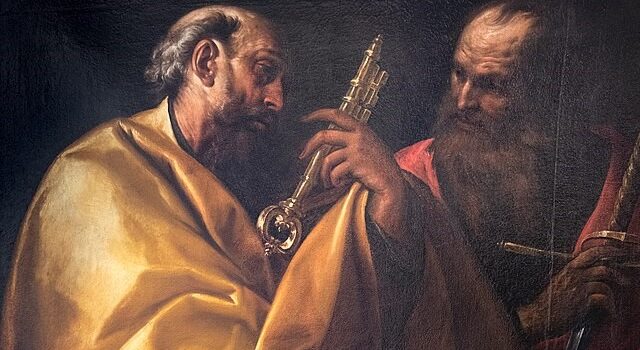

A Reflection for the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul

The joy of a good evangelist is infectious. Today’s greatest saints draw you into the beauty of the Catholic faith through their preaching—a holy priest who tells you truths you’ve never contemplated, a husband and wife who tend to the needs of their young family, the catechism teacher, a caretaker for the elderly—the list is infinite. Love disguised in words and actions are the tools that fix the world. And we who need fixing are like scrap metals attracted to the magnets of evangelists.

St. Paul was a spiritual magnet. Like Christ, the evangelist par excellence, Paul’s popularity spread throughout the world. He had something that people wanted to experience.

While in Athens, Paul’s preaching fell upon the ears of the pagan philosophical elite. These deep thinkers were enticed by his words—they made them think in ways they never had. They led him to the Areopagus, a center for philosophical dialogue among the cultural leaders of Greece, asking him, “May we learn what this new teaching is that you speak of? For you bring some strange notions to our ears, we should like to know what these things mean” (Acts 17:19-20).

St. Paul was primed to convert them. He had their attention. He had their interest. He had something that they wanted to experience more deeply. And while he stood in their courts explaining with perfect precision that the “unknown god” they worshiped upon their altars was the one, true God…

St. Paul failed.

He did not convert the Athenians.

Some scoffed at the Saint.

Others said they’d rather “hear him on this another time.”

Only a few became believers.

St. Paul preached a perfectly theological treatise. But he didn’t give them that something that the Athenians needed.

That something is the Cross.

It’s a homily that rarely is preached beyond Good Friday. It’s a mission that is seldomly completed. Few desire the Cross because the majority don’t know its secret power.

St. Paul continued his evangelistic mission into Corinth. There, he didn’t make the mistake of withholding the Cross. He writes:

for the word of the Cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God…it pleased God through the folly of what we preach to save those who believe. For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles. (1 Cor 1: 18-23)

The Cross makes Christians unique. The spirituality of suffering is that “strange notion” that the Athenians wanted—needed—to hear in order to complete their ancient understandings of the world. It is the missing piece to the human puzzle which was put together by the logic of spiritual, philosophical, psychological, and academic masters for centuries—all that we need for completion is to find meaning in our suffering.

The Cross is our secret weapon. It doesn’t operate in the same way as a sword or a pistol; it’s more like a key. It unlocks the gift of suffering, a paradoxical truth that inlays the spiritual realm within our current realities. St. Pope John Paul II wrote in his Apostolic Letter Salvifici Dolores that suffering is:

a universal theme that accompanies man at every point on earth: in a certain sense it co-exists with him in the world, and thus demands to be constantly reconsidered…It is as deep as man himself, precisely because it manifests in its own way that depth which is proper to man, and in its own way surpasses it. Suffering seems to belong to man’s transcendence: it is one of those points in which man is in a certain sense “destined” to go beyond himself, and he is called to this in a mysterious way. (SD, 2)

According to Aquinas, we are in movement constantly. Mentally, emotionally, and physically, our human bodies are on a roller coaster of sensations. We go from joyful to sorrowful depending on what life throws at us, but we undulate between these extremes for most of our lives. These movements have one of two endpoints: “to generation, which is a change ‘to being,’ and to corruption, which is a change ‘from being’” (ST. I-II Q. 23 A.2). Our passions then, be they worldly or heavenly, are the fires that burn within our souls. They can both enliven our lifeblood in God or cut us off from His life-giving vine. The human will is the fulcrum on which these two extremes balance—we can choose “to being” or to move away “from being” but, either way, we can expect to experience pain during our journey.

Suffering (or sorrow), then, becomes a gateway “to being.” St. Paul’s wrote, “At present we see indistinctly, as in a mirror, but then face to face. At present I know partially; then I shall know fully, as I am fully known” (1 Cor. 13:12). St. Peter similarly tells us that we are “being builtinto a spiritual house to be a holy priesthood to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ” (1 Pet. 2:5). Our movement “to being” is our transformation into Christ—to become “crucified in Him so that it is no longer I who lives, but Christ within me” (Gal. 2:19-20).

We do not yet know who we are until we experience suffering, for when we are stripped of our comforts, we strip away our very selves, erasing our hand-drawn silhouette from the canvas so that Jesus can paint it in perfect precision.

Sacrifices, pain, sorrow, suffering…these are the checkpoints on the “narrow road” upon which the Christian travels.

Our destination is Christ.

He who guided Paul and Peter guides us today to Paradise where all our sufferings will be as nothing compared to His eternal glory.

The key to unlocking those pearly gates is the Cross.

Crespi, G.B. (1628). Saints Peter and Paul [oil on canvas]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.