Though it is a clear break between liturgical years and liturgical seasons as one crosses from the Feast of Christ the King to the beginning of Advent, I propose that a strong continuity between the two events can be found in the Catholic Old Testament, in 1 and 2 Maccabees.

I describe these two books as the most underrated of the entire bible for two reasons. First, they are criminally underread precisely because they are only found in Catholic and Orthodox Bibles. Leaving aside the tired cliche of Catholics not reading their bibles, there is also the fact that most of the English bibles produced are by non-Catholic publishers and for non-Catholic audiences. While the seven Deuterocanonical books, which includes 1 and 2 Maccabees, were initially included as an “apocrypha” at the end of the Old Testament in early Protestant bibles, this practice has largely been abandoned. One can still find this section in some Protestant academic or study bibles, but not in the bibles you will find in every hotel room.

Second, it is underrated because it is so good. It is a story with as much action, high drama, political intrigue, betrayal, and powerful dialogue as you will find in any Hollywood movie, with themes that resonate with Christians as much today as they did with the contemporary Jewish audience it shaped, including a contemporary Jewish audience that included Jesus and the Apostles.

The events of the books themselves only took place about 140 years before the birth of Jesus, making them about as close to His life as the American Civil War is to ours. The writing of the book is generally dated about 100 years before Jesus, which is about the same amount of time as we are to World War I and not much more distant than we are to World War II. Just as our country is still much shaped by the events of the American Civil War and the two World Wars, think how much more so the Maccabean Revolt would have been to Jesus and the Apostles.

The story of the Maccabees is a great story for the feast of Christ the King because it shows us who our true ruler and leader is. The Maccabees knew who their ruler was when the pagan Hellenist, General Antiochus Epiphanies, tried to force them to break their Jewish kosher laws. They knew who their ruler was when he tried to reconsecrate the Lord’s Temple to Zeus. The Maccabees even knew who their ruler was in the face of the corruption of their own religious authorities.

Now before you get the impression that this is all supposed to be a triumphalistic chest-thumping of Christian power over the rest of the world, remember what these stories included and the model of Christ’s kingship. If you want to know what boldness in the face of persecution looks like, read 2 Maccabees 7, and if you want to know what Christ’s kingship really looks like, reflect upon the icon, “Christ the Bridegroom” (pictured right). To take the posture of Christ the King is to take the posture of Christ Crucified.

Not only do the books of the Maccabees provide a model for us of faithfulness in the face of current trials, it points us in powerful ways to God’s ultimate plan, which we as Christians recognize as the Incarnation of His Son, Jesus Christ. It is common for Old Testament prophecies to not recognize the distinct aspects of the New Covenant explicitly but see them only in a hidden way. While other Old Testament books have foreshadowing of the Messiah, His divine nature, His sacrifice, or the Eucharist, Maccabees speaks in strong terms to the Jewish expectation of the resurrection of the body.

In the powerful scene of the martyrdom of the mother and her seven sons, what empower them all to face their torture and death is the promise of the resurrection. Who do these brothers cite as the one who will “raise” them up? He whom they call “the King of the Universe” (2 Mac 7:9). It is from him that they hope to receive again the hands they will lose (2 Mac 7:11). They expect God to “restore” them to life, even using the term “resurrection” to contrast their reward from that of their torturers (2 Mac 7:14).

We can see how much this affected the Jewish people of Jesus’s time through His conversation with Mary after the death of Lazarus. Jesus arrives to find His friend dead and is confronted by Mary who tells Him that His presence would have made a difference. Jesus tells her Lazarus will rise, and she confesses belief in “the resurrection on the last day” (John 11:24). The Jewish people, like Christians in Advent, had a hope and an expectation because of what had been set down previously in their Tradition. We can look forward to our own resurrection on the last day, especially because we have knowledge of the Resurrection of Jesus.

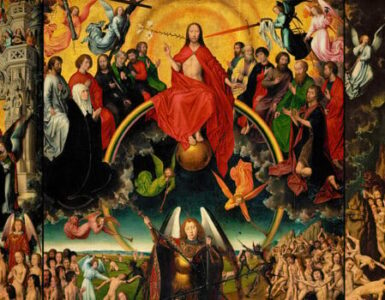

Advent is a season of expectation and preparation, first for the celebration of the initial coming of the Lord made known on Christmas Day, and second for the final coming of the Lord at the end of history. We are meant to see these things together, as St. Peter did when he said we are now living in “these last days” in Acts 2:17.

Jeremiah hid the Ark of the Lord “until God gathers his people again and shows his mercy” (2 Mac 2:7). The seven brothers and their mother offered their hands and tongues, knowing they would receive them back (2 Mac 7). We too are meant to prepare for the return of the Lord primarily by making an offering of our entire selves. This follows St. Paul’s charge that we “offer your bodies as a living sacrifice” (Rom 12:1) precisely because we are not conformed by “this age” but shaped by the age to come.

This age was anticipated by the prophets and the martyrs of Maccabees, but it was instituted by Christ the King. This Advent, we too become the harbingers of this same age.

Image from Wikimedia Commons