As we are reminded at the end of the pericope Luke 18:9-14, “for everyone who exalts himself shall be humbled, and he who humbles himself shall be exalted,” humility plays a central role in the interior life of a religious person.

The religion Christ describes is a living, interior religion, rooted in truth—truth about oneself, others, and God. While humility literally refers to the “ground” or “being grounded” (humus in Greek), it is truth that lies at the root of humility.

In his book The Shattering of Loneliness: On Christian Remembrance, Bishop Eric Varden, examines the etymology of the word “truth,” aletheia in Greek. More than just groundedness, aletheia refers to “a lucid clinging to memory and consciousness” (p. 113). To break the word down further, the river Lethe is the underground river of willful forgetfulness, where the shades drink to forget their past. Such forgetfulness has a type of culpability which creates a lethargic state of soul, a “morbid drowsiness” of sorts. Aletheia, therefore, requires this lucid clinging to memory in order to get away from Hades; it is “to come to the light” in the Spirit.

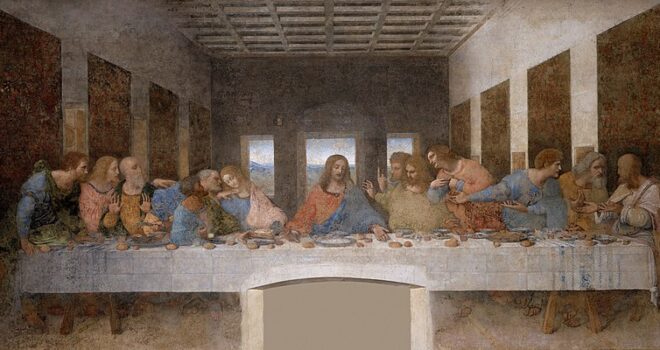

Such is the reason for the religious clinging to the Truth at the Mass. As Our Lord reminds the Apostles at the Last Supper, “Do this in remembrance of me” (Lk 22:19). It is a real memory that brings Christ to our present moment, to help us make sense of what we experience, to give us strength to confront our crosses with a more profound perspective.

Why is this particularly telling in our time? One cannot help but think of what happened at the 2024 Olympics in Paris. Notwithstanding their rewording of reality, what was seen by millions of people was a very blaspheme representation of the Last Supper, where Our Lord said, “Do this in remembrance of me.” To see this memory mocked at the Olympics with the pride that rejects what is Truth Himself makes one aware of how low we have come in our willful forgetfulness of the glorious past of Christendom. First, we have to be mocked during the Month of the Sacred Heart, a Human-Divine Heart filled with divine humility. Then, during the Month of the Precious Blood, we must be faced with a drunken god, Bacchus, and a transgender representation of Our Lord Himself. How far we have fallen.

In Progress and Religion, Christopher Dawson sheds light on three categories of cultural analysis: folk, work, and place. If the folk, i.e. the “quality of the population” is demoralized, everything falls. If the folk is reduced to a lethargic stupor which willingly forgets its Savior, then we cannot be surprised when destruction surrounds us. (Dawson, p. 62)

A return to Our Lord and to a life imbued with the impulsio Dei, the impulsion of God, the Love Who is the Holy Spirit, is what is necessary not only for a redemption but a recreation of man. In some ways, we are like the man beaten in the parable in Luke 10:23-27 who has to wait for the Good Samaritan not only to redeem him but to recreate him.

The Good Samaritan represents the one from the “outside.” The Levite and the priest represent natural philosophy and natural religion, respectively. However, a lesson to be learned from this parable is that if we merely work from within our system, we go nowhere. The system itself is blind and corrupt. Such is the state of original sin.

Grammar affords us the example of univocity and analogy. Univocity is to speak with “one voice,” the same language, the same “system” found within an environment. It could also refer to “monolingualism.” Analogy refers to different voices having similar meanings. To take the example further, people who only speak one language have only one vision of the world. Bishop Varden, in fact, cites Andrei Makine’s remark that monolingualism produces a totalitarian vision of the world. “This object is called a book and that’s it. Whereas the bilingual child, faced with one object with two names, will have to grapple with abstract and philosophical ideas early in life. He knows that no name is definitive” (cf. Varden, p. 148). In the same light, the Good Samaritan comes from without. Salvation, redemption, recreation necessarily come from without.

Bishop Varden offers some enlightening thoughts on these matters when he distinguishes between desire and longing. Looking at the Greek roots of these words, hedone and pothos, desire and longing fall into two different levels. Desire means to take pleasure or “to enjoy.” We see this with the “hedonist” whose life is governed by pleasure seeking. Longing, on the other hand, refers to a yearning for a lost or distant thing—a thing known and treasured but out of reach. Desire could be univocal, whereas longing could be analogical. Hedone (desire), therefore, issues from within, from one’s wish of satisfaction, while pothos (longing) is experienced by force of something outside of oneself (cf. Varden p. 146).

Varden comments, “Our time is wary of words. It shuns dogmas. Yet it knows the meaning of longing. It longs confusedly, without knowing what for. But the sense of harbouring a void that needs filling is there” (p. 155). These words highlight our paradoxical search for satisfaction within a corrupt system, when our longing itself confirms the presence of something “outward,” where our true satisfaction lies.

It is here that the bishop’s summary of the great work by St. Athanasius, De Incarnatione, is very important. God’s intervention in the Incarnation is one of recreation, not just redemption, because the problem crying out for a solution was not sin but death. Varden states:

Accounts could have been settled, we might say, on the basis of the existing economy, with no need for a new currency. The challenge facing God was another, namely that of freeing humankind once again, now in new circumstances, from its natural limitation…The divine image, made for immortality, lay in ruin. It could not just be glued back together. A new creation was called for. That is why the Logos entered history. (pp. 140-141)

Bishop Varden summarizes our condition very well:

Finding us forgetful, unaware of God’s image in ourselves, the Lord hoped the beauty of creation, his handiwork, might raise our minds. It was not enough. He sent us prophets. They were not much more effective. Man’s horizon had shrunk to such an extent that he moved as in a ditch. Although he confusedly sought God ‘in creation and sensible things,’ he no longer conceived of any reality beyond the phenomenal world. He was unaware of anything over and above what he could see and touch. (p. 143)

Such is the faithless world in which we live.

In many ways, today we are like the sophists, the nominalists, the rationalists, and existentialists who can no longer conceive of any reality beyond the phenomenal world. We need the Logos from outside of the phenomena we live in to give us meaning. It is for this reason that a contemplative life that lives considering the Eucharistic mandate “Do this in memory of me” is crucial not only to counter the current but to go beyond it, to recreate it. Some, like pagan alt-right Dominique Venner (1935-2013), oppose the system with a strong reaction, committing suicide in the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris while critiquing the Catholic Church for the mess in which we find ourselves. Others, like the Paris Olympics eleven years later, push the system forward, also critiquing the Catholic Church as they claim to be “woke.” Neither is right. A renewal of the system is necessary, and that renewal can only come from the Logos, speaking to us in and beyond history.

da Vinci, L. (1495-1498). The Last Supper [painting]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.