clock ticks closer and closer to the arrival of the train at high noon, Kane goes from friend to friend asking for help, and at every turn his years of dedicated service are repaid with excuses and closed doors.

Will Kane must walk alone, taking the burden of the whole town on his shoulders and facing death on their behalf. As such, he joins the long tradition of cinematic Christ figures, going through his own Gethsemane where no one will watch one hour with him and finally confronting the forces of evil in his own sort of passion. Miller and three cronies walk into town hunting for Will Kane, and he engages them in a classic Hollywood gunfight. Outmatched from the very beginning, Kane must use his wits to slowly whittle down the opposing force and protect the town he loves. One person eventually stands with him, but he is essentially on his own through the entire conflict. His courage and sense of duty cause him to be willing to sacrifice himself for the sake of the town in the face of seemingly impossible odds.

Like all the best stories (and the story of Christ), High Noon has a eucatastrophe, a triumph of good over evil even after all seems lost. Will Kane defeats Frank Miller, saving the town which would not lift a finger to save itself. However, he has lost his respect and love for his former friends in the process and leaves town with his bride, dropping his marshal’s badge in the dirt as he goes. Frail and self-interested humanity was unable to step up and do the virtuous thing, even in the face of grave danger and the inspiration of a courageous man.

High Noon is simultaneously skeptical of human nature in general while showing the great potential for virtue in each individual man—something also seen in Zinneman’s A Man for All Seasons, which features many selfish and self-interested characters in contrast with St. Thomas More’s virtuous example. High Noon is an excellent exploration of similar themes of virtue, integrity, and sacrifice in the context of a different genre, making it another great cinematic classic worthy of watching time and time again.

Zinnemann, F. (Director). (1952). High Noon [Film]. Stanley Kramer Productions.