The Christian life is a life of grace. It draws us beyond the limits of our human nature and into the supernatural by sharing in God’s Trinitarian life. The only way for us to attain such a life is by God’s help, through His grace. On their own, our efforts are useless. We cannot overcome sin without God’s grace; we cannot achieve salvation without God’s grace. If grace is so critical, how do we get it?

God’s grace comes to us through Christ, who merited it for us. By His sacrifice on the Cross, Christ satisfied for our sins and merited infinite grace which He can bestow on us individually when we are united to Him, when we become members of His Body by entering the Church through Baptism.

This leads us to the sacraments. The seven sacraments which Christ instituted are tools by which He bestows the effects of His passion. In other words, they are the particular ways that Christ gives His grace to us. Thus, the sacraments are the concrete ways that we participate in Christ’s life and His sacrifice on the cross.

Baptism, since it is the sacrament which initially unites us to Christ and makes us members of His Body the Church, is the most necessary sacrament. Yet it is the Eucharist, the very same sacrifice on the cross, re-presented in an unbloody manner, which merited salvation and grace for us, that is the greatest sacrament. The Eucharist has a secondary primacy to it as well: we can receive it often. We are obliged to participate in the Mass at least weekly, but we can do so even daily (not just once in our lifetime, as with Baptism).

Attending Mass is not like attending a concert or a lecture. At Mass, we are not mere spectators. Instead, we participate in the sacrifice which is offered.

We do this in two ways. First, we give our consent to the sacrifice of Christ. Like Mary standing at the foot of the cross, we should consent to Christ’s self-gift to the Father. Mary stood on Calvary and approved of what her Son was doing. We kneel at church and do the same—the precise moment we give our consent is at the “Great Amen.” At that moment, the priest holds up the Body and Blood of Christ and offers them to God, praying, “Through Him, with Him, and in Him, O God almighty Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, all glory and honor is Yours, forever and ever.” We respond “Amen” to give our approval of glorifying God by Christ’s one sacrifice re-presented during the Mass. The “Him” that we pray through, with, and in is Christ.

The second way we participate in the sacrifice of the Mass is by uniting ourselves to Christ in His self-offering to God. We do not merely approve of Christ offering Himself to God, but we unite ourselves to Christ’s sacrifice. We join our own selves, our lives, all the good things we do and the evil things we endure to the sacrifice of the Cross and so offer them to God through, with, and in Christ. This also occurs at the moment of the “Great Amen.”

At this point a huge question arises. Why did Christ institute the sacraments? Meaning, why must we receive grace through the sacraments and not simply in private prayer? Why must we consent to Christ’s sacrifice and unite ourselves to it ritually at the Mass instead of at home when we read the Bible? Wouldn’t that have been simpler? Why bother with these ceremonies and liturgies?

The simple, and rather crass, answer is that it is because we are animals. Now, we are not merely animals, but we are animals—rational animals. We have bodies. We are not only spirit, like angels.

Our bodies are essential to our humanity. Because of our bodily nature, we learn through our senses. Further, we express ourselves bodily—this is a central part of John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, that “the body reveals the person.” Thus, it is natural for humans to use ritual and ceremony, utilizing the tangible to express the nontangible. Thus, when we worship God, we must do it ritually, liturgically, wherein physical signs express spiritual realities taking place.

Another example of the idea that since we are bodily creatures we must have ceremonies is contemporary secular “marriage.” Even in a society that allows divorce at any point for any reason (a society that does not value marriage or take it seriously), people still have extremely luxurious ceremonies to get married. These displays directly indicate the significance of ritual in human society, even apart from sacramental liturgy.

So, when we participate in the Mass, we are liturgically participating in Christ’s death on Calvary by consenting to His sacrifice and uniting ourselves to it.

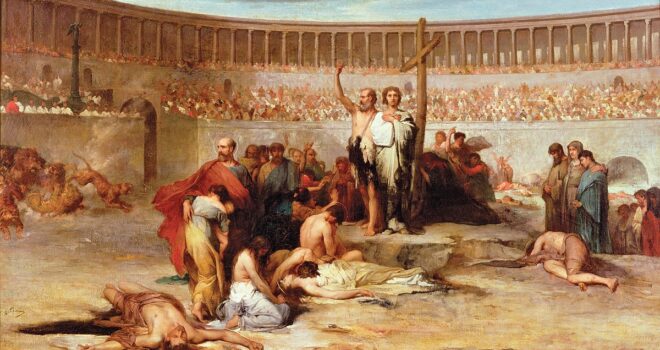

Martyrdom is a much more literal union with Christ’s sacrifice. While we at Mass do not die when we unite ourselves to Christ, the martyrs actually do die for Christ and with Christ. Their participation with His sacrifice is much more visceral. Thus, Christians have always recognized that martyrs enter immediately into heaven. (Purgatory is not necessary for them.)

Furthermore, the Church has always held that the martyrs merit grace for us. Their deaths, like the sacrificial death of Christ, are not merely meritorious for themselves but for us as well, meaning that we benefit spiritually from the sacrifice of the martyrs.

Martyrdom is Eucharistic in several senses. First, it is a great participation in the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross, like the Mass.

Second, Vatican II eloquently teaches us that the Mass is the source and summit of the Christian life. It is the source since we get the grace to live well from it, and it is the summit in that, as we have seen, it is at the Mass that we unite our whole lives to Christ. Martyrdom has a similar function within the Church. As we’ve mentioned, the sacrifice of martyrs benefits the whole Church with the grace merited by it (thereby serving as a “source” of grace). Additionally, the martyrs unite themselves wholly to Christ in body and soul when they make their paramount sacrifice (achieving the “summit” of union with Our Lord). The martyrs are thus seen as especially great saints within the heavenly ranks.

The earliest saints were the martyrs. It took several hundred years before the Church acknowledged any saint besides a martyr (and St. John the Apostle). To this day, martyrdom on its own is sufficient to get one beatified. Further, the martyrs drive the Church forward, as the ancient maxim goes, “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” The Pope used to wear red shoes, partially to signify the blood of the martyrs on which the Church flourished.

Third, there is no greater love than to lay down one’s life. Since we are embodied creatures, the greatest gift we can make to another is our very life. Dying for someone is the greatest single act of love we can make. Yet very few of us actually get to die for our loved ones. Instead, we dedicate our lives to their good and express this ritually (in weddings, the Mass, etc.). The martyrs truly lay down their lives. They get to express bodily their love for God directly.

Fourth, the Eucharist prepares us for martyrdom. To be a martyr requires great holiness and a zeal to give one’s life totally to and for God. The Eucharist is the main way by which we grow in holiness, in charity, and get to routinely offer ourselves and our whole lives to God, for His glory and not ours. Thus, the best way to prepare to be martyred is not through exercise and military training in enduring torture, but rather to participate devoutly at Mass.

In a world where martyrdom is not decreasing but increasing, and general persecution against Christianity is rising in the Western world, we must prepare ourselves for martyrdom as the early Christians did. One of the signs that the Church in America is not prepared to face persecution is that so many people do not believe in the Eucharist or do not value it properly.

Let us look to the martyrs, especially those who died for the sake of the Mass and the Eucharist, to strengthen our faith in and devotion to the greatest sacrament.

Author’s Note: This article was inspired by Fr. Francis Sofie’s book, Martyrs of the Eucharist, available from Tan Books. This book does the Church a great service by telling the stories of saints who were martyred for the sake of the Mass and the Eucharist. This shows us that, as great and noble as martyrdom is, the Eucharist is even greater—it is what many martyrs died for.

Thirion, E. (19th century). Triumph of Faith: Christian Martyrs in the Time of Nero [painting]. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.